Kaiju Shakedown: Sammo Hung

Winners and Sinners

Sammo Hung is often called the greatest action director in the world. Why?

The backstory: Sammo went to a Peking Opera School called the Chinese Drama Academy as a child and his class spawned Jackie Chan, Yuen Biao (an acrobat considered the little brother of the group), Yuen Wah (who became Bruce Lee’s stunt double and a frequent onscreen villain), Corey Yuen (an award-winning director famous for working with women), and frequent action choreographers and actors, Yuen Miu and Yuen Tak.

The oldest in the group, Sammo was the first to get work as a stuntman and he took care of his crew, finding them jobs in the film industry. You can see a young Sammo fight Bruce Lee in the beginning of Enter the Dragon, and he’s directed Jackie Chan numerous times and is often employed to rescue or spice up a Chan production that’s gone off the rails (like Project A and Thunderbolt). While Jackie is referred to as “Big Brother” in Hong Kong, Sammo is called “Big Brother Big.”

Eastern Condors

Sammo’s career has had its ups and downs, but he’s worked with all of the most important action directors and artists of his day, including Jackie Chan, Tsui Hark, Donnie Yen, Jet Li, Lau Kar-leung, Angela Mao, and many, many more. Most of them talk about him with a reverence you reserve for God.

So what is it that he does? How does his action choreography work? To begin with, it’s important to know what he doesn’t do.

Before Sammo, Lau Kar-leung was the most important action director, virtually inventing the modern-day action movie. Lau is a walking encyclopedia of martial arts and his choreography shows off its different forms, problem-solving scenes by pitting one style against another. Lau shoots the full bodies of his combatants so that the audience can appreciate their skills. He often has his actors exchange 10 or even 15 movements in a single shot, and most of the energy in his scenes is generated by his actors moving inside the frame. The camera rarely moves, although Lau does sometimes pan or dolly around the outside of the “ring” formed by the action between his two fighters, putting the audience in the role of spectators. He also frequently uses a distinctive camera movement: a fast zoom-out, moving from a close-up of some hand or footwork to a full body shot.

By contrast, Jackie Chan choreographs to emphasize speed and dexterity. He prefers fistwork to footwork, often letting his fights sprawl all over the location, sometimes even moving between locations, and incorporating the environment into his choreography, breaking up his action scenes with small stunts, falls, and climbs.

Sammo directs with one concern: impact. Here’s how he gets it:

Framing and Tracking

Project A

Sammo hates “the ring.” He likes to puncture the space marked out by his two fighters, by sending his camera in close, circling them like Lau, then driving right through the middle of the fight. Changes in angle drive home the force and impact of blows, whether it’s a low-angle shot up through two fighter’s legs to catch their straining faces, or a high-angle shot to catch a tricky kick.

Because he’s more concerned with impact than speed, there’s less running in a fight scene by Sammo. Jackie Chan staged his final fight in Project A II to start in a soy sauce manufacturing plant before sprawling across the rooftops of an entire city. When Sammo staged the final fight for the first Project A, he set it in one room. The closest he’s come to Jackie’s style is the final fight scene in Millionaire’s Express that ranges across an entire Western town, but that one involves five different pairs of combatants rather than PAII, which simply focuses on Jackie.

Sammo’s use of single locations requires him to create a sense of movement within them, usually between just two fighters. One of his most famous techniques is the tracking shot that follow alongside his fighters as they battle, allowing them to move across the entire set, unleashing long strings of kicks and punches without exiting the frame or requiring a cut to another angle. The secret to these tracking shots is that they move in the direction of the fighter Sammo wants to portray as having the upper hand.

Sammo’s Dragons Forever, starring Jackie Chan, Yuen Biao, and the director himself, is a master class in this kind of framing. The final fight shows acrobatic Yuen Biao leaping and twisting around a high catwalk, switching between low angles and overhead shots to emphasize Yuen’s defiance of gravity. The last two combatants standing are Jackie and Benny “the Jet” Urquidez. During their fight, all the tracking shots move with Benny as he closes in on Jackie, pressing his advantage, refusing to give Chan room to breathe. It’s only in the middle of the fight when Jackie briefly rallies that we get a tracking shot moving in the other direction, from Jackie towards Benny.

Coupled with a shot of Benny punching directly into the camera lens, which leads to a shot of Jackie snapping his head back into frame, nose bleeding, the sequence gives the audience the impression that they’re under constant, relentless attack by Urquidez, putting them on Jackie’s side and making “The Jet’s” ultimate defeat all the more satisfying.

Speed and Slow Motion

Heart of Dragon

Lau Kar-leung has his fighters exchange 10 to 15 blows in one shot to show off their skill, but Sammo wants each move to hit home. So he often cuts on the movement, breaking a single blow and its reaction into four or five different shots. He’s a big fan of showing a punch or kick land in one shot, then cutting to another angle to show the reaction to the impact—an effect that is so fast the change in angle is almost subliminal. Sometimes he’ll have a blow land off-camera and show the character stumbling into frame before the audience can identify who hit him or her.

In his Jackie Chan film Heart of Dragon, there’s a one-minute-and-16-second fight inside a methadone clinic (available only on the Japanese DVD) in which Jackie takes on some criminals who have disguised themselves as doctors. In less than two minutes, Sammo cuts 44 times—one edit every 1.7 seconds. Almost every cut occurs on a movement with, say, Jackie spinning off the side of the frame in one shot, and spinning into frame in the next, creating what feels like a seamless blur of motion. Eight times, he splits a punch or kick and its impact into two or even three shots.

But that’s not his only trick. Take an earlier fight in the film, this one set in a parking lot between a gang and a bunch of cops, it’s a slower scene (2 minutes, 18 seconds) with only 50 edits, so one every 2.7 seconds. Sometimes Sammo lets his fighters exchange up to seven blows within one shot, sometimes less than one, and he unleashes his second favorite trick: slow motion. Often Sammo will put a punctuation mark on a fight by ending a furious exchange with a body sailing through the air and crashing to the ground in slow motion. In this parking lot fight, Jackie, after exchanging a dizzying number of blows with the leader of the gang, takes him down with a kick that is extended over four individual slow motion shots, all from different angles.

To see how this all comes together, check out the fight between Yuen Biao and Yasuaki Kurata at the climax of Sammo’s Vietnam War movie, Eastern Condors. The battle is fast and furious, lasting only 18 seconds, and divided into 13 shots (two of which are in slow motion).

1) Yasuaki Kurata has just shot another good guy, Lam Ching-ying, in the center of frame. Suddenly, Yuen Biao leaps into the foreground of the frame and begins a spinning kick.

2) The kick connects with Yasuaki Kurata’s face and he spins into the camera, which is behind him.

3) The camera now breaks the 180-degree rule, and is behind Yuen Biao, tracking with him along the ground, as he lands from his kick, rolls, and rises to deliver another blow as Yasuaki Kurata raises his pistol…

4) …and Yuen Biao grabs his forearm with both hands.

5) The camera is above the two combatants, looking straight down as Yuen Biao thrusts Yasuaki Kurata’s pistol into the air, its muzzle pointed at the camera lens, and it fires twice.

6) There’s a low-angle close-up of the two men from the waist down as Yasuaki Kurata tries a kick which Yuen Biao blocks with his knee.

7) Yuen Biao spreads Yasuaki Kurata’s arms apart and…

8) …we return to the #5 overhead shot as Yuen Biao delivers a kick that is almost entirely vertical, taking Yasuaki Kurata in the jaw.

9) Reproducing the set-up of shot #1, we see Yasuaki Kurata fly into the air in slow motion and hit the ground hard, reproducing almost exactly the same framing as when he shot Lam Ching-ying, only now it’s Yasuaki Kurata on the ground, and Yuen Biao standing over him. It’s the first moment in this fight that doesn’t feature contact between the two combatants.

10) A close-up of Yasuaki Kurata grabbing his jaw and rubbing it in pain.

11) An extremely brief close-up of Yuen Biao as he runs out of frame, moving left to right, restarting his attack.

12) The camera is behind Yasuaki Kurata, who is now standing, but it’s tracking towards him as Yuen Biao delivers two spinning kicks. The camera is moving with Yuen Biao’s direction of travel, emphasizing the speed and power of his kicks.

13) A close-up on Yuen Biao watching Yasuaki Kurata hit the floor. Then his head whips to the left as he spots a new fighter approaching.

Cutting on the movement, tracking shots, low angles, high angles, and slow motion—all are here, used in the service of turning an 18-second series of blows into a scene that conveys the anger and fury of Yuen Biao toward Yasuaki Kurata who’s just murdered his friend.

Repetition and Mirroring

Eastern Condors

Sammo has choreographed serious fights and comic fights, but except for their music there’s not a lot of difference between them. The humor in Sammo’s movies often appears when reality enters the frame, such as a character striking complicated martial arts poses only to be deflated by a wisecrack from his opponent. He likes to show that punches hurt, with his characters often pausing to lose their game faces as they react to the pain of a previous blow.

Most famously, this happens during the intense finale of Eastern Condors when Yuen Wah delivers a savage kick to Yuen Biao that sends him sprawling to the floor. Sammo joins him and Yuen Biao stands up to confront Yuen Wah, shoulder to shoulder with Sammo, striking a macho pose, ready to fight again before instantly passing out. Sammo uses almost the exact same trick in Dragons Forever after Benny “the Jet” Urquidez dispatches Yuen with one kick, but in this case, Yuen gives a wan thumbs-up before hitting the floor.

Sammo loves repetition, often having a character deliver a kick that misses followed almost immediately by one that lands hard. It’s a trick Jackie Chan picked up from Sammo that you can see most clearly in the final fight of Who Am I? as Jackie and another fighter kick each other savagely in the shins for almost thirty seconds then, as per Sammo, both fighters back off, rubbing their shins and grimacing in agony.

There’s also doubling. Sammo likes to draw parallels between his two fighters, having them do the exact same thing at the exact same time. In Project A, Jackie and Yuen Biao are in a bar brawl and they smash each other in the back with chairs, then they manfully back away until they’re hidden from sight before grimacing and writhing in pain. Or, at the end of Dragons Forever, Benny and Jackie both loosen their ties at the same time as they size each other up before they fight.

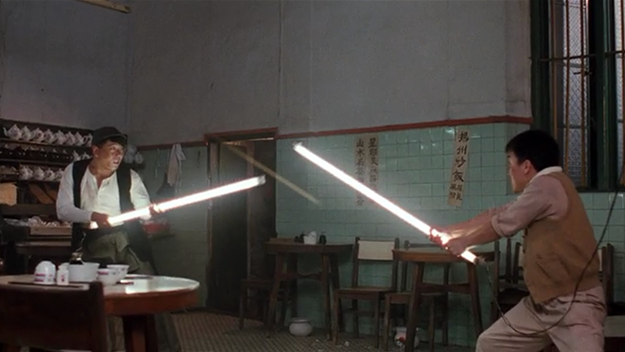

Pedicab Driver

To see all of this in action, and get how Sammo took what he learned from Lau Kar-leung and built his own style, you only have to take a look at the fight between Lau and Sammo in the middle of Sammo’s Pedicab Driver. In the movie, Sammo is on the run when he crashes into a billiard parlor and ruins Lau’s game. Lau challenges him to a fight.

The fight begins with Lau striking a classic martial arts pose and Sammo mocking it. Throughout the fight Sammo is rude and disrespectful and then Lau joins in, adding trash talk to their combat. The fight opens with a tracking shot as Sammo sucker punches Lau, then the tracking shot moves with him as the two men unleash 10 blows in the shot before Lau hits Sammo so hard the camera has to pan with him across the room as he staggers backwards.

Throughout the fight, there are exchanges of five or six blows in each shot, which is a lot for Sammo but not so many for Lau, and the sequences are broken up by humorous moments as one of the men pauses so his opponent can recover, or waits for the other man to get up, or puts away his cigarettes. Camera angles are low and high, with feet and fists coming directly towards the lens, to involve the audience. There are three slow motion shots, which is a lot for Lau.

Pedicab Driver

When action stars meet up onscreen, there are delicate negotiations behind the scenes revolving around who’s going to beat whom. For Lau and Sammo, their egos couldn’t have been more fragile. At the time, Lau was a living legend whose career was on ice, and Sammo was a huge young star just coming off some expensive underperformers. There’s no reason for this fight to even be in the movie as it’s nothing but a narrative digression that never pays off and is never even referred to again. Even Sammo says today that he wishes there were less random action scenes in Pedicab Driver, probably referring to this one.

But I’d like to think that this is a scene Sammo dreamed of putting in a movie for a long time to show the transition from Lau Kar-leung’s groundbreaking but old-fashioned style to Sammo’s more modern action sensibility that built on what Lau had pioneered. The result is a perfect combination of both styles. Lau shows off his mastery of different martial arts schools and has poise and gravitas, while Sammo’s camera movement and framing emphasizes impact, and his on-screen attitude plays up his image as the brash young Turk who likes to break the rules.

In the end, Sammo loses, but Lau congratulates him. “Fatty,” he says. “I’ve fought with many men. You’re the only one who scared me.”

And so the mantle is passed, from the man who was the first “greatest action choreographer in the world,” to the only man who proved he was worthy to inherit the title.

Grady Hendrix is a novelist and one of the founders of the New York Asian Film Festival. He writes on Asian film for Variety, Sight & Sound, and more.