Kaiju Shakedown: Michael Jai White

Jackie Chan doesn’t start to choreograph an action scene until he arrives on set, and then he’s been known to spend weeks putting the sequence together on location while the camera crew stands around waiting. Sammo Hung often does the same. Yuen Wo-ping spent almost a month on location putting together the final action scene of Once Upon a Time in China with Jet Li. It’s a truth that’s constantly repeated: if you want to make an action scene look good, you need time.

So it comes as a surprise to speak to Michael Jai White, one of American action cinema’s biggest talents. He shot his fight scene in Skin Trade (14) with Tony Jaa in one day.

“That whole interior piece we might have created in 10 minutes,” he says, talking about a 22-second sequence utilizing one long tracking shot and a few other quick angles. “Everybody just left us alone and we ran in there and practiced that stuff. We explained what we’d do without really doing it. He would say, ‘I’ll run across there,’ and I’d say, ‘I’ll kick the bookcase down, just avoid that.’”

While Jackie Chan could shoot close to 1,000 takes to get a shot right in Young Master (80), Michael Jai White makes it up as he goes along. But more and more, the speed at which White shoots his action scenes is becoming a trademark of his work, and it’s emerging as a house style for many American action movies, exchanging elaborate choreography for a rough-and-ready, vital, raw, and realistic frission.

Never Back Down: No Surrender

In White’s latest, Never Back Down: No Surrender, which he directed and starred in, he has a long beatdown in the ring with former UFC Heavyweight Champion, Josh Barnett.

“There are certain points when Josh Barnett and I are sparring. And we’re just sparring! The audience doesn’t know what’s going to happen because we don’t know what’s going to happen,” White said. “It’s just free-flowing, even though that’s kind of crazy — to be sparring with the most decorated MMA heavyweight in history and being the director of the movie at the same time.”

On White’s Blood and Bone and Undisputed II: Last Man Standing, speed was of the essence because budgets were low and time was tight. At times he’d shoot two or three fights in a day. But even when he does get time to rehearse, as in Never Back Down, White moves fast.

“Jeeja Yanin’s technique is so clean,” he says, talking about Thailand’s female action star who also appears in the film. “She had a scene with Brahim [Achabbakhe] who’s a top notch-stunt guy, that’s probably the fastest scene we shot in the whole movie. Probably an hour-and-a-half total.”

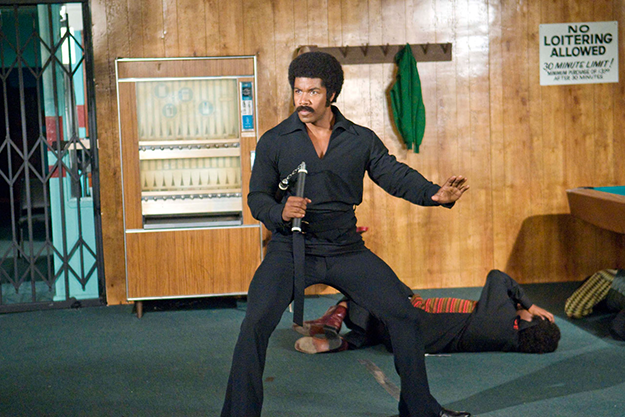

Black Dynamite

White is one of the few stars on the DTV (direct-to-video) action scene with major mainstream recognition, mostly due to the fact that outside his martial arts training he’s also done everything from play the titular role in Spawn (97), to recurring roles in Tyler Perry movies, to small parts in flicks like The Dark Knight as well as bigger ones in movies like Black Dynamite, not to mention TV roles in everything from Arrow to Mortal Kombat: Legacy and the Mainland Chinese series, The Legend of Bruce Lee (08).

His action work has mostly taken place in the DTV realm where the style of American action choreography is shaped in large part by the constraints of short schedules and tight budgets.

“I’ve done a few of the Hong Kong–style movies before,” White said. “Which is a luxury. They only do a few techniques in each take. That’s hard to justify with an American-based film crew. Every time we start shooting, we’re racing against the clock.”

That race against time kept American action choreography subpar for decades. But then technology changed. First, thanks to the VCR and DVD player, actors and directors and choreographers started seeing exactly what folks in Hong Kong were doing, and they wanted to do it too. Then cameras got lighter, more mobile, and more light-sensitive. As fewer lights were necessary and film stock got less expensive, and eventually disappeared altogether, every set-up got shorter, cheaper, and faster. Suddenly, searching for spontaneity was viable.

Never Back Down: No Surrender

“I want to get closer to real fights,” White says. “I think the three best fight scenes ever to me are Jackie Chan and Benny “the Jet” Urquidez in Wheels on Meals, Chuck Norris and Bruce Lee in The Way of the Dragon, and SPL with Donnie Yen and Wu Jing. That’s the direction I want to go. I want to choreograph mistakes. Just like in a great dramatic scene, I want people to believe they’re watching a real fight scene. I want to get further and further away from cliché.”

White pre-visualizes his action scenes, often shooting them on his cell phone to troubleshoot them and get them right. But spontaneity is key, just as in dramatic acting: “When you’re free to be in the moment, other things come to light.”

Technical factors play a huge role when you’re shooting this fast, and that comes down to the cinematographer and the editor. In Never Back Down: No Surrender White was able to shoot so quickly because he was working with a fight DP who “understands the language fully.”

“I had one of the greatest fight DPs — Ross Clarkson. He’s part of the choreography. I could do a few techniques and the next angle will work only if he moves the camera a certain way.” But he avoids camera tricks to sell impact. “If there were camera tricks you’d miss Fred Astaire’s art. If you saw camera tricks you wouldn’t appreciate Bruce Lee’s movement.”

It’s a version of KISS: Keep It Simple, Stupid.

“One of my most successful films is Blood and Bone,” he says. “The DP never shot action before, therefore there was a majority of action that was just done in the frame — he was resistant to moving the camera and that was a little problem. But ultimately we shot that movie very much like the old days, the way Bruce would have shot it. He just pointed the camera at me and let me do my thing.”

At the same time, you can see what a more experienced director, DP, and editor can bring to the table without going overboard in this clip from Undisputed II: Last Man Standing.

The camera is closer to the combatants, it sells the impact, and rarely shows them from the less dynamic angles of the Blood and Bone sequence above. It sounds easy, but a more traditional American approach using master shots and close-ups that values getting lots of coverage of the action from every single angle, can actually be a liability, in White’s view.

“Especially in the United States where people were mediocre in their movement, if someone didn’t move particularly fast you cut into the action. You didn’t show the kick from start to finish. They begin the kick, you shoot over their shoulder, and cut out a bunch of frames to make the kick land faster. That became the language of American fight scenes. That’s the fight I continue to have with people who’ve edited fight scenes but haven’t done it with someone who knows the art.”

When a cinematographer gets the approach, the footage will be “idiot-proof” for the editor, White says: “He doesn’t have that close shot of the foot to use that’ll tear apart the flow of the action. You don’t give them enough rope to get yourself hung with.”

The style emerging in the DTV market with White also includes actors like Scott Adkins who’s a trained martial artist and directors like Roel Reiné (Hard Target 2, Admiral) and Isaac Florentine. But this style is almost totally absent in big-budget Hollywood films, save for the few films that involve talents like Dan Bradley, the second-unit director whose fast, improvisational style gave the Bourne films their adrenalized chase sequences—and whose touch is sorely missed in the latest Bourne iteration.

“I feel like American movies haven’t even caught up with what the rest of the world is doing,” White said.

The changes White and others are introducing have closely tracked what technology has allowed. But right now, like John Henry beating the steam engine, these men are moving faster than the machines.

SIDEBAR: DTV x 3

Three other forces on the frontiers of action filmmaking.

Close Range

Isaac Florentine: An Israeli director living in America, Florentine shot second unit on Mighty Morphin Power Rangers for something like 60 episodes before he directed Desert Kickboxer (92) which started him climbing the ladder of DTV action movies. Now he’s one of the most talented action directors in the United States, despite the fact that his movies rarely play theaters. Shooting long takes and intense action, he’s helmed home video hits like US Seals II (01), Undisputed II: Last Man Standing (06), Ninja (09), Ninja: Shadow of a Tear (13), and Close Range (15). He frequently works with DTV action star, Scott Adkins, and, just as crucially, editor Irit Raz.

Never Back Down 2: The Beatdown

Larnell Stovall: A hardworking stuntman from Louisiana until 2007 when he choreographed, directed, and starred in a self-produced short film, Steel, which won awards and caught the attention of various action choreographers, Stovall has become one of the most innovative action directors in Hollywood. From DTV fare like Undisputed III: Redemption (10) and Never Back Down 2: The Beatdown (11) he’s moved up to choreographing action for the Ice Cube/Kevin Hart vehicle Ride Along (14) and second unit work on Creed. Currently he’s a member of leading stunt outfit 87Eleven, which White calls “the dream team of martial arts and stuntwork in the United States.”

The Expendables II

Ross Clarkson: an Australian camera operator who, like Christopher Doyle, moved to Hong Kong and got his big break with a name-brand Chinese director: in Clarkson’s case, Ringo Lam. He started out shooting the underwater sequences in Full Alert (97) before shooting four other features for Lam. Since then, he’s shot numerous Isaac Florentine films (Undisputed II: Last Man Standing, Ninja) as well as working on Conan the Barbarian (11) and The Expendables II (12), sometimes as camera operator and sometimes as the cinematographer on the second unit responsible for action scenes.

Grady Hendrix is a novelist and one of the founders of the New York Asian Film Festival. He writes on Asian film for Variety, Sight & Sound, and more.