Interview: Yann Gonzalez

With a title akin to a vintage 4AD album and promotional materials resembling some lost, neon-streaked urban noir, French filmmaker Yann Gonzalez’s Knife + Heart was a wild card in the 2018 Cannes competition. Occupying a space in the official selection recently reserved for such feverish, polarizing genre excursions as The Neon Demon (2016) and Double Lover (2017), Gonzalez’s second feature following the 2013 Critics’ Week discovery You and the Night provided the festival its requisite share of lurid thrills and erotic energy, managing, unlike many of its contemporaries, to lace its hedonistic, eye-popping pleasures with darker undercurrents. And now, just a couple of weeks before the film’s release in France, Gonzalez has been awarded the Prix Jean Vigo (a prize shared with Jean-Bernard Marlin, director of 2018 Critics’ Week selection Shéhérazade).

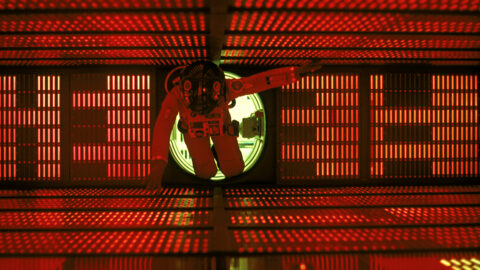

Set in 1979 on the eve of the AIDS epidemic, Knife + Heart follows Anne (Vanessa Paradis), a gay porn producer whose alcoholism has derailed her relationship with her girlfriend and longtime editor Loïs (Kate Moran), whose stability and support has helped her partner expand the creative potential of the adult entertainment industry. But when multiple members of Anne’s motley crew of hairy-chested, oiled-up actors begin to fall prey to a mysterious masked murderer—face obscured by Grand Guignol getup and armed with a switchblade dildo (because why not)—Anne is forced to trace the trail of bodies from the city to the countryside, where past transgressions and repressed memories obscure ever more dire secrets. Dripping with the stylistic residue of the era’s B-thrillers, and soundtracked by a lush, synthetic score by the director’s brother (aka electronic producer M83), Knife + Heart re-creates a period of sexual freedom and optimism that, like its subjects, was under nascent threat by unseen forces that would soon do irreparable damage.

Shortly after Knife + Heart premiered at Cannes, Gonzalez spoke with Film Comment about his film’s influences and its personal and logistical nuances. The interview took place in an appropriately ornamented hotel lounge, whose velvet carpeting, floral wallpaper, and mirrored surfaces seemed rescued from one of Brian De Palma’s visions of Reagan-era erotica.

Yann Gonzalez

I get the feeling when watching your films that your sets are probably pretty fun places to be.

For me, being on the set as a filmmaker is not really fun. It’s a lot of fears. But I’m someone who’s super-anxious and full of fears all the time. Every day of shooting I have stomach pains when I wake up because you have to focus on so many things all the time. But with this bunch of actors I worked with and the crew, it was like heaven on earth. It healed the pain in a way. It was full of laughter the whole time. Everybody was inventing something all the time. I like as a filmmaker to create a framework when I’m working on a film, and inside this framework, all the people that are working are free to invent, to offer suggestions, and to move freely.

What drew you to this era of gay porn?

Those are years that I’ve always fantasized about because I was born in 1977, so of course I was not a direct witness. But those were years of an incredible freedom where filmmakers feared nothing and there were no taboos. As a child and then as a teenager, with the technological possibilities afforded by VHS, I grew up watching films by Brian De Palma, Dario Argento, and John Landis. And those are very subversive films—the eroticism in them makes a very strong impression upon a kid. What I liked in those films was the idea of the obsession—that was the thin line that united them all.

The opening scene of Knife + Heart is especially reminiscent of De Palma. I was also reminded of the middle section of Boogie Nights, which deals with the transition of porn from film into the VHS era.

That’ll be the sequel. [Laughs]

Your films are very fantastical on the surface, but they also feel quite personal. When beginning a project, do you start with a theme or concept and build outward, or are you looking to explore certain types of characters or archetypes?

It depends on the film. For this specific one, everything started with the main character. I was inspired by a real female producer of the ’70s: she was an alcoholic, super-violent, and humiliated her actors. But at one point I thought it was a bit too sordid, so I turned this character into someone more glamorous, more romantic, a woman in love. But I kept the idea of a relationship because in real life she had a relationship with her editor, and I loved this idea of love transmitted by the images, by cinema, and contaminating the images themselves.

Did you envision Vanessa Paradis in this role from the beginning? I’m curious what she brought or added to the character.

She added everything. She built it in a way. She has such an iconic face, a very cinematic face. She reminds me of silent-movie stars. It’s funny because I watched the David Robert Mitchell film [Under the Silver Lake] two days ago, which talks about Janet Gaynor, and Vanessa really reminds me of Janet Gaynor. She has this childish face, very intense, full of emotions, and the way she appears in front of a camera, there’s always something happening, something surprising, something intense, something very moving. There are so many emotions in her.

Knife + Heart

This is a movie in love with movies and moviemaking. You shot on 35mm, and re-created a lot of porn films from the era. How important was it to properly reflect the medium and this genre, while keeping it fun and focused?

When I started the film, I thought this was going to be the last film of mine that would be able to use all the machinery connected to shooting on film stock. I wanted everything to be absolutely organic and in tune and in line with the practical facts and craftsmanship of shooting on film, which is something that is disappearing. Part of it was shot on 16mm, a format that is completely out of fashion nowadays. There is a physicality in working with film stock that somehow mirrors also the physicality and the physical expression of the protagonist. She tends to be very physical in expressing her feelings and her love. She has a sensuality that is somehow echoed in the matter of the film stock, the grain of the image, that kind of physicality.

So the re-created porn films were shot on 16mm?

Yeah. No digital effects. Nothing is fake. Everything is true.

What was it like re-creating them?

It was joyful but at the same time stressful because my crew were struggling to find the right practical elements [to properly re-create the films]. The editing table, for instance, arrived maybe two days before shooting began. One time a piece of equipment broke so we had to find the right elements in a northern part of Paris and bring them back to make the machine work. These are skills and crafts that have been lost with the advent of digital technology and we really felt like archaeologists, you know, trying to trace back not only the equipment but also the gestures that are connected to the fact of using that specific equipment and machinery. The colors, the shapes—it had to be precise. I also wanted to be very precise in the depiction of this woman editor at work. Kate Moran, the actress who plays Loïs, the editor, had training on 16mm. She actually edited her own short porn film—she had a lot of fun doing that. [Laughs] She worked with an experimental filmmaker who works on 16mm.

I imagine there was also an effort to lovingly represent what was the last gasp before the AIDS crisis.

Completely. I think there was a hedonism at the time that we completely lost during the ’80s and the rise of AIDS. And I wanted to portray that, to depict some characters, some free-spirited characters with no barriers, with no taboos. There is an attitude in those protagonists of the ’70s—in the faces, in the bodies, you see in those porn films that they enjoy giving mutual pleasure to one another. There’s an innocence, a naïveté, in those films. They were the pioneers of the porno genre in a way because those were the very first porno images and there was a joy in the fact of pioneering a movement, of making joyful love, having sex in front of a camera.

Actually, two years ago I had carte blanche at the French Cinémathèque and I made a 16mm print of a French porno from the ’70s that to me is a masterpiece. It’s called Équation à un inconnu. I don’t know how you translate that to English: “Equation to the unknown”? It’s such a melancholic movie, there’s so many mise en scène ideas and the cinematography is amazing. It’s one of the most poetic films I’ve ever seen. To me, it was such an emotional moment—I was very proud to be able to take this film out of darkness, a film that was hidden somewhere. I discovered it by watching a VHS—the image was awful, as you can imagine—but then I found that there was a negative in a lab and I decided to pay with my own money for a 16mm print in order to be able to screen it at the Cinémathèque. All the people there were absolutely hypnotized.

Knife + Heart

How do you balance these poetic and personal aspects with the more fantastical and artificial elements of your films?

When I make a film, I always have the impression that there is a duel between me, a film buff, and me, the filmmaker—or between the cinephile and the filmmaker. I think that the images usually reflect my cinephile or cinematic unconscious at work, while the dialogue and the action and the plot comes from my more sensitive experience as a human being, not only as a cinephile. It is as if I’m trying to build a war that grows inspiration from all the films that I’ve seen in my life, which then allows the characters to resemble me and my own personal experiences of friendship, of love, and also of my fears.

Can you tell me a little bit about your working relationship with your brother, Anthony Gonzalez [sole permanent member of electronic act M83], who’s composed the music for both of your features? I’m guessing you share similar reference points. But is it difficult to negotiate your work as collaborators and your life as brothers?

It really depends. We were under the impression that this was definitely a more difficult project, and we had a harder time finding not only the right hues and tones but especially the backbone, the core theme of the film itself. We normally send each other references and in this case the references were of course the music from porn films of the ’70s, but also from genre films. And he was the one who proposed to collaborate with [original M83 member] Nicolas Fromageau. They worked together on his first two albums, and Nicolas is a big fan of B-movies and genre films.

So they reunited to do this?

Yeah. It had been maybe 15 years since they had collaborated. The danger with this film was only creating a pastiche of all the genre films from that era, so we tried to add something more modern to it with the instrumentations. My greatest fear in this case was to have a grotesque reproduction of our own references, while my wish was to go beyond that and find a very new and original solution. The core of the process for me was to open the film with a melody sequence, to work with a concept that has gone lost recently in filmmaking—that is, music themes. This was a regular practice in the films of the ’70s and the ’80s and now we don’t seem to have those melodies anymore. By reproducing these themes, we were able to give a touch of melancholy, and to organize around different instrumentation. And so that allowed Anthony to explore uncharted musical territories, to write different music scores for these individual porn films, and for these cabaret Grand Guignol shows. That was something that at the same time scared and excited him, and it was this challenge that prompted him to make great things—great art.

Was it important for you to give this fun but somewhat dark story a happy ending? The film ends in heaven, accompanied by some rather angelic music.

I’m always quite scared of those bleak films that overwhelm the viewer. I like the noir genre but I like those to end on a sort of positive, opportunistic note, with just a beam of light to lighten up the ending. So I chose to blur the time reference in this instance. We don’t quite know where we are, what time period we’re in anymore, and we hear these notes of electronic music that is not made by my brother but by another musician, Jefre Cantu-Ledesma—very contemporary electronic music from today. That allowed him to reflect as well, on the hopes and the fantasies of today’s people, today’s youth. To me, it was all very inspiring, as I was surrounded by many different groups of people, people my age, people younger than me. I really dug the good energy from the young people—they are so much more liberated, sexually speaking. They really enhanced my freedom in a way, my freedom of creativity, my sexual freedom—it was really inspiring.

Jordan Cronk is a critic and programmer based in Los Angeles. He runs Acropolis Cinema, a screening series for experimental and undistributed films, and is co-director of the Locarno in Los Angeles film festival.