Interview: Wang Bing

Throughout his career as an independent filmmaker, Wang Bing (born in 1967) has kept returning to two main themes. On the one hand, the documentaries Tie Xi Qu: West of the Tracks (2003), Crude Oil (2008), Coal Money (2009), Man With No Name (2009), Three Sisters (2012), ‘Til Madness Do Us Part (2013) and Father and Sons (2014) are dedicated to the careful observation of common people’s everyday lives, thus bringing to the screen the few joys and many tribulations of factory workers, roughnecks, truck drivers, peasants, and mental patients in present-day China. On the other hand, filmed interview He Fengming (2007) and fiction films Brutality Factory (2007) and The Ditch (2010) constitute a historical investigation into how the Communist Party of China dealt with ideological dissent in the late 1950s, ’60s, and ’70s.

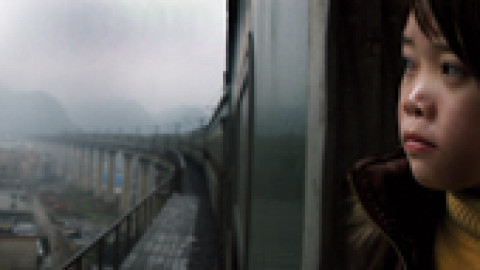

In the aftermath of Chinese New Year, Film Comment took advantage of a break in Stakhanovite director Wang Bing’s busy schedule and reached out over Skype to discuss his filmmaking practices, and especially his latest documentaries Ta’ang and Bitter Money, both of which premiered in festivals in 2016. Ta’ang follows various Myanmarese families of Ta’ang ethnicity as war forces them to leave their native villages and flee to China; Bitter Money follows young people migrating from Yunnan region to the city of Huzhou, determined to make money by working long hours in sewing workshops. Bitter Money screens on February 23 in Film Comment Selects.

Ta’ang

How are you?

I am fine, thank you. I have been so busy lately! My schedule has been very hectic for the past two years, so I am having a good rest now, recharging my batteries before starting to work again.

What’s your next move?

Traveling, shooting, editing, more traveling, more shooting, more editing.

Russian poet Vladimir Mayakovsky said it well in a 1922 manifesto: he wrote that “cinema is an athlete,” and that the man with the camera must have a lot of energy, because filmmaking is an exhausting enterprise.

Yes, filmmaking can be exhausting. Indeed, I made a rule for myself to only follow one project at a time—I cannot take more. Shooting, postproduction, festivals: the work never ends. I am willing to do anything for my movies, but unfortunately I am not much of an “athlete.” Do you remember that scene from my film ‘Til Madness Do Us Part, in which a young patient of the mental hospital starts running down the corridor and the cameraman runs after him? Well, that patient was really nervous and could never sleep, so he used to take a lot of exercise to wear himself down. I shot ‘Til Madness Do Us Part with two cameras—one operated by me and one operated by another cameraman. We tried a fixed-camera setup for the running scene, but I felt that the fixed camera couldn’t quite create a connection between the audience and the inner world of this person. I felt that only by running with him we could express his anxiety and restlessness. So I told the other cameraman, who is younger and more energetic than me, to run after the patient… [Laughter]

Given the reliance on money investments in production and profit-making through distribution, cinema is not only an athletic feat, but also a business. Do you see yourself as an entrepreneur?

In my view, the film industry is very simple: there are commercial movies and there are personal movies, both based on material foundations. Commercial movies are the driving economic force of the film industry. They require a lot of money to be made and involve a lot of people. Consequently, commercial movies need to follow certain rules other than the director’s will. However, in the film industry there is also a space for individualism, that is to say the possibility for making personal movies like the ones I make. These personal movies require less investment and involve less people than commercial ones. I am not saying that one type of movies is better than the other. I am saying that every movie has its value, regardless of the budget.

Over the course of the past 17 years, I have found my place in the film industry. I want to make personal movies, so I work with low budgets. I think that if I make a “big investment” movie, I will have less freedom: I will be tied down by the money and by other conditions. For example, if I made a commercial movie I would have to work with a huge crew, and I don’t think that I am prepared for that. I would probably end up spending too much time managing the crew and not enough time on the shooting itself. Digital technology provides a good platform for a person to make his own movie with a minimal crew, and that suits me fine. It is the way I want to work. I totally accept and embrace my status. I don’t feel it is “poor filmmaking,” in spite of the low budget. I think personal movies deserve their place into the film industry beside the commercial ones.

Your friend and colleague Lav Diaz has described at length how he managed to find some freedom within the limits of low-budget, digital filmmaking. How free do you feel as a filmmaker?

There is no absolute freedom for any filmmaker. There will always be limitations on various levels, according to the particular conditions a director works in: “less money” causes the “less freedom” of “less money,” and “more money” causes the “less freedom” of “more money.” For certain filmmakers, having little money means having little freedom, for other filmmakers—like myself—having little money means having more freedom, because the low budget makes things simpler and more straightforward. So I would say that a director has first of all to find the suitable conditions to create, to do what he wants to do. A good director always manages to work around—and sometimes break through—these limitations, and achieve his aims.

You mentioned Lav Diaz. Lav set most of his movies in the ancient forests of the Philippines. His characters live there—his stories take place there. The forest is a natural setting: it is beautiful in itself as a scenery, it is beautifully photographed by Lav, and it also costs very little money to shoot there. So by deciding to shoot in the forest, Lav has found a way to solve narrative, aesthetics, and budget problems, all in one. He made a great use of the means at his disposal—that’s what a good director does, in my view. And that’s what I am trying to do as well.

Most of my movies are documentaries. I like documentaries because they allow me to get into contact with the real life of the people. Also, the documentary form is the most viable way for me to make movies in China. By following people’s everyday life, I don’t have to look for actors and direct them, I don’t have to ask a lot of people to work together for me, and I don’t have to ask permission to anybody. The ways in which the Chinese film industry limits filmmakers become invalid for me, if I shoot inexpensive movies about the real life of the people with a small crew. That’s why I keep on making documentaries: I like genuine stories, and I like to feel free.

Ta’ang

Could we talk a bit about your cinema from the production side, focusing on your latest two documentaries Ta’ang and Bitter Money? It would be interesting to hear about the practicalities of your work. How much money did you need for Ta’ang and Bitter Money?

For Ta’ang I needed a few thousand Euros to start shooting, because the movie is set in a faraway region, at the Southern border of China. The cost of the movie is basically the cost of the journey, plus some extra expenses during the shooting, which lasted about one month in total. Bitter Money cost much more than Ta’ang, mainly because the shooting went on for more than two years, between Yunnan province and the city of Huzhou. As for my crew, it is very light. The maximum number is six or seven people, but this almost never happens. It is normally three of us, and sometimes it is only me. That’s all my budget allows. [Laughter]

What is your equipment?

For Ta’ang and Bitter Money I used a very small photo camera [a digital camera that primarily takes photos] that has the video recording option. The brand is Sony, the models are Alpha7s and Alpha7s II. I like them because they have a 35mm full-frame sensor. For these models, I have found matching Leica and Zeiss photographic lenses that allow for autofocus. Autofocus is essential for me, because my crew is so small and the conditions in which I work so ever-changing and unpredictable that I need the machine to take care of the focus by itself. Basically, I chose a small photo camera—the one that granted more flexibility during the shooting and that was easier to control. On it, I mounted very good photographic lenses whose production, unfortunately, ceased some time ago. I think the lenses I currently use are from the late 1970s or early ’80s. They are almost 40 years old. I was lucky to find someone selling them for a very very cheap price, as if they were rubbish to get rid of. I spent infinitely less than buying new ones, and they are better than today’s movie lenses, in my opinion.

If I had to give an advice to young people who want to make low-budget, personal films, I would say first of all make sure you pick the right equipment. New equipment is expensive and not necessarily better than older technology. Don’t dismiss something just because it is from another decade. If possible, familiarize yourself with the various options, and spend time at the “flea market” to find good equipment at low cost. Actually, I am very happy and proud of the equipment choices I made for Ta’ang. I think that the people that you see in Ta’ang are very beautiful. If instead of the old photographic lenses I had used the new movie lenses, which I consider very roughly made, I couldn’t have achieved such beautiful images of such beautiful people. This is only an example, taken from my personal experience. The point is that a filmmaker has to find smart ways to break through the limitations of the budget and get the right tools to do what he wants to do. This is the first step, I would say.

Once I have the right equipment, I can focus on the relationship with the people to be filmed, on understanding of the value of their existence, on the close observation of their everyday life. Documentary for me is not that you just go to some place and film anything you see. The shooting is the last part of the production, it comes after a lot of observation and thinking. For many years I have been working under the limitations of the budget, trying to find a way to shoot freely and control the production of the whole movie as much as possible. Starting from my very first film Tie Xi Qu: West of the Tracks, I became interested in all different aspects of movie production: the budget, the equipment, the crew, the relationship with the people to be filmed… I subsequently found my personal style struggling against limitations and working around problems.

What about postproduction? Is it more expensive than shooting?

It depends case by case. Postproduction didn’t cost much for Ta’ang because the shooting only lasted one month, due to budget restrictions and other things. We didn’t have much material to process. However, for Bitter Money I shot more than 2000 hours. The film Bitter Money is only a tiny fraction of the whole shooting, about 200 hours. A seven- or eight-month work on post-production awaits me to process the whole footage. I plan to make other movies out these 2000+ hours in the future. I want to tell other stories, go more in depth, add more information.

Bitter Money

We understand that you are a very concrete person and you don’t like theory very much, but there is another intellectual active in Soviet Russia that we would like to mention here, in relation to your filmmaking practice. It is Dziga Vertov, according to whom cinema must not strive to be Art, but it must try hard to provide information. What is your opinion about that?

Everyone has their own view about cinema, about its nature and function. Our perception of cinema depends on personal sensibility, and it varies a lot according to cultural differences. In my opinion, cinema is very different from painting and sculpture. Cinema is more like language, for me. You can use language to do all sorts of things. You can use it to write poems or you can use it to write an official document, a report. Film is just a tool, a platform that takes you wherever you want to go. There are no fixed rules or policies about what you should or should not do with cinema. So I always try to keep an open mind: for me, the film image is a recording of the reality of human existence in a given historical, socio-economic and political context, but at the same time it contains emotions, beauty, something more abstract that is perhaps Art. Why limit cinema to only one thing?

Talking about being open to all possibilities, there is this scene in Bitter Money where a young woman named Ling Ling turns to you, looks into the camera and says: “Come on, let’s go to my sister’s. Follow me!” Usually it is the director who tells people what to do, but in your film you are the one who is told what to do…

I am glad that I had this chance to interact with Ling Ling. When I first met her and got to know her, I realized that there is a big anxiety in her life: she doesn’t want to work in the sewing workshops, but sewing is the only trade she knows. As shown in the film, she also has problems with her husband. However, there are no real issues between Ling Ling and her husband, there are no major sentimental problems. It is just this anxiety that exists in the air between them and poisons their life. In general, as a director, I want to just disappear and simply record what’s happening in front of me. Yet, as I often am the cameraman as well, the interaction with the person I am filming gives me the opportunity to really get into people’s life and capture the truth of their existence. It’s rare to have chances like this, but it suddenly and unexpectedly happened with Ling Ling. I am so glad.

Are you also a character in your films? Sometimes we see your shadow on the wall or on the ground, we hear you breathing on the soundtrack…

I don’t care much about my presence within my movies. As a documentary cameraman, there will always be the chance, or risk, for my shadow to appear in the frame, because I cannot control the light. I cannot really help when this happens, so I don’t mind much. In the end, it is only natural: because of the way I work, sometimes you see me, sometimes you hear me coughing… Personally, I don’t want to be in the forefront. I am a quiet person, I don’t like to show off, both in real life and during the shooting. So I try to be as discreet a presence as possible, stay with the people quietly, and pay attention to what happens in front of me.

Ta’ang

Your film Ta’ang opens with a scene in which the war refugees’ shelter collapses. The Ta’ang people left their home in Myanmar and now their temporary house at the Chinese border falls down. It is a very concise, powerful opening for your film. How did you get into contact with these refugees in the first place?

The refugees belong to the Ta’ang ethnic group and to other ethnicities. They speak their own language, which I cannot understand. However, since they come from an area at the border between many states, they can speak different languages. The fluency depends case by case, but most people know a little bit of Chinese. So when I visited the Southern border [between China and Myanmar] for the first time, I met several Ta’ang women and their children. I immediately had the feeling that they were very pure, very simple human beings. I like this kind of people, I find them very interesting. So I decided to follow them and I started shooting. Since at the Southern border there is a war and everybody is anxious and panicked, I thought that the audience could be engaged by the quiet observation of this chaotic situation. My aim was not to make a film about the bigger picture, the armed conflict and its political causes, but to record the stories of the displaced mothers and children wandering around, lost. I thought that these stories that I found so interesting could also be attractive to audiences who have never been there, who have never experienced this kind of situation.

I shot the daily life of the Ta’ang people at the border for a short period, then I had to leave. I came back a second time because I wanted to shoot more material, but the women and children I knew were gone, the contact was lost. So I went to another place and met another group of refugees, whom I followed for another short period. As always, for Ta’ang my hope and my work was to find the feelings from the people themselves, and translate their personalities, their experience, their lives into the movie.

“We must stay together, we must not separate” is a phrase that we hear several times in Ta’ang. We noticed that the topic of broken families recurs in all your films…

Broken families are one of the many issues that people have to face over the course of their existence. In Ta’ang the cause of all troubles is war: refugees are constantly hiding, running around from one place to another. They are lost, they are scared. This precarious situation makes a person become vulnerable, anxious. In Bitter Money it is the struggle to make a living that triggers people’s anxiety: the workers have to leave their village and their families behind, move to another region, slave away in the city in order to make money. I want to observe people’s life, to access their inner world and show what worries them. Everybody lives in worry. If you don’t interact with other people, you will never understand their inner world and the issues they have to face every single day of their life. But when you do interact, as a filmmaker or as a spectator, then you are forced to face other people’s anxieties and unstable status, and your own anxieties and unstable status, too. We all try to find something of ourselves in the life of other people.

To get the money to pay for transport, food, and other basic needs, the Ta’ang refugees—both adults and children—work in sugar cane plantations in exchange for a ridiculous salary. Do they get paid less than legal workers?

They are paid less than legal workers, of course. It’s essential for the refugees to find a job in order to survive while they are so far away from home. The refugees are so desperate that they are willing to accept any job, any salary, any condition. This situation is not at all special, it is the same all over the world. Each person has his position in the economic chain. Nobody wants to be at the bottom. Each person thinks of his own benefit, taking advantage of other people. This is clearly shown in Ta’ang. However, Ta’ang also shows that when people are in trouble they stick together and help each other, no matter which ethnic group or country they are from. The kindness of humanity still shows sometimes, together with the greedy side.

Ta’ang

At some point in the middle of the movie, night falls and it seems like it’s never going to end. Watching the film, it’s unnerving, it’s exhausting, it’s scary…

One very practical reason for the long night scenes is related to some limitations we had to face during the shooting. In the daytime we didn’t have so much freedom to shoot, for a variety of disturbing reasons. So we shot a lot of material at nighttime, when the situation around us was quieter. Also, at nighttime human beings tend to show and share more of their true feelings and ideas about their status and the world they live in. At nighttime people feel free to speak their mind about a lot of things. During the daytime, on the contrary, they are busy with daily life and work, and it is really hard to get to know a person, because of this façade that we all have to maintain to go through the motions of our daily routine. Therefore, when I was editing Ta’ang, I decided to include more than 50 minutes of material from the nighttime footage, to engage audiences with the inner world of the refugees, to provide a more complete account of their life.

During this eternal night a group of women and a few men gather around the fire and start talking about their refugee life, their misery, their families broken by the war, wondering about the future. Being together and talking with each other helps them a little, gives them a chance to get things off their chest. Is your camera like a fire into the night, which people can use to gather around and discuss their problems?

I think that you are reading too much into the movie. There are no metaphors for me. Things are far simpler. The Ta’ang people come from a rural area in which it is very common to gather around the fire and talk. In their native region, nights are not so cold, the weather is a lot warmer than in Northern China. Ta’ang people’s life is very different from our city life: at night, they usually gather around the fire and talk for hours. The night scenes in my movie show this habit they have and how they cling to it. I guess it is an attempt by the refugees to live normally, as if they were in their beloved village back home.

Ta’ang takes us from Myanmar to China’s Southern region Yunnan to follow the refugees, while Bitter Money takes us from the Yunnan countryside to the city of Huzhou to follow young peasants dreaming of becoming rich quickly by working in sewing workshops. In the China of today everybody dreams of becoming rich, while originally the dream was to create a society in which everybody was equal…

Historically, Chinese society comes from feudalism. We had feudalism for thousands of years. And then, suddenly, China changed into a modern society. At the beginning it was all about ideology, Communist ideology. It is a long story. The People’s Republic of China was born as a socialist system: we had a planned economy, in which certain goods were produced in certain quantities, and wealth was subsequently distributed to the people. Under these circumstances, the Chinese market was limited. An individual’s productive behavior was limited and everybody got more or less the same amount of wealth. Accordingly, people had very limited possibilities for leaving their native place and moving elsewhere to improve their condition. In sum, individuals had a very limited control over their life.

The 1978 “open door” policy brought about the market economy and now the individual has more initiative, more freedom of movement, and the rule is that those who work more get more wealth. Of course, things are never so straightforward. The accumulation of wealth doesn’t depend only on how much you work, but also on power and class. But in general, in the market economy, normal people—the vast majority of people—can only gain wealth by the work of their hands, and the amount of wealth they can get is directly proportional to the amount of time they spend working. So in the city of Huzhou [where Bitter Money is set] as everywhere else in China, people seek to make more money working up to 13 hours per day. This is what the people who come from the bottom of society do. It is what they have to do to face the hardships of life.

Bitter Money

One of the ways to get rich quickly that is used by the workers in Bitter Money is a sort of pyramid scheme scam: workers basically trick their fellow-workers into investing in a non-existent business run by some shady company, in order to appropriate part of the investment money. It is a struggle between the poor…

In the economic chain, from the top to the bottom, everybody wants to have money in order to conquer a certain freedom from need. No matter how slim the chance of making money is, people will try everything they can to make profit and acquire a certain “freedom in life.” However, people coming from the bottom of society have very small chances, very few options. It is not easy for them to live in this world. Most of the time, in addition to working their asses off every day, they have to find other sources of income. So what can they do? We shouldn’t judge the people in Bitter Money too harshly for the pyramid scheme scam. Our life is very different from theirs. If we were in their shoes, if we had to face the hardships that they have to face, we would probably do the pyramid scheme scam as well.

Bitter Money shows us the capitalist trap at work. People accept to be exploited to get as much money as possible, but then somehow money just vanishes from their pockets, because they have to pay for the rent, the food, the drinks, the cell-phone, the gambling… The older man that we see drunk in the sewing workshop is a mirror held up to your young protagonists—his hopes ground up in this big machine of exploitation. Do you think that the young people realize this? Do you think that they learn something from him?

The young people that you see in Bitter Money will soon become like the older person. This is certain. Age aside, the life of all the workers in my film is more or less the same: they work in the factory, they eat in the factory, they sleep in the factory. They have no life in the outside world. They all work endlessly, they save every penny made from sewing clothes. The only difference is that the young people have less of a burden to cope with: they are in good health, they are still strong and energetic, they haven’t married, they have no children, their parents are still relatively young and perfectly capable of taking care of themselves. These young people don’t have too much pressure from life yet. If they had as much pressure as the older guy that you see in Bitter Money, they would start breaking in the same way. The older guy has been slaving away for such a long time and his life is still the same. His condition didn’t improve at all. Therefore, he is disappointed with himself, he becomes bitter, he gets drunk. He has a family to provide for: a wife, a child. Plus, his parents are old and ill, and they need money, too. The pressure is too much for him to handle. In comparison, young people have less pressure and, after spending for board and lodging, they have something left for themselves. So even if they all belong to the same social class, the young people think that they are better than the older guy and laugh at him. In my view, the fact that the young people laugh at their older fellow worker means that they haven’t seen life clearly. They haven’t seen their future clearly. They haven’t learned anything yet.

This is the delusion of young age, it is very common. I experienced the same delusion myself. When I was younger, I lived passionately. I was very passionate and idealistic about each and every movie I made. I still am in a way, but after almost 20 years in the film industry I finally realized that it is impossible for me to break through certain limitations, certain invisible barriers. Of course, people would think that these limitations come from the lack of money. They do, but actually it is not just about money. It is the way the whole industry works that creates limitations. The mainstream ideology of our society creates limitations. The fierce competition between people creates limitations.

I knew about these issues from the start, ever since the beginning of my career, but I didn’t care much. I thought that many issues will soon be solved somehow. I thought that I could solve all my problems simply by working hard. Unfortunately, I was wrong, and I am now facing the same challenges that I was facing when I made my first film. Nothing has changed for me, nothing has improved in all these years. It is I who have changed over time. I changed from a person who has hopes and passion about the film industry, a person believing in the creative power of imagination, to a disillusioned person who knows that the reality of the film industry will never ever change. So I have come to accept the fact that I have to live within this immutable system. Now I feel released.

At the beginning of my career, I thought that there were a lot of possibilities in filmmaking. I was naive, I was dreaming. As time went by, the possibilities vanished one by one. When you cannot achieve your dream, what can you do? You learn to live in the real world. That’s why I totally accept and embrace my status. Now I simply try to reach my dream within the concrete possibilities that I have. That’s the only thing I can do. An individual is too small and weak to change the whole society. The people in my movies and I, we are all the same in a way: we are frail, we work hard and we live day by day.

In Ta’ang people always talk about money and money is always shown. In Bitter Money people always talk about money but money is never shown.

I am not sure this fact you highlight was intentional on my part. But I would like to talk about the title “bitter money” for a minute. The title is very important and it was chosen carefully. In Huzhou “bitter money” is a slang expression that workers use to say “I am going away from home to work.” It is a very common way of saying in this city, everyone uses it. Coming from Northern China, I had never heard of this expression before, and I was curious about it. So over the course of the shooting, I understood why they call work bitter money: all these workers have migrated to Huzhou from other regions, with the hope of making money. The word “bitter” alludes to the discriminations that the individual has to face when he is away from his native place, the hardships and sadness a person has to face when he is away from home to earn money, working like hell all day, every day, with no personal life whatsoever. You can see the money or you cannot see it, but it is the “bitter” taste of money I am interested in.

Bitter Money

Bitter Money won the award for best screenplay at the Venice Film Festival, but of course you wrote no screenplay for the movie. Did you find it strange to win this prize?

What can I say? I don’t have any particular feelings about this prize. The judges decided to give me the screenplay prize. I cannot control the way judges think. I accept whatever prize festivals eventually decide to give me, and I am happy that people show interest in my work.

As all your documentaries, Ta’ang and Bitter Money have an open ending. Why do you never “close” your movies?

I understand what you are getting at, but personally I don’t want to make any metaphor out of my open endings. I want to engage the audience by showing an individual’s life, not by making metaphors. My movies can only observe a more or less short time period in a person’s life, then the shooting is over and postproduction starts. Let’s say that, since I cannot foresee the future, my films always have an open ending. [Laughter]

There is a domestic violence story in Bitter Money. What do you think of the law passed by the Chinese government in late 2015, outlawing domestic violence? Do you think it is useful?

Laws are just formal rules through which people try to deal with the issues that they have with each other. Unfortunately, issues between husband and wife cannot be solved by one single law. These issues are so complicated, human beings are so complicated.

Are Ta’ang and Bitter Money getting released in Chinese theaters?

No, they are not. All my movies have never been released in Chinese theaters.

Why?

There are pre-conditions for movies to fulfill, if they are to be released in Chinese theaters. In order to be released in China, my movies would have to pass censorship from the State Administration of Radio, Film and Television. I have never applied for this censorship exam and I never will. I think it is boring and meaningless. Ever since the beginning of my career, my one and only wish has been to be able to express whatever I want. So I will never let other people “examine” my movie. I don’t need the approval of anyone.