Interview: Todd Haynes, Ed Lachman, and Mark Friedberg

A director known for his studious craftsmanship as much as his experimental approach to mainstream storytelling, Todd Haynes is among the most exacting, technical filmmakers working in American cinema today. Always digging into the past, Haynes is geographically and culturally specific as he excavates earlier eras, which serve to comment on the now: the stringently bourgeois L.A. of the ’80s in Safe and the weather-beaten Depression-era version of that city in Mildred Pierce; the suburban New England ’50s by way of Sirk in Far from Heaven; the various strands of pop Americana, from the Dust Bowl to the Warhol Factory in I’m Not There.

Of course, the precision of these re-creations relies on a crackerjack team of like-minded artists, and Haynes has the closest thing to a troupe of regulars going. Haynes, and two of his recurring collaborators, cinematographer Ed Lachman and production designer Mark Friedberg, sat down with me to discuss their nearly miraculous work on the new film Wonderstruck. Following two deaf children—Rose (Millicent Simmonds) and Ben (Oakes Fegley)—born 50 years apart, but whose lives eventually cross paths in surprising ways, Wonderstruck, based on a young-adult novel by writer and illustrator Brian Selznick (The Invention of Hugo Cabret), mostly jumps between ’20s and ’70s New York, each story line requiring its own visual approach and identity, while at the same time needing to speak to one another across time and space.

Read my full review of Wonderstruck here.

Where are you jet-lagged from?

Todd Haynes: I got back from Portland, and I was also in Europe. We showed Wonderstruck in Locarno, and they did a sort of lifetime achievement award for me, something very sweet, hopefully very precocious.

How does getting that lifetime achievement award make you feel?

TH: Old!

Mark Friedberg: So you got the lifetime achievement award, what’s next?

TH: The After-Life Achievement Award. All of my after-life films. Me and Shirley MacLaine. But you know, the last time I was in Locarno was 1991 with my first feature film, Poison. It does feel like a lifetime ago. So many people have passed away. The last thing I did there was an intro for Poison, and I started to break down. I just lost it when I was talking about all the people who’ve died. And this is well beyond HIV—just a strange number of deaths related to that film, very sadly.

Actually I was thinking about Poison when I watched Wonderstruck. Not just because of the different formats.

TH: We’re going to double-bill them, I think. It’s perfect for the whole family. My first kids’ film and my latest kids’ film. [laughter all around]

That does branch off to a good question. I know Wonderstruck is a different film for you. But at the same time it’s not. And I’m interested in the ways it isn’t. And I was thinking a lot about Poison and even I’m Not There. It seems that a lot of what you do in your career is about historical curation in a sense, so I’m wondering, at the outset is that what first attracted you to the material?

TH: Absolutely. In this sense it’s literalized in the narrative itself and the agendas of the two kids, particularly Ben, and then institutionalized in the form of these living relics that curate history and preserve and maintain the past. But then I think what’s beautiful about the structure of Wonderstruck, which is of course from Brian’s book, and was already very cinematically activated in his first script adaptation, is that the very question, the mystery at the core of the story, is played out by the structure itself. So the form really is completely fundamental to the themes and narrative.

MF [to Haynes]: If it didn’t have two periods you’d find another period to look through to see this period. So this gave you something that’s kind of natural to you as a way of thinking about time, to compare it to time or place. That’s probably a reason why it made sense to you right off the bat. You didn’t have to go look for a structure, a Todd structure, because there was one there.

TH: Whenever you do a period, you’re always, hopefully, thinking about the period you’re in. And that’s why you choose the period you’re selecting. Fassbinder had taken the Sirkian melodrama and applied it brilliantly, cogently to contemporary German life and adapted All That Heaven Allows to Ali: Fear Eats the Soul, set in his contemporary time, and I far less imaginatively just took it back to the ’50s [in Far from Heaven], but we were just embarking on the Bush era, and it felt like a relevant era to be taking about our present moment in, through the guise of that particular genre. But yeah, here we have the two frames speaking to each other.

It almost feels like there are three to me, since you also have the silent movie within the 1927 passage, and the silent movie has its own vernacular. So I’m wondering how you envisioned the 1927 section of the film and then the film within the film. They have their own visual languages. The way Julianne Moore, as a silent film actress, is using her face and body is very evocative of Lillian Gish.

MF: We looked at The Wind. That was our inspiration.

Ed Lachman: We looked at The Last Laugh from 1924, and the height of the black-and-white era was 1927 and 1928, when The Wind was made, and King Vidor’s The Crowd.

There’s a great, direct visual reference to The Crowd in the climactic sequence.

EL: Todd’s idea was to connect the two time periods and stories in a 2.40:1 format. To be true to the ’20s black-and-white silent period, your frame would have been 1.33:1. But he wanted to connect Rose’s story in the silent period in the ’20s with Ben’s story in the ’70s, so he made the choice to give fluidity to the story in one format.

TH: 1.33:1 would be traditional for a silent film, and we do preserve that in the film within the film, Daughter of the Storm. But not in the whole black-and-white section. And there have been some critics who have been like, “Well! If he had really done a real silent film it would have had a 1.33 aspect ratio!” It’s like, no, we were making one movie, and it’s very important to have a fluidity and a conversant freedom formally, stylistically, between the two. And it was never meant to be a rigidly academic simulation of a silent film and its vernacular. At the end of the 1920s before sound came in, silent cinema had basically established any and every form of filmmaking that you can imagine today; it was already there.

MF: Well, as Todd was saying, the reason Brian chose these eras is not arbitrary; it’s the narrative. So that Rose can experience this film like everyone else and that not being able to hear it doesn’t diminish her experience, and that also in a way this is how she connects to her mother, is imperative. And that’s the year she can see that this might be taken away from her. She walks out of the theater and the sound equipment arrives—that’s what 1927 was on the one hand. On the other hand, adding sound almost unmodernized what was going on. The silent stuff was looking for other language; it was some of the most modern filmmaking we looked at. That was the most surprising part of it, looking back and seeing forward.

As far as dealing with the periods, the other built-in phenomena of these two periods is that one is of ascension and exuberance and growth, and one is about destitution and nihilism and aftermath. And that’s the ’70s and the ’20s. New York is probably more on the exuberant side right now, ironically. In a weird way it was harder to find the ’70s than the ’20s, because the ’70s have been scrubbed. Right now you can’t find anything as bad as what good neighborhoods looked like in the ’70s. I grew up on the Upper West Side at that time, and when I looked back at the pictures, I was amazed; it was like tumbleweeds of garbage blowing across your knees. The lots were vacant. It was rubble. So the despair was not just emotional, it was palpable, it was there.

Did you feel like you were also making a film about New York today? I watched it with some people born and raised in New York, and they were very moved by it.

TH: I think you’re feeling now a loss of a lot of the historic, marquee parts of New York’s history. It’s a city that, as all cities do, will continually be reinventing itself, demolishing the past and reasserting the future. That’s more true for the ’20s in this film than the ’70s, as Mark was saying, it’s really a place that might lend more to a sense of robust economic optimism and potential. This is also right before the crash, so there’s a kind of euphoric delirium of potential ingrowth. And that’s really what we wanted Rose to walk into. The rhythms of the city and the modernity of the city to be something you feel in her steps and in what she sees, and in the upward thrust of the architecture.

MF: And she’s connected to the architecture. It’s been a part of her life and she’s been staring at it all her life. It is of her, and it’s what she becomes. She becomes the person who makes the city, who makes the model [the diorama of New York].

TH: For a deaf person, the 1920s was a very difficult time to be on your own. We were still in a dark era on how to educate deaf people. And ironically all the answers Rose ultimately finds, all the answers all the characters ultimately find, are found in the ’70s, a much more economically distressed, challenged time. But also a time with a lot more progressive legislation and opportunity for deaf people. In a weird way, that’s where this hybrid family comes together at the end of the story, in this sort of tattered debris of the ’70s. In the ’20s she’s locked up and she comes to the city with all kinds of aspirations and finds that her mother can’t fit her into her life either. So there are contradictions on both sides of what you see in the depiction of the city. But we also were paying homage to two remarkable institutions that have specific relevance to these eras—the Natural History Museum, which spanned both decades of course, and the Queens Museum and the Panorama, which was not that old in ’77, it had just been built in 1964—as testaments to a kind of city that endures.

EL: Also, we thought the language of cinema in that time period was emblematic of the time in the ’70s. We looked toward The French Connection. Owen Roizman was at the height of his career, he did The Taking of Pelham One Two Three and Three Days of the Condor. He was capturing the city in a cinematic language that was new for Hollywood—shooting in the streets, shooting with available light, pushing film stocks, with the zoom. He even complained to me when I called him up to talk, because Todd also wanted to use the tools that they used in the ’70s and not try to re-create it with a dolly track the way they would in the streets today. So we found they were using Western Dollies in the streets on oversized pneumatic tires, so we used the same tools to do those shots. And we implemented handheld to create a visual language on various suspension devices to create the ’70s feeling of movement in how they created their shots.

Owen Roizman was still complaining 50 years later that William Friedkin was making him use the zoom lens, because cameramen always want to hide what they’re doing; they don’t want to be so overt. But Todd wanted to reference that, too. So I think all those things add to the feeling of the subjectivity of the camera.

It’s an amazing experience watching a movie in the ’70s style but from the point of view of a child. I feel like I hadn’t really seen that before, like melding two different styles.

MF: I was thinking a lot about it because I was a child in that time in this place, so for me it was a very nostalgic experience to make these worlds, literally remaking stores where my parents took me to shop and buy my shoes. Now we’re living in a time where they’re turning the sky of New York into glass, you can’t find a vacant lot, nobody can really be here unless they don’t belong here, or they have the means to sort of live on top of society.

TH: I was compelled to look back at films that affected me a great deal when I was younger. They weren’t necessarily films set in the city, they were films that just underscored and ignited the point of view of young people in unique ways, like Walkabout. Or Sounder was a film that I loved, the Martin Ritt movie from 1972. And I thought, oh, that moved me so much as a child, I’m going to go back and it’s going to be a very sentimental, manipulative movie about a dog and a sharecropping family in the ’30s. But it is so restrained, it is so elegant, it is so sophisticated. It is told from the point of view of the son, who has to go on a sort of journey to find his father, who’s been imprisoned just for stealing some food to make ends meet in their poverty. And, again, I think I felt that what Brian’s concept offered me was a chance to do something extraordinarily artful, sophisticated, nuanced, mature—for kids.

EL: Also, you know it’s all shot on film, even the black and white. We didn’t shoot color film and then make it monochromatic digitally. It was shot on black and white, the color is color; we pushed a stop to give it grain. I tried to reference this, I realized I was in my mid-twenties in the ’70s and I had worked with Sven Nykvist, Robby Müller, and Vittorio Storaro in New York.

TH: You’re such a show-off. Such a name-dropper, dude. [laughs]

EL: I’m just trying to remember that the colors have like a magenta, yellow look to it, because film back then didn’t have the color range that it does now. So when you underexposed the film you got a magenta green feeling, and that’s what we tried to enhance.

[To Haynes] I think there’s a certain amount of playing with genre that you’ve always done, and in this case it seems like you’re playing with the form of a children’s film. That’s how I took it.

EL: Plus, Todd tested it with children.

MF: They had better insights.

TH: I think what we’re learning is what I learned when I started. I had more experimental ambitions as a filmmaker even before I made my first feature film. At this historical moment, you sort of saw an infusion of experimental into narrative traditions—you could see that happening in Sally Potter’s Thriller, a short film she had made before she started making features, and even in David Lynch’s Blue Velvet. I felt that Superstar and later Poison showed me that audiences I might have considered outside the experimental audience were extremely fluent in narrative language, and could shift from one style to another with great dexterity. And I think I learned that kids actually can in some ways deviate from narrative form and convention more freely and with less fear than their parents. I usually bring people in for friends and family screenings while I’m cutting, to learn how cuts are working and taking form. In this case we brought in kids from the very beginning. And the kids, who were given little things to write after the screenings, would offer myself and Affonso [Gonçalves] the editor the most specific, most clear-sighted guidance and signposts along the process, exactly what we needed to hear. They were incredibly astute and patient during longer cuts of the movie, they could handle the lack of dialogue.

Were there specific things the kids said that made you change course on certain things?

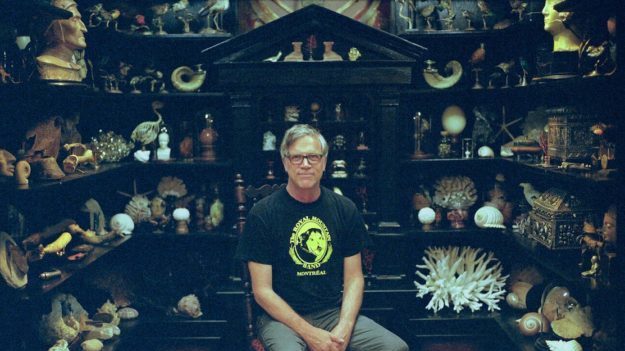

TH: Yeah. One of Mark’s most extraordinary sets in the film, and this is saying a lot, is the Cabinet of Wonders, one of the most exquisite creations by him and his amazing team. So we had a cut of the film that really allowed Rose to explore the Cabinet. And at one point in the story, as we were trying to find places to shorten the film—was it playing too long, are we milking it, are we falling in love with it too much?—kids wrote, “Why does the Cabinet of Wonders mean so much to Rose?” Two kids out of 12. And all of a sudden, I was like “Holy shit, they’re right.” It means everything to Ben.

MF: And to us.

TH: And to us! And maybe that was getting in the way. But she just happens into it. It’s a place to hide, it’s accidental, it’s circumstantial to her. It’s a piece of evidence that she collects from her past, but it’s not the thing that she makes at home furtively in her bedroom. It’s not the thing she went in search for. And I said this to Brian Selznick, and he’s like, “God, I never thought of that before.” And we didn’t ask them the question. They completely offered it.

Can we talk more about the Museum itself? It’s a rich, fanciful, but very real place. So how did you take what’s there and heighten it? What was the idea of the museum itself?

EL: Well, we had a real problem. We would only be allowed to shoot there at night after-hours.

TH: We had to load in and out every time, we couldn’t leave equipment there overnight if we set up lights.

EL: So I did a number of tests because we were shooting film, and I could have shot film, but we finally made a decision to shoot that digitally.

MF: But that was also because they wouldn’t let you light the exhibits.

EL: Right, those dioramas. It took three months to negotiate for Kino Flo fluorescent lights in the wolf diorama.

TH: Each diorama is controlled by a different committee of donors… it’s an entire bureaucracy.

EL: And the dioramas have to be the brightest thing in the scene because that’s what it would be to the eye. The focal point is those dioramas, so I had to balance whatever we did off of the dioramas so what we do isn’t brighter.

MF: The good thing about the museum is that it’s a place to get lost in and fantasize, but the movie’s about curation; it’s about the emotional power of tactile things. Some of the museum we actually had to remake. The meteorite, we literally rebuilt that. And we had to pretend that the Cabinet of Wonders was in the museum, so we had to rebuild sections of the museum to make it seem like you’re coming around a corner of the Museum of Natural History in all of its bigness and glory and then into our hall that matched a real hall there.

I like what you were saying earlier about the “emotional power of tactile things.” I felt the same way when I saw Jarmusch’s Paterson—a film you worked on as well. There is something general going on in the culture with a move back to artisanal, analog things, but I also see it in a spate of films recently. I felt it also in Jarmusch’s previous film Only Lovers Left Alive. These are movies about the pleasure of tactility, the loss of things, of objects.

MF: Objects can be repositories of something, or reflections of something. I mean, it’s a rock, it has its own inherent meanings, but it’s whatever I bring to it, the experience I had the day when I found it. I mean, my house is covered in rocks, and each of them is about a time I experienced, or a place or something. They’re little poems in a lot of ways. Things to infuse with our selves. And then they can hold those infusions for us as individuals.

TH: They’re also ways that we manage death and materiality. We’d love to believe we live in a digital world, and plenty of movies fantasize about overcoming death and mortality. Hasn’t happened yet, in my experience. And that’s what natural history museums do, they’re little ways of managing death. These are the spoils of our hunting and our exploration as a species, which we put into settings of their habitats and re-create a sense of life, but it’s really about studying them as living emblems of our victory over them. And in many ways that’s what Wonderstruck is about, it’s about Ben coming to terms with death: a death that he knows happened, his mother’s, and another death he doesn’t yet know has happened, his father’s. And that’s what so coherent about all the themes and ideas in Brian’s story, they all line up: the diorama that’s a little cabinet of death that his father made is also the last memory linking him to his father that he doesn’t even know he has.

MF: Or as adults when we look at a diorama we might be thinking about demographics or politics, but as a kid you look at these frozen moments as eternities. It became very much a part of our language, not just Ben’s language but our language of telling the story. When Ben is trying to understand the story that Rose has laid out for him about his prehistory and early history, we use the language of dioramas as a way of animating, as it were, those individual moments. It’s the part of the movie I can’t watch without crying. Somehow, shooting little paper dolls that don’t move became one of the most emotional parts of the story.

I was thinking that device was an ingenious solution to a narrative problem: how do you get all this exposition in there? Because in the book, it’s page after page of text. It made me think of Cambodian filmmaker Rithy Panh’s The Missing Picture, made a couple years ago, where he used little figures to chart personal tragic history.

TH: That’s an overwhelming film. Also, what the Natural History Museum is about, and what draws Ben to it, is that it really evokes what a production designer does in movies. They’re like two-dimensional tricks of three-dimensionality—that’s what cinema does. And they’re re-creations of time and place. I feel like what was so cool about the script that I got was that it asked every aspect of my creative team to take a lead role. The music is intensely important, and it steps up to the plate in this film. As does the editing, as does the production design, as does the cinematography and costumes. But none of it is imposed, none of it is extraneous to what the story is about and how it needs to work on you as a viewer. So it calls on the purely cinematic components of our medium in every conceivable way, the plastic and the theatrical.

And beautiful sound design, too. There were so many great sound bridges and shock cuts.

TH: With this movie, you can imagine, you couldn’t even put two shots together without having a temp music track. Because there was no way of judging how the silent film was going to work without music underneath it. So music had to be curated before we had a composer writing a score. Carter [Burwell] and I were talking about the music well before we started shooting the movie, but we didn’t have it yet. So we had to find music and sound as stand-ins for what the final track was going to be and how the film was going to function as a whole. Because it’s a movie about a loss of hearing, but it is largely made by hearing people, largely for hearing people, though we had an extraordinary non-hearing person at the center of the entire experience. It’s impossible to think of this movie without her there.

That’s Millicent Simmonds?

TH: That’s Millie. But it’s really a way of asking hearing people to think about what it means to not hear, and how we use our sound design and our music as indicators of what could be an absence.

MF: I kind of felt like Carter’s silent score was dialogue in a way. As opposed to being the thing that helps you know what to feel, it’s actually the thing that tells you what’s happening, or rather how they communicate, through this music.

TH: One of our soloists in the score is Dame Evelyn Glennie, who is a deaf percussionist. World-renowned. And she plays pitch percussion, not just rhythmic percussion. She’s amazing. She looks like a little grown-up Rose. She’s got long, long, long gray hair and has this wide stance and she holds three mallets in each hand, and she’s phenomenal. She feels it in her body, she has a trace of audibility that she uses in the headphones turned way up, and she also plays off the other percussionists.

You’ve all collaborated many times together now. Can you talk a little about your working relationship? How does it start? How does it proceed? Just getting the visual idea of the film…

EL: Nobody does more visual research than Todd.

TH: Except Mark. And Ed! I mean, we’re all three art nerds. We share that at our core. Mark and I actually went to the same college at the same time, and we even took art classes together—a long time ago, we will not say how long. But I share that with them. Because they’re both so intrinsically inspired by not just film but visual art, photography, theater, sculpture. I begin with an image book that pulls together references from films and photography and history, and you know, the relative elements to the film. There’s The Night of the Hunter, there’s Sounder, there’s Midnight Cowboy. If you think that’s ornate and detailed, then Mark takes it to a whole other level, incorporating schemas based on locations we’re starting to put together. The amazing thing about Mark, because he knows New York City so well, is that we really begin in a car, exploring the city.

MF: It’s my best design tool, my car. The thing that we do well is that we use both of our lobes. On the one hand we’re studious and studied, and know that facts and demographics and history and politics and art of that time. On the other hand, we’re all kind of wild artists who want to find new ways to take all that information and see if we can’t get it to an emotional structure.

EL: I know I’m on the right set when I’m finding things that I think I discovered but Mark put them there for me to discover. And for Todd, he has a shot list that’s very specific, but when he’s on set he improvises, knowing what that shot list is, to discover what that shot is, and that gives the image a life. And that’s rare. Because a lot of times, people either go unprepared to try to find it, or they go with a plan and they’re so stringent to that plan that they miss what’s in front of them. And Todd has the ability to do both, to go in with a plan but then improvise what’s there in front of them. So for me as a cinematographer that’s the best of both worlds that I can work with. The sense of discovering something that I found but he put there for me, and Todd discovering it through the camera.

That’s a perfect metaphor for this particular story, too—discovering something that was put there for you 50 years ago.

MF: Change the poster, that’s good!