Interview: Robert Richardson

Robert Richardson on the set of Hugo (Martin Scorsese, 2011)

When talking about the people who make movies, we often reserve the term “experimental” for directors. You hear plenty about the “experimental filmmaker,” but rarely see that adjective applied to other parts of the filmmaking craft. What about experimental actors, say, or experimental editor—artists who push the boundaries of their respective forms even while serving the vision of others. If we’re to think about what might constitute an experimental cinematographer in today’s Hollywood, no one fits the description better than Robert Richardson.

Richardson’s career is defined by his long-standing collaborations with some of contemporary cinema’s biggest and brashest talents: 11 films with Oliver Stone, seven with Martin Scorsese, six with Quentin Tarantino. Beginning with JFK, Richardson and Stone created a new kind of visual language for mainstream studio filmmaking, jumping freely between film stocks and shutter speeds, moving abruptly from color to black-and-white and back again. This kaleidoscopic aesthetic—oft-intimated and rarely duplicated throughout the 1990s—re-emerged in future Stone collaborations (Natural Born Killers, U Turn) and work for others (Bringing Out the Dead, Kill Bill), and established the Richardson Look: frenetically mixing stylistic modes within the framework of a single narrative movie. His most recent work—Once Upon A Time… In Hollywood—is just the latest example of that ability to juggle multiple styles, with its pitch-perfect recreations of poliziotteschi and TV Westerns alongside its evocation of sunbaked 1969 Los Angeles.

Across four decades, Richardson’s lensing has always exhibited a sense of play and willingness to try out new techniques, new equipment, new ways forward. Like many of his close collaborators, he’s a voracious cinephile, but Richardson’s camera style isn’t merely referential: past, present, and future collide in his work to create something wholly new. He’s an intuitive artist, and one can’t help but find a kinship with Richard Boyle—the go-for-broke war photographer played by James Woods in Richardson’s first narrative film Salvador—another cameraman committed to finding poetry in the middle of a combat zone.

Robert Richardson: I’m going to let you know right off the bat: I’m not technical.

It’s interesting to hear you describe yourself that way. Something I most associate you with is a mastery of cameras, lenses, stocks…

That’s extremely odd you say that—a mastery. I’m not a master in terms of the technical [aspects of photography]. I have worked with multiple formats: in terms of film and digital, in terms of lenses. And this also alludes to lighting, whether you’re dealing with Maxis, or LEDs, or whatever—I don’t see these things. I don’t have the capability; I’m not that type of cinematographer. The thing I know is: if I work with a camera, or a film stock, digital or film, I know what the camera’s capable of because I’ve worked with it. And lenses I know plus or minus, but there are people well better-suited to a T vs a C vs an E—all I know is what I like when I see it, but I can call up a C because it has closer focus, or a T because it’s sharper, or whatever it might be. There are only two film stocks really available at this point. I know what an Alexa 65 is, I know what a Red is, etc etc. I’m just not that person.

I can sense you’re discovering or rediscovering things each time you shoot a new film. A lot of filmmakers are resting on their laurels after several decades, but there’s a restlessness to your work, like you’re still finding what excites you.

Are you writing my biography?

(laughs) I’m not! Not yet, anyway.

That’s exactly how I feel, exactly what you said. I don’t know what my laurels are. What I do know is: every time I start a film, I have to start all over. And it doesn’t matter what I’m shooting, in whatever medium, I have to learn it all over again. And I’m always frightened about how to expose. I carry meters all the time. I’m looking back, especially with film. I’m more frightened with film. With digital you have a monitor which is telling you: this is your exposure. I still take meter readings because I don’t believe the monitor. I don’t rely upon anybody telling me, “you’re underexposed, or your an F-stop over.” I don’t look at that.

I love making film. Film being movies, not the method in which it’s captured, and I just try to tell the narrative. That’s all I care about: narrative.

People understandably pay a lot of attention to the Stone and Scorsese and Tarantino collaborations, but you’ve worked with a number of directors multiple times: Errol Morris, John Sayles…

I love Errol. No one’s ever mentioned Errol Morris or John Sayles in an interview before.

I can’t believe that. Some of your most accomplished work has been for those filmmakers.

Errol’s a genius. A fucking genius.

Fast, Cheap, & Out of Control (Errol Morris, 1997)

Fast, Cheap, & Out Of Control really pushes that multidirectional style.

That stems directly out of JFK. The original editor was Hank Corwin and if you look at that with JFK, Hank Corwin’s isn’t listed as a primary editor, but he is so fucking present. He had a company called Lost Planet, and his work is amazing. You’ll see this immense, immense tidal wave of creativity. He did National Born Killers with Oliver.

JFK moved us towards Errol, and Errol was able, I think, for the first time, to take all of those mediums — 8, 16, 35, etc — and tailor them in a way that made a gorgeous symphony. For example, the mole rats. I said, “Errol, I can’t get a camera in there. How am I going to do this?” And we brought in Roto Rooter. We stuck the Roto Rooter camera down the tunnel to shoot the mole rats. Roto Rooter goes down toilets to find out where the roots are. It seemed like such a brilliant concept. Experimental, definitely. Like, Brakhage: hello! We’re going back to your roots and flying with you.

Also JFK represents an immense movement in a symphony of—I used the word symphony twice in the last minute, which I don’t ordinarily do—a remarkable cohesion of 8, Super 8, 16, 35. Remarkable. And also changing the scale and size of a frame, whether it’s 2.40 or anamorphic, whether it 1.85 or 1.33. That movement was extraordinarily special for me, and Oliver willing to allow it in NBK where it was: let’s sleep with Jackson Pollock.

How do you go about making those specific choices then? And how do you guarantee that cohesion?

With JFK, everything had a specific era: it went to this, it went to that. The assassination: 8mm. In JFK, it was all pointed, why we chose the medium we did whether it was video for Jack Ruby, etc. After that, when we got to NBK it was more about textures. It was not as if something told us what to do, it was more about, “oh, this is what we’ll utilize.” With Errol, it was the same thing. Nothing told us what to do.

For example, I would shoot work, then take the dailies home, and rephotograph them off the television set in my hotel. And I think that aspect—not directing yourself to something or understanding completely what you’re doing—providing a director to a texture who’s willing to accept that. Some films cannot move that direction, obviously—it’d be too complicated. That requires knowing, “I’m gonna play.”

Gary Oldman in JFK (Oliver Stone, 1991)

That certainly demands a lot of trust from your directors.

I think that’s true. With Quentin, which is my longest collaboration of late, in my career, I don’t think it’s about formats. He’s very specific about what he wants. I think it’s about trust in making something that is lit, has the quality of the image that he sees in his mind. Or better than he sees in his mind. That’s what beautiful about my relationship with Quentin: to achieve something he has seen for four or five years and then on the screen it becomes something more than he had hoped for.

A majority of the films you’ve shot have been set in the past, but they don’t feel like what I think of as “wax museum movies.” They’re very fresh and immediate.

If I fail in that aspect, I’m not allowing a film to feel like it’s alive now. And it should be alive tomorrow, and it should be alive forever. I don’t believe I make any films that will be dated. They’re not going to fall apart. The directors I’m working with are mostly directors and writers, and that’s a huge difference for me. I try to create something that’s timeless as much as possible.

Let’s go back to Platoon. Salvador. First two films I made, more or less. They live. Wall Street feels a little bit more dated but yet somehow it still resonates today. I think that if we look at the majority of the work I have shot, especially when I found a level of confidence, and was able to aid a director in a way I certainly was not capable when I started. We’re creating films that as much as possible will be remembered forever. I think Once Upon A Time… In Hollywood is a timeless film, without question. It will exist. You will watch it in ten years. Certain films I watch now and go, “I’m not going to see that again. I saw it, I don’t want to see it again.” [laughs]

Other films I see and go, “oh!” For example, there’s a Russian film—have you seen the Russian film that was put into the nomination?

Beanpole? Full disclosure: I actually work for the company that’s releasing Beanpole—I know it well.

I love Beanpole! I thought it was the best foreign film entry. The most amazing film is a 27, 28-year-old director who created the most, for me, substantial film. The two female lead characters. It was simply brilliant. I like Corpus Christi. I love Parasite. But [with Beanpole] I thought, an amazing film. I fell in love. I suddenly saw Russian cinema in a way I’ve never seen before. Now of course I’ve seen Tarkovsky, etc., etc., all the way through. I’m suddenly looking at Beanpole and I’m thinking: he’s moved it into another generation.

And Corpus Christi as well. I never saw what was coming in that film. Which is why I love a foreign film, they don’t live by the financial whims we live, which are much more predictable and more commercial overall. I’m not saying that’s bad, I think that’s good, because we need a commercial world. We need to make money on films, otherwise there’d be no industry in Hollywood.

Are you regularly watching a lot of new releases?

I watch any film that’ll come my way. Any film. I live on film. I don’t have a relationship. I come home—now I’m shooting, I come home and go to bed. When I’m not, when I have a day off like this, I can watch five films in a row.

I want to state the fact: I rent my movies. I do not download something for free. So if it’s on Apple I pay for it. I do not like the concept of streaming for free. I think the artists need to be paid. Same thing with music. I do not take free music, I pay for it.

Brad Pitt in Once Upon A Time… in Hollywood (Quentin Tarantino, 2019)

Within your longstanding director collaborations are regular collaborations with actors: Leonardo DiCaprio, Brad Pitt…

I’ve done four for Leo, three for Brad.

How does that relationship change over time? I’m thinking about how you frame and light them as they age in front of you.

It doesn’t change. I shoot them according to the scene. It could be Aviator, it could be Inglourious, it could be Django, etc., etc.—I’m shooting a sequence and it’s in the middle of a film. Or it’s amidst a film, and we’re working toward an artistic line, a creative line. I work with the actors the same way. I’m not, “Oh, Leo’s here—I’m going to light him differently than anyone else in the scene.” No. I light everyone as they should be for a sequence. That’s it. That’s the success or the failure of my work.

But there is something different that happens. When you’re with someone for that many years, there’s a trust that assembles, that builds between two humans. It starts in the very early days and at that time it’s respect or whatever. But it alters and snowballs. That creative snowball becomes: I trust, and I look, and I do, and I want, and it goes. In that manner. Brad trusts me to shoot him as best I can whatever the circumstance might be. As well as Leo trusts me. It’s not a failure of communication — it’s very similar to working with my crew. With any friend, it’s a capability of seeing and looking without talking. And then I capture that process as best I can.

It must change emotionally for you, though.

Okay. That’s a complicated question, but no: there’s never a question mark. I love Leo and I love Brad and I’ve worked with them a lot, and if you can consider an actor is a friend in your life, they’re both friends. And they’re friends in a way that only a cinematographer and actor can have, because you have to believe in each other. They have to believe you are going to capture them as best as possible. In the best manner possible.

It’s unwritten, but it’s also the same way you work with your lover. How do you work with your lover, your wife, your partner? You don’t have to talk. You can look, and both of you know the weight of a collaboration that is taking place. If there’s a problem, each one of you can signal without actually having to signal. Just a look of the eyes and it changes. I can touch the stomach of a woman and know that it’s moving. I can delve lower, I can touch legs, I can touch heart, and I can feel it. That element is not necessarily representative of anatomy as much as it is how we choose the language in which we can sell our art.

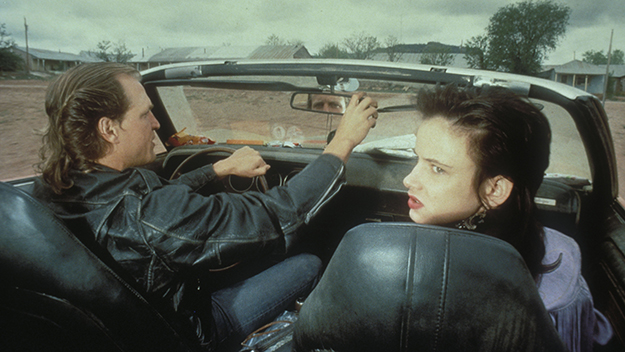

Woody Harrelson and Juliette Lewis in Natural Born Killers (Oliver Stone, 1994)

Are there ever advance discussions with the editors, the people most responsible for shaping your images?

I have no conversations with editors at all. Other than Hank Corwin, and that was on Natural Born Killers. But rarely. It’s a director’s medium. I do not talk to an editor.

What form did those conversations take?

I didn’t want to make that film. NBK came to me as a story—I didn’t like the script. My wife at that time was pregnant with my second child. And I didn’t like the script. I didn’t actually want to make it. But I was married to Oliver so I’ll make anything he wants to do because that’s what you do… When that ended, I won’t tell you the whole thing, but it ended with her telling me I couldn’t make Natural Born Killers and I chose to make it. She told me she wanted to divorce me if I made it. And I made it anyway. Ended up divorcing her nine years later. That’s the real story.

You made it because of that relationship with Oliver?

No, that’s because of me. I made the choice to make the film. Oliver had nothing to do with it. I was going to make the film with Oliver no matter what. [My wife] telling me that I had to make a decision—I made the choice. Nothing to do with Oliver. I made that film, and that’s why I made that film. Why it looks the way it looks. Why it has the freedom of visuals. And why it also has, from my position, so much angst and anger attached to it visually. Because he was going through a divorce, Oliver was. I was about to have a divorce, and I just said, “fuck it!” It had more of me than it probably should have had. Normally I don’t put that much [of the] personal into something. I couldn’t sleep at night. I was a wreck. And I love Oliver. He was certainly one of the best directors of that time period, made the most influential films of that time period, politically speaking. And he made me realize the value of words in a script. I think it’s resonated with me until now.

You’re rare among contemporary cinematographers in that you operate your own films. It’s surprising to me that it’s so uncommon.

Why?

Samuel L. Jackson in The Hateful Eight (Quentin Tarantino, 2015)

It’s like calling yourself a screenwriter when you write an outline but then give it to someone else to fill in the dialogue.

I cannot imagine my shooting a film without operating the film. Because number one: I feel like, if I’m not shooting something with my eyes on the camera, I cannot see what the director wants. But more than that: I can’t see what the actor’s doing, I can’t see how they’re responding, I can’t see their eye contact. I want to look at an actor. I don’t want it on a monitor. You know, you have to do that at certain times on certain cameras, you can’t help it. You’re operating because you have to go remotely, especially in today’s age. But I much prefer to look through a camera and look at the eyes of an actor. The pearl of the eye. And to say to a director, that was great or not, I have to respond to acting capabilities.

Also: I want to move the camera as I see in my mind the aesthetics. I move a camera in the way the director and myself have come to agree with the assessment of what the picture should look like.

I wonder how you negotiate the precision of certain filmmakers—especially those who storyboard—with a responsiveness within the scene itself.

I make may exactly what they want—what Marty wants, or Oliver wants, or what Quentin wants—it’s still a contact of an eye piece to an actor. I don’t care how closely storyboarded—I’m gonna make the shot. It’s about the quality of creating for them exactly what they see in their minds. And then also having communication with them. Quentin doesn’t do playback—there’s no video on set. So with Quentin, he trusts me as an operator. And that’s pretty vital.

Nobody nowadays doesn’t do playback, other than Quentin. There’s no video house, no video rooms. You just watch it, select it, walk off. Nobody. Everyone goes back to the room, plays back the take they just saw, says yes or no. Most people choose not to make decisions based upon what they’re looking at. Because most people are in a village. A video village. And not good or bad, that can be to the advantage—if you’re not terribly secure and you’re able to see it back again, then that’s a wonderful aspect, because you can do it again. You may not have seen it — you’re watching a monitor. Some directors have the capability of being masters and others don’t. Doesn’t make them less or minor. People need it to see the work. Could you make 1917—can you watch that film without knowing what your playback is? No. You have to watch it.

Color correction must be hugely influential in this regard too.

It’s immense. If you go into digital intermediates, it’s different than grading by chemicals. Hateful Eight was all chemical. It took me back in time when I did it. The freedom of a digital release can take a DP who has very little talent to a DP who appears to have great talent. I can shoot bad shots and I can improve my shots. Immensely. Now that I shoot with digital intermediate, in my mind, I know I don’t have to deal with this, this, and this. That wall’s too bright, that color’s too green, this is too warm—whatever. I can shift it. I know and I’m aware, and it makes me more secure in moving more rapidly, but also with a greater level of confidence that my knowledge of digital intermediate is going to resolve issues I couldn’t contend with on set.

It’s another tool in the toolbox.

The more we get, the better we get.

Mick Jagger, Robert Richardson, and Martin Scorsese on the set of Shine a Light (Martin Scorsese, 2008)

On Shine a Light, you had some of the greatest cinematographers of our time operating for you: Robert Elswit, Ellen Kuras, Emmanuel Lubezki, John Toll… I’m curious about your relationships with fellow directors of photography.

I don’t talk with a lot of other cinematographers. I just don’t do it. Unfortunately. I love Chivo [Emmanuel Lubezki]—I talk to Chivo a fair amount, I talk to Ellen a fair amount. But we don’t talk about our projects or anything we’re doing—we just don’t do it. I don’t talk to Roger [Deakins]… I mean, I know them all. I don’t deal with them in a personal space. It’s odd. Do the Beatles talk to the Rolling Stones?

I can imagine many artists wouldn’t want to have other voices whispering in their ears.

I would love to have Chivo and Roger come to me and tell me how they do things. I would only benefit from their knowledge. Let’s arrange that—why don’t put that in the article that Bob Richardson would love to have Roger and Chivo come teach him how to shoot a movie. Because I’d love that, that’d be brilliant. They’re not the only ones. I’ll take a slew of fucking cinematographers. Put them in a room and teach me how to shoot, because I’ll only benefit from the level of knowledge that all these people have. Of course.

You can still feel that openness in your work, continuing to learn. What are you still excited about?

I do believe that I am a student. I’m constantly in desire of knowing more. I’d love to know high speed, like take me 96-frames per second, 48, whatever the number is. Ang Lee—he wanted to make a movie about Muhammad Ali, he wanted to do it in 96. Okay, I got it. I want to do it, teach me what it is to do that. Let me experiment with that. 48. Did it work? No, maybe it didn’t work—do you need to go to a higher speed? Can you move between speed and ramping in a film, to change the technical nature? Yes, you probably can. But it’s so precise you see every single hair. And wait, then you shift it to 24. Suddenly it’s more blurred in frames. What happens? I want to play with that world. Teach it to me. Let me change the movement of projectors, or televisions, or monitors, to shift so I can sell something. Why not different speeds? Why can’t you work 48, 96, 24, and each one gives you a different level of precision or lack of precision? It’s like shifting between the granular nature of Super-8 film stock to 65, or Imax. I’ll play. I’m just beginning. You may think I’m at the end, but I’m just beginning.

C. Mason Wells is curator, screenwriter, and head of theatrical sales for Kino Lorber.