Interview: Miko Revereza

All images from No Data Plan (Miko Revereza, 2019)

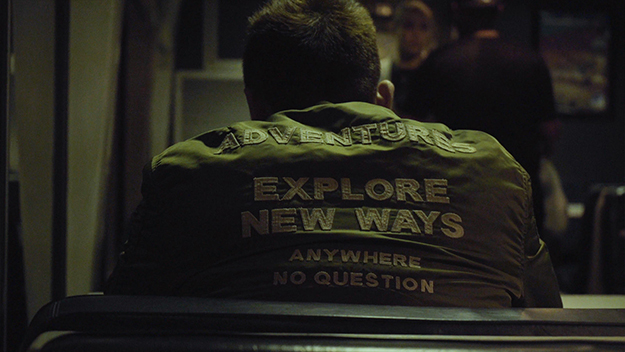

Shot on a cross-country train trip from Los Angeles to New York, Miko Revereza’s debut feature No Data Plan turns a familiar cinematic conceit into a conduit for personal reflection. Living in the U.S. illegally for over twenty years, the Filipino-born Revereza frames the three-day journey as a microcosm of the immigrant experience—its dangers, practicalities, and realities. As the film begins, Revereza is boarding an Amtrak at Los Angeles’s Union Station, his small digital camera capturing the mass of bodies as they funnel into the various compartments. Through subtitles, he speaks of his mother and how they communicate under threat of government surveillance: she has two phones, one for routine conversations (an “Obama phone”) and one with no data plan, which they use to speak about immigration-related issues. Proceeding to tell of his mother’s affair with a younger man (a thread that structures and runs throughout the film), he reflects matter-of-factly on his family life and the strange dynamic these circumstances have prompted. In a diary-like manner reminiscent of Chantal Akerman’s late digital films, Revereza shoots passing landscapes and incidental details with equal curiosity, intuitively capturing the rhythms and longueurs of long-distance train travel, as well as the anxieties of anonymous immigrants—anxieties conveyed in overheard phone calls, encounters with ticket takers, and eventually, the presence of Border Patrol officers. Quiet, contemplative, and legitimately brave, No Data Plan is that rarest of things: a personal film with real world consequences.

Following No Data Plan’s North American premiere at the True/False Film Festival, Revereza and I spoke about the film’s spontaneous inception, the sometimes messy emotions that influence the editing process, train travel, and “fugutivism” as it relates to the contemporary immigrant experience.

No Data Plan screens Friday, April 19 at Film Society of Lincoln Center as part of Art of the Real.

You mentioned in your introduction at True/False that you shot No Data Plan in three days. I’m curious about the conception of the film up to when you started filming and if it changed at all once you began? Had you always planned to shoot only for the duration of the train trip, or did that idea develop along the way?

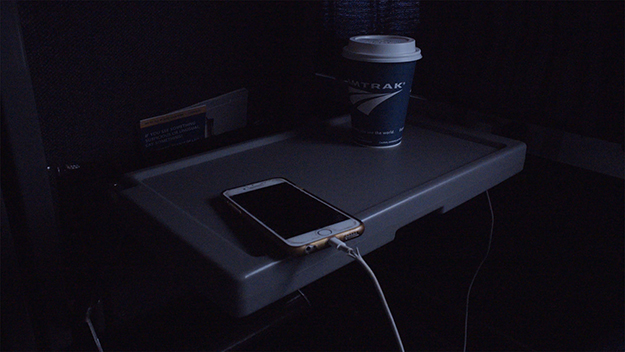

This train ride across the country was not my first time. The previous year I did the same trip and shot a little bit and sat on the footage and nothing came out of it. This year I didn’t really have any expectations to shoot again but had my camera by my side anyway. When I bought the Amtrak tickets I swear it said on the website that there would be WiFi onboard, but when I got on the train I was extremely disappointed to find this was not the case. I had recently cancelled my iPhone’s data plan because of increased anxiety over ICE and Border Patrol data monitoring of immigrants. I realized I just stepped into this three-day train ride with no WiFi, with a phone with no data plan, and with nothing else to really pass the time, so I ended up spending most of it shooting. But even shooting majestic open landscapes quickly became boring since I had seen it all the prior year. I felt my eyes were constantly searching for new details to shoot: water residue on the window, scratches on the glass, hand prints, light moving through the train’s interior, stuff like that. I was completely unaware I was shooting my first feature film or that this three-day train-ride would be a standalone film. I thought that I was collecting footage like one usually does in a diaristic film practice. It wasn’t until after Buffalo, New York, when Border Patrol boarded the train towards the end of my ride and when I was reviewing all the clips on my camera, that I thought I might have something contained within the train ride. I was completely shook up in that moment and was so aware of how my body moving through this space with nervous shaky hands achieved a singularity with the camera movement. This film came out of very real conditions of statelessness and fugutivism, boredom and confinement—micro-personal nuances of the undocumented experience that aren’t visible or represented in media. The edit stayed mostly chronological so it very easy to cut together. I wanted to finish the film immediately. There was no refining. I wanted the edit to remain within the time frame and mind state that I was in shortly after getting off the train when you still feel like you’re moving.

At what point did you decide to use your mother’s personal history as a thread throughout the film? Was there any hesitation on your part?

This was writing I had on hand—something I was working on for the past year as the events were developing in my family. At some point in the editing process I dropped the story in there just to see. I liked it and left it there as a placeholder for my voiceover. This never worked because the sound of my voice and thick industrial train sounds would clash. I found that by leaving out the spoken voice it left room for the viewer to hear their own voice—like how thoughts are spoken silently in our heads over the sounds of our environment. I like to think that this opens up the subtitles to the internalized language of the viewer.

My family is very supportive and proud that my films and my words are reaching people. I think to engage with any artists at risk from state sanctioned violence, it’s not just about survival—wellness extends to the ability to thrive as a human being in a system constructed for our disappearance. To sit still, to be silent and hide indoors is a risk in itself.

Can you tell me a bit about the shooting process? As far as compiling footage, did you find yourself constantly filming, or did you have to consciously negotiate time and space with regards to either locations/landscapes you were hoping to capture, or even with regard to other passengers?

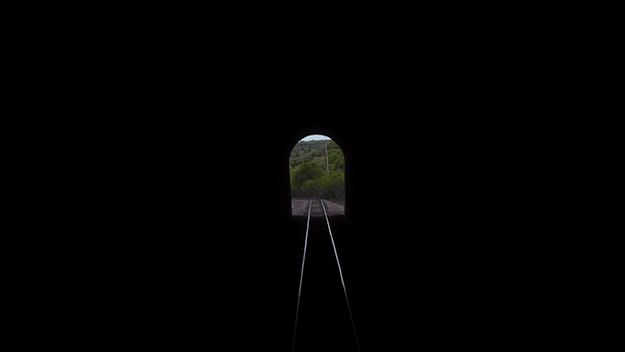

I shot this on a Sony a7S. I guess that’s my go-to camera. As far as compiling footage, I would just sit there until something would catch my eye. I start shooting in a general direction and hold a shot to let things unfold, things like people crossing the frame or shipping containers passing by outside. The thing with train travel is that it’s really difficult to get more than two hours of sleep at a time. I would be awake at odd hours and catch the sunrise, or miss parts of the day when I was napping. You can also walk up and down the train, watch the tracks from the rear window—there are so many different seats and vantage points. It’s quite a lot to explore just within the interior of the train. There were certain points I was looking forward to, like the long tunnel between New Mexico and Colorado, and sunrise in Kansas. After Chicago, I didn’t even want to touch my camera anymore and was so over it—I felt like fast-forwarding through Indiana, Ohio, and Pennsylvania.

As far as editing, you mentioned that it was quick and chronological, but how did you approach the footage as far as structure and pacing? There’s a rhythmic feel to the film that’s appealing. I also like that you not only explore the compartments but also make plenty of time for moments outside the train, by the tracks or at various stations.

I approached the editing first by laying out all my selects in chronological and geographical order, and from there it was more or less a process of finding lyricism and emotion in the rhythm. Seeing how long to hold to really feel a sense of loneliness, boredom, and alienation, then seeing what moment connects intimately to the next shot. It’s a film about traversing geography and being implicated by the separations of a bordered society. It’s also interesting to think about reversing the great American “headed west” road trip narrative.

Looking back, I think my mandate towards editing this film was to make sure it conveys human touch and timing. The separations of territory can be mended by creating new connections. How our eyes and ears reassemble space—I was just reacting to my gut feeling of where to cut, when I feel that one space connects to another. I think that’s why it came together so fast, like only five weeks of editing or something. I felt that to draw out the possibly infinite refinement of editing could drain the intensity of that affair. Emotion drives the edit and our emotions are messy. So I don’t believe in a seamless and invisible edit. It had to retain its awkwardness and discomfort.

It was also a priority to retain the feeling of movement—like really feeling like the train is pulling away from something or the gravity and weight of shipping containers passing by or sinking into a dark tunnel. To really feel those moments, they kind of have to catch you off guard.

Can you talk a bit about the idea of train travel as it relates to the immigrant experience? For many in America train travel has almost romantic connotations, but for others it’s a necessary and still frequent form of travel.

The train and bus are modes of transportation for many people who don’t have the proper documents to fly. My DACA and California driver’s license were both expired so I was technically out of status. I think I forgot to mention that this is the reason why I took the train in the first place. This is why ICE and Border Patrol target trains and busses.

I do feel a sense of nostalgia for the “great American road trip novel/movie/whatever,” but I also wonder about that model and who gets to travel freely and adventurously across the United States like that. Train tickets are actually more expensive than flying, so people on the train really have specific reasons why they’re traveling this way. I’ve met people who were just released from prison, people who are in some form homeless, people trying to escape addiction, people looking for a new start in a different place. On the train, everyone is telling their neighbor their life story. You get to see what modern fugutivism looks like and how mundane it looks. Train travel is not romantic at all. Spending just three days on the train you get a sense of how tragic America can be.

We travel along the same arteries as the constant flow of commodities—countless shipping containers in passing: lumber, coal, crude oil, ethanol, soap, corn, wheat, rice, French fries, canned goods, pharmaceuticals, frozen chicken, salt, sugar, phosphate, sulfur ammonia, steel, gravel, crushed stone, plastics, glass, clothing, footwear, electronics, and auto parts. It’s really humbling to feel dwarfed by this constant flow of commodities and to meet people who are broken by a capitalist system or implicated by a penitentiary system.

I didn’t make the film about them. It would be endless if I did. Instead I wanted to relate my family’s struggle and the heartbreaking realization of what American Dream they had envisioned before coming here and what it had turned out to be. There is a voice in the film right before Chicago that said something so poignant about how we experience America. She said something like “Well hey, if we make it, then God bless America! If not… SHIT!”

You establish this tension right away when the ticket taker comes by and you overhear her asking a passenger for their ID. And then later the threat becomes very real when you spot the Border Patrol vehicles and they proceed to search the train. Can you describe how traveling and being targeted in general has changed for you over the years? You mention in the film that you’ve become programmed to recognize Border Patrol SUVs and undercover officers.

My first cross-country trip was when I was 19, on a Greyhound bus from Oakland to New York City to check out a portfolio day at Cooper Union—three to four days both ways. I remember I was on the bus pulling into Denver when they announced Obama had won the 2008 Presidential election. A few years later I spontaneously got in a car with friends heading to Marfa during the height of Arizona SB 1070. It was such a dumb idea and there were at least five border patrol checkpoints we drove through where I pretended I was sleeping. Luckily for me I was in a car full of white dudes who got the simple go-ahead when other cars had to present all their passengers’ IDs.

Even from the comfort of our apartments we are targeted. Beyond the doorstep, the monitoring of social media of immigrants and IP addresses and locations services gives ICE enough data to know when someone is arriving home from work so they can intercept them in their drive way. Based on very recent high profile detainments like 21 Savage and Claudio Rojas it seems that ICE and Border Patrol are actually targeting people who are speaking out against them and have a sizable voice in their communities. Perhaps this makes my practice of filmmaking—with the goal of circulating these images at festivals and receiving press about it all—pretty risky. I feel like in the post–9/11 era the “border zone” has expanded to swallow the entire country, and so has the dragnet of immigration enforcement. With that, the rise of privatized immigration detention and companies like GEO Group who lobbied for Trump. When they got quotas for your capture and have you cornered in a seemingly impossible bureaucratic trap, it makes me feel like I have nothing to lose and might as well put myself out there—put my story and subjectivity out there to see. Because if we undocumented immigrants don’t make our own films, then someone else will extract them from us. I’d say that this sense of precarity has shaped me into who I am, how I navigate the world and cultural institutions, and what I value and aspire towards in life: free human movement.

It shouldn’t be this complicated for people to get around when we can get cat litter delivered to our doorsteps in two days. I haven’t been back to the Philippines in 26 years and have come to understand the world in relation to what is exiled. I’ve learned to navigate this country in relation to what I am systematically excluded from. Growing up, it was a driver’s license, an ID, a social security number, legal employment. Even in the art and film world they often require citizenship or permanent residency for institutional support. Why are we reproducing our borders in how grants are administered? I made this film with zero budget in three days with no crew and, if anything, growing up within these circumstances has taught me how to pull shit like that off. How to hack the system. How to circumvent the structural borders working against me. How to infiltrate the cultural institution and how to be slick enough to keep dodging ICE and Border Patrol.

One of the most quietly heartbreaking moments in the film is when you quote your mom as saying: “I just wish I could do that too,” in response to your suggestion that you might leave the U.S. Is that still the plan?

Yes, it’s a plan in motion. I have a few opportunities abroad and it’s very likely that I will be leaving this year. Upon that departure, it’s likely that I will be banned from the U.S. for 10 years. That is one of the inhumane punishments of overstaying a visa. But the way I see it is, I am trading access to the U.S.—which has excluded me my whole life—for access to the rest of the world. I can finally attend film festivals with my film. I can finally revisit the Philippines. Why that line is so heartbreaking is because this decision would exile me from my family, friends, and place where I grew up. It’s also heartbreaking to compare circumstances with my own family and recognize the privilege that I’ve managed to accumulate for myself from being a cultural producer. However, for me to move further beyond these transgressions of the U.S. border means for me that I must transgress the border itself. It’s my life work as someone who makes moving images to exercise the right to free human movement.

Jordan Cronk is a critic and programmer based in Los Angeles. He runs Acropolis Cinema, a screening series for experimental and undistributed films, and is co-director of the Locarno in Los Angeles film festival.