Interview: Mark Jenkin

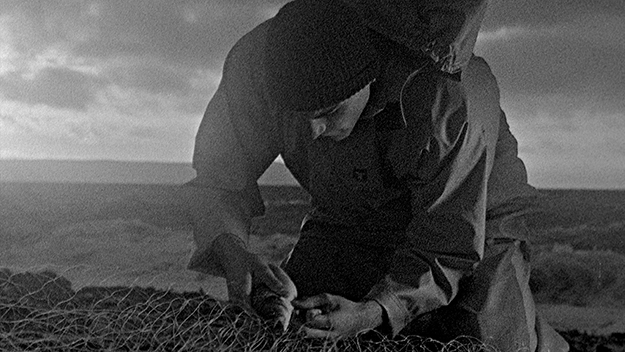

Mark Jenkin finds a muse in his home county of Cornwall: from stories of youthful outsiders (Golden Burn, 2002) and fragmented families (The Midnight Drives, 2007) on through his documentary work (The Lobsterman, 2001, on Cornish playwright Nick Darke), his cinema keenly captures the ways in which tourism has displaced and reconfigured working-class communities in coastal Britain. These tensions boil over in Bait, in which the protagonist, a fisherman named Martin, palpably bristles with resentment towards the vacationing Londoners who have purchased his childhood home and pushed him out to the margins of his town. At the same time, he faces the urgency of saving enough money to purchase a new boat; his brother, Steven, has taken their shared vessel for himself to give summer harbor tours to partying, drunken rave kids. Turning away from Steven on principle, Martin scrapes together spare pounds and pence in an old cookie tin; to barely break even, he fishes by hand with help from his nephew, painstakingly laying out enormous nets on the shore that yield piecemeal catches.

Shot in black-and-white and on 16mm, the film’s sharp lines and aesthetic austerity isolate Martin within the hardness of manual routine. But Jenkin also animates Martin’s psychological intensity through hyperreal sound design—a percussive accent registers as though underwater—and disjointed montage, evoking the post-traumatic dread of Nicolas Roeg. Although it’s Jenkin’s fifth feature, Bait is his most sustained engagement with a 13-bullet filmmaking manifesto he drew up for his mid-length film Bronco’s House (2015). Aesthetic guidelines—to shoot in black-and-white, and contain no non-diegetic music—collide with conceptual attitudes—to subvert or ignore genre constraints, to realize the project “with a minimum of fuss,” and to break at least one of the 13 rules. Developed by hand in an antique Bakelite rewind tank, Bait’s film stock pops with irregularities and splotches that infuse the story with a weathered quality, while also emphasizing the medium’s materiality and mortality. It’s a fitting texture for a story about a fisherman combating the shifting times and tenaciously clinging to a life under threat of erosion.

In advance of Bait’s North American premiere at New Directors/New Films, Film Comment spoke with Jenkin about the gray areas within the film’s class conflict, the advantages of technical limitations, and the nonverbal secrets of cinematic rhythm.

I was drawn in by how stylistically and formally dynamic Bait is, but at the same time, the story is so pared down that it almost feels archetypal—the dynamic between the two brothers feels like a modern myth. How did the story come to you, since form and content are so intertwined? Did one come first, or did one influence the other?

I wrote the first draft about 20 years ago, and it started out as a found footage film. The idea was that the brother had an affair with a rich holiday-maker who’d come down to stay—she was pregnant, and he’d written himself out of this unborn child’s life, so he was going to make a video diary that, one day, the child might want to watch to find out who their dad was. In that case, this little video camera was going to end up being this catalyst: he would go around the village with this camera, and the issues that are at the heart of the film—even now—would then explode. It went through various incarnations until 2014, when I went back to shooting on film for Bronco’s House, which was a 45-minute film shot on a Bolex, hand-processed, and post-synced. I realized that, actually, I wanted to make a feature film using that same form, so I looked around and found this old project that had fallen by the wayside. It’s the most unlikely project to be done in this way, a found footage film, but I thought that was a good challenge. So I rewrote it based on how I would shoot it, and I think that’s where your point becomes very relevant. It did become a much simpler and archetypal story, because in terms of the plot, it had to be broader. The idiosyncrasies and the randomness and the complicated way that life pans out are what makes [found footage] films so interesting, but to make something more formally distinct, I did have to go back to using archetypes—where people are conduits for points of view and ideas.

You mention going back to film when you made Bronco’s House—you drew up the “Silent Landscape Dancing Grain 13 Manifesto” around this point. What inspired you to go back and create this framework for yourself, and what have you learned working within constraints like that?

I made a film in 2011 [Happy Christmas] which was entirely improvised. There were two things I realized when I finished it: one, I wasn’t particularly happy with the aesthetic, because the camera had been making aesthetic decisions that I had no control over. I felt that this camera was this little computer that was getting between me and the actors—it was sort of autonomous, which sounds a bit ridiculous, but I didn’t feel that the camera was necessarily on our side during the making of the film. The other thing was that there was so much editing—we shot digitally, so we shot 100 hours of footage—and a lot of it was problem-solving. And I know a lot of films are made in the edit, but I like to think of it as a creative process rather than a damage-limitation process, which it happened to be here.

After that, I got ill and had to have an emergency operation, which meant that I was laid up on the sofa for about three months. I watched the Mark Cousins documentary, the 15-hour The Story of Film, twice. I had to sleep a lot, so I was kind of in the dream state listening to Mark Cousins’s theories about cinema. I realized that I’d fallen out of love with filmmaking a little bit: I retraced my steps to where I first fell in love with making films, and it was when I was a teenager, with a Super 8 camera, and I’d save up to buy a single roll of film. I would be really careful about what I would film—I would look at things through the viewfinder, but I wouldn’t film things until I was absolutely sure. This was around the point when someone had decided that film was dead forever and the industry had moved on. It paradoxically became very easy to find out how to work with film in a handmade sense, because the knowledge didn’t have a financial value anymore so the secret could be given away. I’d always hand-processed photographs before—how difficult could it be to hand-process my own 8mm and 16mm film? I realized how achievable it is, and how rewarding it is, to be involved with the alchemy of creating images in front of your very eyes.

What I wasn’t expecting was how much it was going to influence the way that I was making stuff. What I was really in need of wasn’t the tactility, or the aesthetic, but it was actually the limitations that film ensured that I worked within. If I had shot the same way on film as digitally, I’d have been bankrupt within five minutes, so it was a practical manifesto rather than a political or artistic one.

At the same time, the hand-crafted way that the film is processed emphasizes the film’s tactile details. You’re rooted in close-ups of hands, and boots—you see a hand becoming a fist, and you think of the capability of that hand, and its daily routines. What was your approach to crafting this visceral atmosphere?

I shoot with a manual clockwork Bolex 16mm camera, and I have to physically hold the shutter down. I’ve got two choices for what I can do with the other hand: I can either pan or tilt the camera, or I can focus pull. So this aesthetic was borne out of what I could do with that camera, and its limitations. A lot of the close-up work is something I always do because I don’t shoot any coverage. I always shoot feet to cover myself for transitions, but you can also tell a lot about the characters by looking at what shoes they’re wearing and what their feet are doing. You’ve got this stark contrast between leisure and industry that runs through the film: delicate shoes or trainers are always up against working boots. Hands as well. The working hand. The blue-collar and the white-collar hand, effectively. You can say so much more with an image rather than any expositional dialogue. Whether I’m reverse-engineering meaning into those shots, or whether that was always there and I just wasn’t conscious of it, it’s still really important to me.

The really key thing is that I shoot 100-foot rolls of film, so I load everything into the camera when we’re out and about filming, so the beginning of each roll is flooded with daylight. To get to the point where it’s usable, I normally fire off a few feet of film of whatever’s nearby, so I end up with a random close-up. In the edit, I know it will have some relevance because it’s there in the scene; it’s part of that place, or it’s part of that person. An example of that is in the pub, where you’ve got the figureheads and the busts from all the maritime ships. I didn’t even see any of those carvings when we recced [scouted] the location. It wasn’t until I was set up for a dialogue shot that I thought, Right, I’ve got a few feet to fire off, what can I shoot? Let’s spin the camera ’round. There’d be a carved woman’s face staring at me, and suddenly, that’s now in the edit, and quite a big part of those scenes. So a lot of it’s borne out of those limitations. If I was shooting digitally and I didn’t have those constraints, I never would have considered those close-ups, those cutaways.

And then you’re in the editing room, looking at what you have for a particular setting—or even ways you can navigate across settings to build out that world.

Yeah, and normally I have a real stark difference of footage: I’ve got one set of footage that’s the script exactly as it’s written, and then I’ve got this other bin of footage that is quite often just batshit crazy stuff. I might go a few months of the edit ignoring a shot, and then sometimes I’ll have a scene that doesn’t quite work, and then I’ll go, “Oh, hold on, I’ve got a shot here of a bird flying,” or somebody’s foot walking, or a random bit of slow motion. Suddenly that makes everything hang together.

What is it about creating these dislocations in the edit that comes naturally to you?

I think it’s the potential of film. I just love what you can do with pictures and sounds: the excitement of thinking, “What happens if I flash-forward half an hour in the timeline? What happens if I jump the sound back an hour earlier, but leave the visuals in the present tense?” We haven’t got another art form where you can evoke that sense of geographical and temporal dislocation in the same moment. Because the film’s in black-and-white and it’s sort of a kitchen-sink drama, people keep asking me about realism. I find it really difficult to talk about, because it’s got certain connotations in cinema: what realism is, and what social realism is, for example. But actually, realism is reality, and what the hell is reality? That idea of being able to jump around—like our nonlinear consciousness does—that’s how the film becomes representative of me, or of a certain type of humanity above and away from the story that’s going on in the film. Which I hope is what people are connecting with as much as the nuts and bolts of the story.

The other day, somebody said to me, “When it comes down to it, at the end of the day, it’s got to be about story”—which I do agree with, but I think when people hear that, a lot of the time they also say that the film is really about the script. I couldn’t disagree more with that sentiment. We have so many decisions that are made at script level, so many conversations about script development. After that, you can have a 10-minute conversation before you’re about to shoot about what it’s going to look and sound like. We’re working in an art form that is 120 years old, and we already seem to have given up on the discussion of what the form should be. It’s kind of desperate, and I think it’s really bad in this country. The conversation about form in Britain is pushed to the margins, it’s pushed out to where people are working in so-called experimental film. Certainly a lot of my short film work gets put into that experimental category. I don’t really know anybody who works in experimental film who would describe themselves as experimental filmmakers—they’re just filmmakers who feel the need, or even maybe a responsibility, if that doesn’t sound too grandiose, to be experimenting with this very youthful form.

You’ve made several films looking at different aspects of Cornwall, and tourism, and class conflict. As time passes, how do you see your relationship to those ideas developing? And how do you see the place changing as well?

What I’ve really seen is—it might be a change within me, thinking that I’m making films that are concerned with a local issue where I live and in a place that I understand, to now being something that seems to be… certainly national, in this country. But also quite internationally relevant: that gap between the haves and the have-nots, as they say. I heard someone recently say the haves and the have-yachts, which I thought was a nice expression as well. But that’s sort of the main argument that is linked to everything in this moment, certainly in this country. It’s something I really empathize with, and I’d absolutely agree that the gap between the haves and the have-nots is getting bigger and bigger, but also if you do keep talking about it in those simple terms, you’re not really going to get anywhere.

What I like about the reaction to Bait is that the early reviews have discussed the gray area that the film exists in. Which surprised me a little—I thought people might say that it was too simplistic, and that you’ve got outsiders against insiders, which I never intended it to be. I thought that if people needed to write something very quickly about it that maybe that would be how it was perceived, but I think I underestimated the audience it’s had so far. They’ve certainly picked up on the fact that these issues are incredibly complicated. When the film comes out later in the year here in Cornwall, I wonder what the reaction will be. Because it’s not simple: people aren’t one thing or the other. For example, you’ve got this huge housing problem with holiday homes and second homes, and a lot of the communities around here are like ghost towns. But I also know people whose livings are made through working on these empty holiday homes. You can criticize the idea of it, and the theory behind it all, but actually the the logistics and the practicalities of the issues are incredibly complicated.

Could you talk a little bit about how you developed these complexities through the different generations of characters, particularly the younger characters?

I wanted the film to be hopeful, and the way to give it a bit of hope is in the way that you portray those younger characters. Actually, the Romeo and Juliet couple at the heart of it are two who are the most unaffected by what’s going on, partly because they don’t have any responsibilities at that age and they don’t have to be involved with it. I’d always wanted Katie, who’s the daughter of the second homeowners, to be a really likable character, and faultless in a lot of ways—blind to any of the issues that were going on, and above it all on a human level. Partly because the tragedy would be more powerful, but also just so that there is a bit of hope that as time goes on, things will change, and there will be a certain amount of empathy between the different warring factions in a community like that.

Even the son [of the second homeowners], who within the world of the film, doesn’t really have many redeeming features on the outside—he’s just a product of his upbringing. I think at the beginning, you can see that he’s going to turn into his dad. But maybe the events of the film could change the course of his life. Maybe he’ll become somebody who’s less obnoxious, or less entitled. I wanted all of those flaws in the adults—who’ve all kind of gotten to that point where you think you’re on their side, but then they’ll do something where they blow it—I wanted all of that to be absent from the younger characters. I wanted them to be more honest: they’re not really playing characters, they’re being real to themselves, either as a bit of an idiot, or an innocent, or kindhearted, or whatever it is.

And this idea of the passage of time is also more nuanced through Martin’s nephew, who starts working with him—sort of feeling drawn back to the way of life that his father and his uncle lived, even if it doesn’t quite apply in the same way. I found that relationship really touching.

It is a funny one: you think, it’s great that he wants to follow his uncle, but then if you take a step back and look at what his uncle has to do to make a living, maybe the dad is right. And the dad probably is right. But you can’t help thinking that if somebody wants to go that way, you’ve got to let them do it. Actually, if they live a hand-to-mouth existence, and the next generation do, and the next generation do, and gradually things improve, then maybe it’s worth taking that step.

Exactly. These dynamics come to a head at the climactic scene when Martin comes into the bar with the lobster trap, which you integrate alongside two dinner scenes—could you elaborate on that sequence?

I originally wrote this as separate scenes, but I knew that they would cross-cut because it was the climax of all of those storylines. You’ve got the mending of the lobster pot in the bar, you’ve got this very middle-class meal going on by candlelight, and then you’ve got this working-class meal of pasta in a kitchen in a council house. All of these three elements working together. And also taking most of the audio out. You had this excruciating silence that was relieved at certain points, but I knew that if people were watching it in a cinema, that there would be collective anxiety of there not being any sound.

The first time this cross-cutting happens in the film is when Martin is having a conversation at the pub, and then the three teenagers are having an argument around the pool table which is totally inconsequential. It’s the whole backstory of how Martin’s brother’s wife was dead, and I was thinking about how I could keep this heavy exposition without people noticing that they’re being explained to. You’re trying to keep up with what’s going on, but you didn’t really need to know who was saying what—it’s about energy rather than the specifics of what’s being said.

That’s the thing: you could write and redraft that on the page over and over again—cut to, cut to, cut to—but until you’re seeing it and hearing it, you don’t know what you’re dealing with, because it’s all about the feel and the rhythm. To me, that’s real filmmaking: when a script cannot help you. When you’re writing a novel, you could write that scene. But you can’t write it in a script.

You’ve mentioned that you’re interested in finding spirituality in cinema even if it’s not overt in the narrative—was that something you were thinking of for this story? Some of the close-ups of hands and exchanges of currency recall Bresson.

I like the otherness that you can create in the atmosphere with film. That sort of transcendental element, where things just live and you can’t really pick it apart, or you can’t really figure out why that shot cutting to that shot with that audio suddenly creates this feeling. I’m really interested in that. I’m not interested in understanding it, because I think if you can understand how it’s working, then it’s probably not working anymore.

Somebody said to me that my films feel like horror films without any horror: this sense of otherness. I suppose that is built up partly through the abstraction of the aesthetic, because there’s a timelessness to it. At times it can feel ancient, but if the design or the plot or the characters are very modern, suddenly they create some kind of complexity that is very difficult to get a handle on. But I think also that idea of jumping around in time and space creates this otherness, that sense that the film form is something in its own right. It’s not an invisible thing that’s there just to communicate a story—a lot of films can be like filmed theater, where the actors are given their actions and the camera stands back and observes it. Horror quite often draws attention to the form: a jump scare relies on an edit, and by default, you are then drawing attention to that edit. I’m doing that all the time; I like acknowledging the form. If that can be achieved in a way that isn’t just about the form, then it creates something that’s sort of other to the character in the story. It’s not a faith thing or anything, just a sense that there’s something intangible and unexplainable. And magic, I suppose, which I think goes back to my earliest interest in shooting on Super-8. The magic of seeing an image appear on a piece of plastic that you’ve seen go through a camera.

Since you mention returning to what got you interested in film at an early age, is there anything that you’re really itching to try next, formally or narratively? Are you working on anything now?

I’m actually going to do a horror film next. After people said that my films feel like these horror films without any horror, I thought I’d try and make a horror film that does have some horror in it. But actually, the script that I’ve written is not outright horror—although it’s probably got a lot more horror than what is in Bait—but it’s easier to pitch to people this way. Before, it was like, “I’m making this film called Bait,” and people would ask what it was about, and I’d say, “It’s about fishing, but it’s not really about fishing,” or, “It’s about class, but…” Now I can say that I’m making a horror film set on an island just off the coast of Cornwall, a female single-hander. It’ll be made in the same way, but with a slightly bigger budget, slightly more ambitious in terms of the set pieces, and I’m going to shoot it in color. But it’ll still be 16mm, and still handmade.

Chloe Lizotte writes on film and music for Reverse Shot, Screen Slate, and the Los Angeles Review of Books. She lives in New York.