Interview: Mario Adorf

Mario Adorf has had one of the most deliriously diverse careers of anyone in pictures. Born in Switzerland of mixed Italian and German parentage, he has at various times he has worked in Berlin, Rome, and Hollywood, in commercial films and in austere art-house work. He has played character parts and leads, comedy and tragedy, and in recent years, as a stout, snowy-bearded patriarch, has become the quintessential grand old man of German movies and television, probably best known as the titular Italian restaurateur in Rossini (1997) or the nouveau riche sleaze in TV series Kir Royal (1986; a Deutsch friend called him the “German Sean Connery”). But well before this, Adorf had already worked with a staggering array of filmmakers, including Robert Siodmak, Gerd Oswald, Sam Peckinpah, Antonio Pietrangeli, Valerio Zurlini, Dino Risi, Dario Argento, Jerzy Skolimowski, Liliana Cavani, Fernando Di Leo, Volker Schlöndorff, R.W. Fassbinder, Straub and Huillet—believe it or not, I am not making this list up—building a body of ineffable, sometimes rattlingly eccentric performances.

While Adorf, 85, was in Locarno last year to receive recognition for his daunting life’s work, Film Comment sat down with him to survey his extraordinary career. It wasn’t quite possible to cover everything, but goodness knows we tried.

The Devil Strikes at Night

Your career arc is such an incredible and strange one, I’m not sure where to begin. Could you start by telling me a little about how you started out?

I was not an ambitious boy, let’s say. I never really had the idea to become an actor as a student. Only when I did my university studies, I got in touch with the student theater group. And there, I started not as an actor, but designing posters or sets and so forth, painting sets, and slowly I got small parts. Then, later, I went to Zurich and there in the theater I used to take part as an extra on stage, and there I met all these wonderful actors who were immigrants from Germany, mostly Jews, and that was, I think, the first time I had the idea to become an actor. And then I went to Munich, the academy, and started very early my first year, in a very successful film. And after two years I met Robert Siodmak. I think he is known to a cinephile audience in America. The most famous film he did was, I think, The Spiral Staircase.

Spiral Staircase and Criss Cross—these are classics of noir, but what a lot of even that audience doesn’t know is this other part of his career when he comes back to Germany.

He gave me this important part of this mass murderer, this serial killer, Bruno Luedke, who was considered to be the most terrible serial murder during the period between 1924 and 1943. And he gave me this part, and it was very successful and it was the beginning of a career that I made for myself in Germany especially.

How did you come to meet Siodmak?

He writes in his book that he saw me on stage in the play 12 Angry Men. I played the court stenographer. I had this idea for how to get people to look at this character, who sat there for two hours or three hours not really doing anything, by using tricks. He said he had seen me there, and then one night he asked me to meet him in a bar where the actors usually went in Munich. A friend of mine was the writer of the script, he asked me if I would pass by and meet Siodmak. But, I was performing in The Rainmaker onstage and played the beautiful part of Jimmy, and that very night I had an accident and tore my calf muscle, and had to go to the clinic, and came an hour late to the bar.

Finally I got there, I met Siodmak. He said, “Give me a bad look.” And I tried to look really mean, to give a mean look. He said, “That’s not really mean. Do it better.” I tried to give him more, a whole Peter Lorre thing. He said, “No, that’s not really mean.” Then he tore off his glasses and showed me [making ghoulish face], and said, “This is a bad look.” But I couldn’t do it. And I thought I didn’t get the part. Then he said, “Hey, what did you do to your leg?” I told him I tore a muscle in my right calf, and he said, “Oh, can I see?” He looked at it and said, “They don’t know anything, these doctors. Come with me.” And he took me to his hotel, the Four Seasons in Munich, to his room, and took a big doctor’s bag. And it was full of medicine and bandages and instruments, and he took out this spray thing, and he said, “This is a new invention from the States.” Today everybody knows this kind of ice spray, all of the football players use it. And he cut off my bandage and sprayed my calf. Then he said, “Now walk on it. Does it still hurt?” I lied and said no. We went back to the bar, and they asked Robert where he had been and he said, “I healed my Devil. I healed him. And he will play the Devil in my film.” He said, “Come on, show them, give them your mean look!” And he said, “You see how really bad he can look?” And so I got the part.

What was the research process like for preparing to play Luedke?

I had the possibility to listen to a tape of his voice, which I followed in having to learn to speak with a Berlin accent, and was also able to look at the drawings that he used to make in jail, simple figures with great big teeth, which a psychologist would say indicates a violent man that could well be a killer.

Il delitto Matteotti

Was the role of Luedke the one that you consider your breakthrough?

I had done before some very small parts playing the funny character in a German soldier story set during the war that was very, very successful [08/15, in 1954], but this was the breakthrough with getting awards. It had an Oscar nomination. The funny thing about that is that at the time the nomination for the Academy Award was not a big thing. I hadn’t even known about it, only three months after the Oscars somebody told me about it. Today it’s a big thing, but at the time it was not so.

You mention you had done small comic roles before, and this is a pattern that starts to emerge in your career through the ’60s, where you’re dividing your time between villains and comic relief, or little character parts.

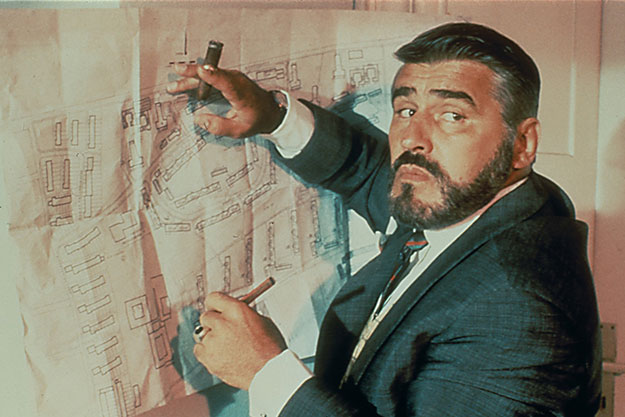

On stage I did comedy, I loved to play comedy. And I did not think I was typecast as the villain, because I always did other pictures, for example The Death Ship (Das Totenschiff, 1959), a famous novel by B. Traven, the guy who wrote The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, a movie where I played a very sympathetic character. But there were many villains or Mafiosi, in Italy especially. The most terrible villain was Mussolini, I played Mussolini [in Florestano Vancini’s Il delitto Matteotti (1973)], and that was something special, as a German—I’m half-Italian, but I did not at the time really speak Italian. But I was cast as Mussolini, and many journalists said I was the best film Mussolini of all time.

That’s some kind of distinction. Another director that you worked with who, like Siodmak, was somebody who had worked in the States and then returned to Europe, is Gerd Oswald. You did two films together?

Yes, two films. One was The Day It Rained [1959], which is showing here tomorrow night—I think not a masterpiece. But the second one, Brainwashed [1960], based on the Stefan Zweig story, this was quite an interesting story. I played a chess champion of the world, Centowic. Also a very mean character, but a very interesting character. I think it was quite a good film, even if they changed the story from the novel a bit too much for my taste.

Oswald has a mini-cult following for some of his American films like, A Kiss Before Dying. What was his directorial demeanor like?

He was the son of [German film director] Richard Oswald, and the family emigrated in 1938 or so, and they went to London. After my second film with him I met him in London. We arrived in London late, past midnight, and we had no hotel. So he said the only chance we had was to go to his father’s club on Piccadilly Road, though he said, “I don’t know if they still know me, but we’ll see if we can get a room there to pass the night.” And we rang the door in the dark, and a man opened, and he saw Gerd Oswald who was there in ’38, now it was 1960, so many years later. And he took one look at Gerd Oswald and he said, “Welcome home, Mr. Oswald.”

He was a very nice man. And I met up with him later in the States, when I got to Los Angeles. There—it was very funny—he was doing a television series called The Outer Limits, and one of the stars of the shows he did was Nick Adams, who was famous for a series called The Rebel. Nick Adams at the time was the chairman of the Screen Actors Guild. When I arrived in Los Angeles, the very next morning a trade paper, the Daily Variety, was slipped under my door with an article circled in red that said, “Nick Adams Blasts Hun Actor.” It was me—the Hun actor. I was then, at the time, cast as Mexican, Sergeant Gomez, in Peckinpah’s picture Major Dundee. I was not a blonde Hun, but in The Devils Strikes at Night I was blond, so Nick Adams might have seen that and said, “Why does a German blond actor come to play a Mexican in Peckinpah’s picture? We have so many Mexican actors out of work, why does he get this part?” So I gave Gerd Oswald a photograph of mine in which I was made up as a Mexican, and signed it “To Nick, The Rebel, from Mario the Hun.” But Oswald, he was very kind to me, and helped me a lot to feel myself at home in Los Angeles.

And you had come out to California specifically for Major Dundee?

Yes.

How did that role come about?

One of the big agents at the time was Paul Kohner, he was a German [Austrian] Jew who had come to the States even before the Nazis I think. He was an important person at Universal and he became then an agent, he had all these people like Billy Wilder, John Huston, William Wyler, and then stars like Ingrid Bergman and Max von Sydow. He was a big agent on Sunset Boulevard, but I met him in Germany where he had friends. He said, “Why don’t you come to the States? I invite you.” So I made my first trip in 1960 or so. And there I met Billy Wilder. He offered me one of the Russian characters in One, Two, Three [1961]. Then, finally, when it came time to shoot the film a year later, he offered me the role of the third Russian, the Russian who had nothing to say, and I said, “No,” I said, “Sorry, Mr. Wilder, not for me.” So I turned it down.

Then, 16 years later, Billy Wilder asked me to do a part in Fedora. And when I met him I thought he had forgotten that I had turned him down before. But when we entered the hotel in Munich, he entered in this kind of turning door, passed by me and said: “And this time, don’t turn me down.” And so he had me for this part, which was not a big part anyhow, but I liked working with him and it was wonderful. The very first shot of the film was done once and in one take, and Wilder said, “It’s a print. Next.” I said, “What? Just the one take?” And I went to Mr. Wilder and said, “Can we do one more take? I think I can do better.” And he said, “Why didn’t you do it before?” We didn’t do it again. This was a very good lesson to me. You have to be ready for the first shot, and not the second, or third.

He was known to be very dictatorial about sticking to every letter of the script.

Absolutely. His scriptwriter, his co-writer, I.A.L. Diamond, was always there on set, with his pencil in hand, not looking at the actors and only following the script. I remember a scene in the studio: in the movie I was the concierge at this hotel in Greece, and I had to say to William Holden, as he was passing by me, “Mr. Detweiler, I have a message for you.” And we rehearsed. Then, when we did the scene with William Holden I said, “Oh, Mr. Detweiler, I have a message for you.” “Stop!” Wilder and Diamond stopped the shot. Diamond said, “Mario said, ‘Oh, Mr. Detweiler, I have a message for you.’ There is no ‘Oh.’” Wilder said, “Mario, did you say ‘Oh’?” I said, “I don’t know.” They asked the sound guy, and he said, “Yes, he did.” They said, “Why did you say ‘Oh,’ there is no ‘Oh’ in the script?” I said, “I don’t know.” They said, “Let’s do another one.” So we did it again and I said, “Oh,” again. And he we did it a second and third and a fourth time and every time I said, “Oh.” And every time they cut they scene. And finally Wilder was really desperate and he said, “Mario, I only want to understand, I really want to know why you always say ‘Oh, Mr. Detweiler.’ There is no ‘Oh.’” And then I screamed, “Because William Holden is too far away! Before he was just passing down here, in front of the desk, and now he’s coming down the stairs with 20 million extras, and I had to say ‘Oh’!” There was silence in the studio. Mario screams at Mr. Wilder, a scandal! Wilder walked up and down and thought about this, and went to Diamond and finally said, “The guy’s right. It’s ‘Oh.’ I’ll take this on my cap.” He said in German, “I take responsibility for that.” And he was the co-producer. He was always very funny and telling jokes; the wittiest man I ever met, besides Peter Ustinov. Sometimes I thought Paul Kohner and Wilder invited me to Los Angeles just to tell me jokes, so they’d have somebody to practice on.

Major Dundee

I’d like to go from a Billy Wilder set, which sounds like a very tight set, to a Peckinpah set, and Major Dundee which is legendary for being very loose and kind of crazy shooting experience.

Major Dundee was a very strange atmosphere. Peckinpah was crazy about Mexico. He loved Mexico, he loved the Mexicans, and he loved the Mexican’s history, which he considered a very bloody history, and he was fascinated by the suffering of the Mexican people. At the time he was married to a Mexican girl—well, I don’t know if they were really married. For instance we had a fiesta scene, which was supposed to take two days or so to film, but he did it over a week, every day again and again and again. And it was beautiful, and you could see it was full of life, a lot of alcohol and maybe drugs—I don’t know because nobody told me anything. But alcohol certainly. On the other hand there was no love between Charlton Heston and Richard Harris. Harris was always going [in Irish brogue] “Chuck Heston, you schoolteacher, you schoolteacher! You’re a schoolteacher” Because… for instance we shot where there were no trees, and we were all standing there with blankets on our heads to protect from the sun, and the assistant said, “Now come on gentlemen, mount your horses,” and Heston was the first on the horse. And he was [poses like a chest-puffed-out rider on an equestrian statue] on this big horse. They changed some scenes, they shot extra scenes for and with Richard Harris because he was not happy.

But for me it was a wonderful period. I loved Mexico, too. And I played a Mexican, and everybody said, “You look more Mexican than the Mexicans.” There was one day when one of the wranglers came to me and said, “Mario, you should come to Mexico and play my father.” I said, “Who is your father?” He said, “Pancho Villa. You should play Pancho Villa.” I said, “Pancho Villa, that’s a wonderful part.” Two years later I got a script from my agent and he called me, he said, “Mario, there is a film called Villa Rides Again.” And I said, “That’s a miracle, I always dreamed of playing Pancho Villa.” He said, “No, no, hold it man, it’s not Pancho Villa, it’s Lieutenant Fiero.” I said, “No, the only part for me is Pancho Villa. Who is playing Pancho Villa?” “Yul Brenner.” I said, “Yul Brenner is bald! I am Pancho Villa.” He said, “Mario, don’t be stupid, Lieutenant Fiero is a wonderful part. Will you think it over, I’ll call you in three days, you give me a decision if you want to play the part or not, otherwise I have to take another actor.” I didn’t call him, and then weeks later I heard he had taken Charles Bronson for the part. And Charles Bronson was the only one who was successful in this picture. It was not a successful film, but it restarted Bronson’s career.

When I had to go to contract with Peckinpah, with Columbia, for Major Dundee, I had to prove that I was able to ride, that I was good on horseback. So I was doing a picture in the Canary Islands where I played a Mexican, already. I had a cameraman take shots of me on my horse, I had a wonderful Spanish horse trained for bullfights. I enacted scenes where I showed that I could ride, that I was good on horseback, and these horses can always go without reins. You put the reins in your belt—as a bullfighter, you have to fight with free hands. So you put the reins here in your belt and the horse moves. This was wonderful, and it was convincing. But in my contract, it was written, if you’re not as good on horseback as you tell us, we can fire you.

Very first scene in Mexico, on the set of Major Dundee, in the morning I had to get myself a horse. And I came to the stable, and there was no horse anymore. They were all gone. And there were all these guys, sitting there and spitting tobacco. And I said, “Where is my horse?” And there was only one stall, with one horse. And then when I got closer, they said, “Can you saddle it?” I came to this stall, the horse was hammering on the wall: pow, pow, pow, pow, pow! I had to get inside, saddle him. And I asked the guy, “What’s his name?” And he said: “Satan.”

Okay. I got on Satan, and I had to bring a message, as Sergeant Gomez, to Charlton Heston, who was on a big horse, really enormous. It was the first shot of the film. And they had put the mark on the ground, and I had to stop here, for the camera, and give my message to the Major. I take Satan. Budda bum budda bum budda bum. No way. Ten feet away. “Mario, do it again, do it again.” Okay. Budda bum budda bum budda bum. I do it again, do it again. The other side. I never got Satan to stand on the mark. The assistant said, “Mario, just get off the horse and call Henry Wills.” Henry was the ramrod, the wrangler, the boss of all the 400 horses we had in the picture. Henry Wills, I knew already he was like a world champion. And Henry Wills came and got on Satan. And I said, “If he gets him to the mark, then I’m on the next plane back to Europe.” And he tried it. And Satan was already very nervous. And I was sitting there, very scared. But he did not make it. Two times he tried, twice. And then I said, “Ah, thank God.” And Henry said, “Change the horse.” And I got a second horse. I kept Satan for all the picture, but there were precise scenes where I had to stop or do certain things, I got another horse. This was my very first scene in Major Dundee.

It was not easy, because of the Nick Adams story. Shooting the scene in the fort where they had to mix all these Southern prisoners and so forth, they said, “Get yourself in the troop over there.” And all of them looked at me and stood there, and said, “Motherfucker, motherfucker, motherfucker, motherfucker.” Why? I hadn’t done anything to anybody. So, why did they say “Motherfucker?” Anyhow, I got to the front of the line. I said, “I’m the Sergeant, that’s my place, okay?” “Motherfucker, motherfucker, motherfucker.” Well, that’s a nice welcome!

So, later, they were all betting on the fight, Sonny Liston against Cassius Clay. And putting money on a rock. There was a big guy, a black guy, named Brock [Peters]. And then one said, “You see this big rock?” It was a big, black lava stone. And they bet money that Brock could lift the stone. He had wonderful muscles, big, big strong guy. He lifted the rock, and then he got the money. And I looked at the rock… and I come from a place in Germany, a particular place where there are these kind of lava rocks. I look at the rock and say: “I can make it. I can make it. As I know rocks, I can make it.” So I got my jacket off, and walk around there. And all the “Motherfucker” guys, they go, “Ha ha.” And I go there and I try. And I get it. I really got to lift it up like this. [Indicates a few inches from the ground]

The Italian Job

Just enough.

Just enough. Boom. And then Michael Anderson Jr. clapped his hands, I remember that, he clapped, gave me an applause, but not very kind. Then I went with Jim Hutton, who had done with me on the plane this scene giving me a “Heil Hitler”—he had grilled me if I was a Nazi or not. I found out that it was all for making fun. And then he went with me to this kind of taverna where Richard Harris was there playing the piano, and they were singing Irish songs. And Jim Hutton said, “We go in there,” and I said, “No, not with me.” But I went in there, and there was silence, like in a western. We got a table, and there was silence. And then Jim Hutton did the same scene he had done with me on the plane, “Have you been a Nazi?” And I said, “No, I never was a Nazi, I even was an anti-Nazi. I only fought zee Russians on zee Russian front, but never zee Americans on the western front.” Putting on a strong German accent, stronger than I had. And suddenly this big Brock got up and said, “I’m killing him, man.” And he got really dangerous, he really wanted to beat me up, you know. And Jim Hutton, he was a tall guy. He was really very, very, very big. He played in The Streets of San Francisco [TV, 1972-77] with Karl Malden, before Michael Douglas made the part. And then he got up and said, “Hold it, he’s making fun. He’s never been a Nazi…” and so forth. So this was the beginning of a friendship. And then they said, “Well, Mario, come on, let’s sing. What about Deutschland über alles?” I said, “Okay. Let’s sing Lili Marleen.” And then we slowly really made friends, you know. And then two days later after a scene the guys came and said, “Mario. Good reading. Great.”

At the end the studio bosses came, they said, “The picture has to finish on April 30.” We had four days shooting. And in the last two days Peckinpah never sat down, never got his boots off. With only the cameraman and two teams, he finished the picture. On the last day he looked like 20 years older. Really.

Around the same time, approximately, as you’re coming to Los Angeles, you start to work in Italy rather regularly. How did that came about?

The reason to go to Italy at the time was because Hollywood was actually taking place in Rome. So one day, [film director] Luigi Comencini called me. He spoke German, I did not speak Italian then. And he invited me come to Rome to do a part in his next picture. [A cavallo della tigre, 1961] You know the name of Gert Fröbe, who did Goldfinger? He played Goldfinger, the character, Goldfinger. Gert Fröbe was a famous, big guy, good actor, very funny. And when I went to meet Comencini, I knew Comencini by name, though Mario Monicelli was more famous. When I came to Rome, took for the first time the plane to Rome, I arrived and got off the plane and when Comencini saw me, he said, “Oh, Jesus, I confused you with Gert Fröbe!” And I said, “Oh, Mr. Comencini, I confused you with Mario Monicelli!” Monicelli was his friend, but Monicelli was more important. He laughed, and then we went to work.

I did the picture not speaking Italian, and phonetically learning my lines. The picture was wonderful, and the script was fantastic, by Age and Scarpelli, the best Italian screenwriters. It was a comedy, but also with serious edges, and it was not successful because Italians like pure comedy, and this was a little bit too serious. And Gian Maria Volontè, he was not known then in 1961. He played another part, we were four characters. It was a prison break movie. I played an Italian character, very strong guy, who always beat up the leading man, who was Nino Manfredi. He was not a villain, actually, he became the Manfredi character’s friend at the end of the film, and the other guy even treated him. It was not a real comedy, but a very good film. Today it is considered a masterpiece, Comencini’s best film.

And then over the next 10 years you go on to work in every genre that comes up in Italy: in spaghetti westerns and giallo and poliziotteschi. But when you first come to Italy in the ’60s, it’s the middle of this Commedia all’italiana cycle, and you work with some wonderful directors.

Yes, Dino Risi, I did with him Operazione San Gennaro [1966], with Nino Manfredi, Senta Berger, Harry Guardino, who played the American gangster. And it was a very, very successful film.

I particularly am very fond of the two parts that you play for Antonio Pietrangeli: Cucaracha in La visita [1963] and the banged-up, defeated boxer in I Knew Her Well [1965].

As A cavallo della tigre was not successful, I had a choice, either just go back to Germany or else stay on in Italy and accept small parts. And Pietrangeli, he offered me a part with the village idiot, Cucaracha, in La visita. It was a very small part, small scenes, it was actually seen as a character who lives in these village places, you know. Every village has this village idiot. I succeeded, and Pietrangeli liked me and it grew into quite a good part. I like very much the camerawork of Pietrangeli, Antonio was a very good director, very, very strong. Took many takes, not like Billy Wilder. In this picture, La visita, there is one scene that was 61 takes. Sixty-one.

He did wonderful scenes. He did one scene… I mean this is an absolute masterpiece. We did the picture on the River Po in Northern Italy. And there was a drawbridge, which could open and close again for the normal traffic of boats. And he had one scene in mind where it passes from afternoon, in a courtyard of a restaurant that overlooks this drawbridge. You could look out of the courtyard over this garden and this bridge, where sometimes a car passes. And what we did—we rehearsed for one day, and then we shot it the next day—was that at a certain time, you see the leading couple, François Perier and Sandra Milo, two protagonists, sitting at a table in the afternoon and drinking coffee. Then the camera goes to a big boat in the river, and it’s in the sunshine, the last of the setting sun going down. And the bridge opens and the boat passes. The boat passes into the dark, and it becomes night. And then it came back to the bridge. And across the bridge came 50 guys on these motorbikes, over the bridge. They passed by the restaurant, and then they come right into the garden, and there it was—everything changed, tables were set for dinner, and it was dark. And it was all in one shot. Armando Nannuzzi was the cameraman, one of the great cameramen of Italian pictures. I worked some times with him. But this for instance was Pierangeli. He was a real, real director. I liked him very much.

Lola

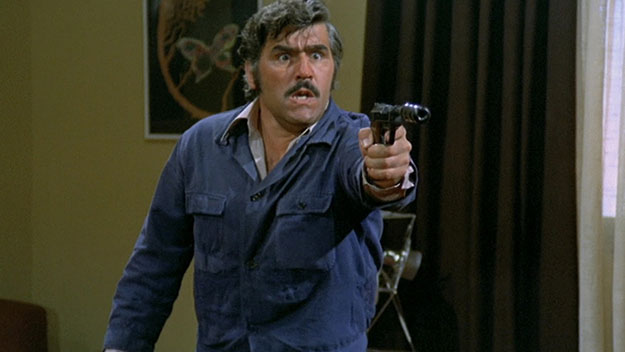

One specific set piece that I have to ask you about is the chase in Fernando Di Leo’s The Italian Connection [1972], where it’s pretty obvious that you’re doing your own stunt work.

First thing was, they tried to get a double, a stuntman, who looked like me. And all these guys were small, short, and very slim. Very sporty kind of men, very well trained, but nobody looked like me. And I said no problem, I’ll do this scene myself. And so Di Leo had me jump on this bus, this minibus, and do the entire scene. This was very, very, very hard. But I had for instance one idea. He wanted me to break the windshield with my head. Because before you saw this character do this to a telephone, break it with his head. He crushed with his forehead. Because he was angry, he BAM! crushed this telephone box with forehead. So he knew he had this very hard, thick skull. And he had the idea that I try to open the doors of the minibus, the doors won’t open. I broke three ribs doing this. Three ribs. Then I had to jump on the front, and they had put the two grips for me to hold on the front, which were not there, so I couldn’t hold on.

Then we went through the traffic of Milan. Not prepared streets with other cars from the production—it was the real traffic of Milan. And they went up to 50 miles per hour or so through this traffic. And I was hanging off the front of this minibus through all of it. And we’re trying to figure out: how can you break the windshield while the minibus is driving? And I had an idea. I said, “You get a technician with a hammer, and he’s inside. And when I do the movement, to break the windshield, take the hammer and break it from the inside.” Which worked beautifully. And everybody asked, “How could you do this?” This was a trick I invented. And then when we finally finished, when we fell off onto the street, I had to follow this guy on foot. It’s a long, long scene where I follow and run after him with my broken ribs, and I had a very hard time to run. This was very tough, was very tough. But I liked it, you know, I liked to do this work. And I was always very happy when I did not have to use a stunt man.

And then you come back and start working heavily in German films again, and you’re working with people like Volker Schlöndorff, with Fassbinder on Lola [1980], and even with Straub and Huillet on Class Relations [1984]. As someone who’d worked with Siodmak and Wilder and this generation of German filmmakers from before the war, you straddle these two very different worlds.

It took some time to get used to the difference. But then I said to myself, “These are the news guys, these are the future directors and so you have to work with them.” And after a short time I didn’t see any difference any more. I had no problem. For them it was a little bit the same thing. The first thing Schlöndorff said was, “Mario is too expensive.” But then when we met, we never had any problems. There were actors, other actors, they had a very hard time to work with these people, they’d say “They don’t know anything. What does he want to tell me, to teach me? He can’t teach me anything.” They had a different approach. I said, “No, that’s the future, you have to work with them,” and then it became rather easy.

Working with Straub and Huillet, for one example, must have been a pretty radically new experience.

Straub was an experience that was really outstanding, really unbelievable. He was really the purest cinematographer. To the letter. He was so strict. When the camera was standing there is was like it was built on a rock, you could not move. The strictest guy I’ve ever seen. It was not easy with Straub, because he and his wife, they were fanatics, lovers of cinema in its purest form, it was quite amazing. They lived very simply. They were really completely in the film and the story and how to make it. A year before shooting the film he came to me, to my place, to read the script. The third time he came to me he said, “You don’t know it by heart already?” I said, “We have almost a year!” He said, “You should know it by heart!” He said, “I have to ask you precise question. With this phrase, where do you want to breathe here?” I said, “I don’t know. I talk and then I breathe.” He said, “No, you have to decide, either you breathe before the end, or after the end, or here and there…” And he wrote this down. And then I made a joke, I said one long line in one breath. And he wrote out all of my dialogue on one line, nothing on the next line, he wrote it out all in one long line. So I took a deep breath and I rattled it out, “Blah blah blah.” And the next time he came with the script and my dialogue was these long lines, to the end, the margin. I thought it was a joke. But he was absolutely serious about this. And his wife was sitting on the floor and watching the prep of the actors, and she’d say, “He didn’t breathe or he did not this or did not that…”

All because you had the lungs for it. It looked like you took the stage at a pretty good run when you were collecting your award last night, too.

Well, the legs are still working!

Nick Pinkerton is a regular contributor to Film Comment and a member of the New York Film Critics Circle.