Interview: Malena Szlam

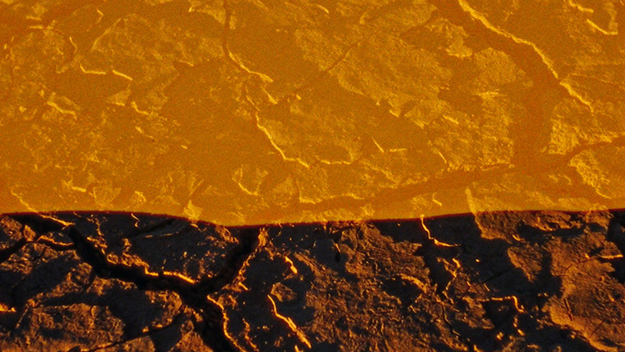

Images from ALTIPLANO (Malena Szlam, 2018)

A dance of horizons charged with the imperceptible vibrations of earth and sky: Malena Szlam’s ALTIPLANO (2018) ranks among the most striking landscape films of recent years and, indeed, calls for a revision of how we talk about landscape in cinema. The Montreal-based, Chilean-born Szlam films the reddish Andean Altiplano as if located on another planet (little surprise that NASA has used the region as a stand-in for the surface of Mars), an expanse of deserts, salt flats, remnants of volcanic activity, and lakes stained the same hue of their environs, that is as ancient as it is visually spellbinding. Rhythmically edited (largely in-camera), marked by a faintly delirious density of superimposition, and photographed (on 16mm, blown up to 35mm for exhibition) with the eye of a keen observer who wishes to dig deeper despite the impossibility of reaching beneath the surface of the dunes, mountains, and craters, ALTIPLANO ’s restlessly kinetic examination evokes the region’s political history as well as the present-day mineral exploitation underway there.

At first glimpse, ALTIPLANO resembles Szlam’s previous films, namely the moon portrait Lunar Almanac (2013). But it marks the first time that Szlam has incorporated sound in her work, deploying a pitch nearly inaudible to the human ear to conjure everything about the landscape that is beneath or beyond visual perception. The densely superimposed images suggest a landscape that is itself multiplicitous, one containing a diversity of natural features and having existed, in various iterations and across innumerable physical transformations, since the Pleistocene.

Indeed, ALTIPLANO feels as much like an act of scientific inquiry as it does an intricately choreographed attempt to draw out the landscape’s poetic force. Szlam’s rendering doesn’t so much arrest us by conveying the essential majesty of the landscape, but rather, the visual music and subliminal sound experimentation leave us curious about its material composition and the broader natural and political histories in which that composition has been determined. (For the past century or so, the region has been a hotbed for the mining of saltpeter, nitrate, and geothermic energy.) Following its many festival screenings (in the 2018 Toronto International Film Festival’s Wavelengths section, and at the 2019 Rotterdam International Film Festival and New Directors/New Films 2019, among others), an installed version of ALTIPLANO was presented at this year’s Jeonju International Film Festival. Szlam sat down with Film Comment to discuss geology and cinema, observation and approximation, the new role of sound in her work, and how time functions in ALTIPLANO (and cinema at large).

I wanted to begin with something you were discussing in your artist talk here in Jeonju yesterday; this notion of your films as being anti-observational and encompassing a more direct dialogue with landscapes and objects, a dialogue that’s nevertheless mediated by the camera. Could you elaborate on how you understand that dialogue, and how the camera mediates it?

I never thought of my films as being anti-observational, but I also don’t feel comfortable defining them as observations of landscapes themselves. This reduces the experience and the possibilities of what landscape, place, or region convey in terms of politics and the cultural, as well as the natural phenomena that occur in specific locations. I think it has to do with how I approach a specific place. In ALTIPLANO, I had of course done some research on the region, but because I know about it from growing up in Chile—and my mother’s family is from the northwest of Argentina—I thought of this as going to experience this area for the first time. So, there is research and planning, but at the same time, I don’t know what I’m going to encounter there. I traveled multiple times to film, and each time I sort of drafted a trajectory and tried to be open to other possibilities.

As for the camera mediating all of the experience, that has to do with making decisions on the spot, deciding what places I’m going to film, what techniques I’m going to use. I take notes while I’m filming, notes that I’m not necessarily going to go back to, but they accompany me throughout the process of filming, so that I can make the decision, for instance, to film sequences all through a 16mm roll in the evening at sunset, shooting until evening. Then, in the middle of the roll, I make the decision that for half of the roll something else is going to happen the day after. So I move to another location and I make decisions there in relation to what I remember I have already filmed.

When we think about landscape we generally have a topographical understanding of it—as something over there, something in the middle of a geographical layout. But yesterday, you were talking much more about geology than geography or topography. It occurred to me that there might be a relationship between sedimentation and the photochemical processes involved in your way of working. Do you think there’s some relationship there?

It was organic for me to use 16mm for this film. I’ve actually not done any other film similar to ALTIPLANO, so I was experimenting with different processes of workflow that I was not familiar with. I have been filming in the past 10 years with only Reversal Ektachrome, which is a film stock which was discontinued in 2013. In ALTIPLANO, I used some reversal stock and also started working with other film stocks, which meant that the process of creation changes. You have to think differently about the way you’re going to be filming—some of the footage I hand-processed, but while I was in Chile I was unable to hand-process negative stock and see the images immediately after filming. I had to go through a lab; I had to change the way I was working.

But going back to the connection with geology—it makes sense to see this analogy between the different layers of images that are printed, the motions that are printed on the film and these places that have large reserves of saltpeter, nitrate and different minerals. It has to do with these rocks and crystals and the shimmering of light on the surface of the Earth, or salt, and this idea of materials changing in time. And being corrosive. There is something about that in this landscape. And just the layers of the earth that you can observe in the mountains, the different minerals, the range of colors on a single rock there is enormous. And it makes me think in terms of the range of colors that also exist on film and which film can really capture.

In experimental cinema, landscapes are often viewed as ostensibly blank pages that nevertheless have some history inscribed within them—a hidden, concealed history that has to be revealed through the filmmaker’s intervention. But yesterday you seemed to argue for the impossibility of actually being able to read that history; how do you conceive of that impossibility?

“Approximation” is a word I will often refer to, because it relates to the work that scientists do. They try to understand the language of the Earth, whether it is expressed through the atmosphere, or in the cosmos, or in the ocean. They collect, observe, and analyze the data. Everything simplifies into an expression, whether that’s a sound frequency, or a color temperature, or a graphic that interprets or represents some phenomena. The phenomena itself, we just perceive it as an approximation. For instance, the film integrates infrasound recordings—seismic movements, volcanic activity and whale vocalizations. These recordings, as collected data, can be translated into another signal, into an audible sound frequency. Then what we hear has gone through a process in order for it to become audible or visible to humans. And that is why I was very interested in collaborating with [volcanologist] Clive Oppenheimer and [oceanographer] Susannah Buchan. As a filmmaker, I go to this region without knowing much, but observing and situating myself in these locations and gathering the place through the camera, capturing this phenomena that was happening, whether it was a sunset or anything that could be there. Landscapes hold so much history—millions of years—and we have fictionalized the idea of what that means.

But also there is this historical aspect. For instance, the Altiplano region is such a complex area in terms of the historical conflict in the past couple of centuries and what is going on right now. And we can be oblivious to this and just be on the surface of what the landscape expresses, or we can try to connect these different things in some way or another, without directly telling those stories.

If I’m not mistaken this is your first time making a work for cinema with sound?

Yes.

So then I’m curious, did your encounter with the landscape precede the decision to work with sound in ALTIPLANO or was it the other way around?

I’d been reflecting on sound as a medium. My experience with cinema has been very much about image-making, and not sound-making. So all my films before ALTIPLANO, including installations that had a relationship with the moving image, did not include sound, except if it was mechanical sound—handmade projectors. So eventually I wanted to challenge myself to work with both sound and the moving image. I had to try different things. The decision to work with sound was made before working on ALTIPLANO, and all throughout the making I was thinking “OK, what different approaches could I take?” I would try different things, and some of them didn’t work, and then eventually one thing led into another… I cannot imagine a better way to start working with sound than with sound that we cannot perceive but can only have an approximation of. That was fascinating, to go into that realm of invisible sound, impossible to hear and yet present.

And you said at some point you studied sculpture?

I studied visual arts at Universidad ARCIS in Chile, a very unique university for arts and social science that has existed for almost 40 years. After around 2002, the university was housed in a factory that used to be a metal foundry. The art school was divided into disciplines, but the artists, philosophers and sociologists teaching in the school approached art in a more interdisciplinary way, which was unusual then in a university context in Chile. I was mostly working with analog photography, printmaking and sculpture, and made installations that also used light and projections.

The connection between sculpture and installation is kind of obvious, but it also occurred to me that there might be some relationship between sculpture and editing in-camera.

Yes, editing in-camera requires a high degree of concentration and entails a degree of permanence in what you are doing, in the sense that there is some kind of meditative motion that happens, and that doesn’t happen all of the time. There are moments when it is just the right moment, and it flows. But it also has to do with memory, how to sculpt memory in some way, because I’m filming and I tend to not follow a structure, the structure takes shape while the film is being made. So, in some way, I can recall the experience of sculpting if I think in terms of the materials and decision making. This can go into any practice actually. But there is something about building images in the mind that I’m not able to see in an immediate way, and I have to recall the shape of those images, how they would be or become, if I’m filming this other surface or this other texture. It has to do with building and adding layers and creating an object that you never quite see or touch. A sculptural relationship happens.

In painting, if there’s something you don’t like, you can cover it up more or less; it’s a bit harder in sculpture.

Yes, exactly. You make a decision and then it’s done. I don’t work with a crew or an assistant, so I manage all the technical aspects myself. I’m at 4,000 meters above sea-level with a strong wind and holding a tripod. I’m getting the spot-meter, measuring light, I’m making my decisions, and I film. I know I have a 100 ASA film stock in the camera, but then I realize that somehow the spot-meter ring moved and it’s set for 50 ASA. [Laughs] These mistakes that I cannot erase lead me to make other decisions. So there is something kind of performative about the act of filming itself.

Can you talk a bit about the place of time in ALTIPLANO? It strikes me that in commonplace conceptions of landscape, we often talk in terms of space and history but not necessarily time per se. It also strikes me that an earlier work of yours was entitled Chronogram of Inexistent Time. Is time in ALTIPLANO an inexistent time?

Here we can draft so many answers. It’s fascinating how time has inspired humans to reflect in so many different ways.

Do you think of inexistent time as the composite time of cinema, of cutting, of juxtaposing images to create a duration that otherwise wouldn’t exist?

It can be taken from that perspective, but for me “inexistent time” means so many different things. We have invented so many devices and technologies to mediate time. But again, it goes back to this idea of approximation, and we still have a hard time explaining what time really is. So there is also this inability that we have to embrace. And it’s a beautiful inability. Knowing but not knowing, having but not having. We experience time, but it’s gone, or it’s happening. I think it also has to do with language and the relationship between time and language. That comes through with the idea of technology. Technologies become kinds of languages, in that they produce new ways of communication.

You’re fluent with the iPhone, or you’re not.

Yes. It’s this idea of permanence but impermanence at the same time. This notion of inexistent time, it exists but it doesn’t. Because time is a permanence. I feel like my work has been revolving around this point. In the case of Lunar Almanac it exists in some sense, where we simultaneously see a multiplicity of lunar faces dancing through the black screen, which is night. Or in the case of ALTIPLANO, I was so intrigued by how we could experience night and day together, that is, daylight and nightlight merged together. What kind of colors would reside there? It’s inexistent, but it becomes present through the medium of film, through the use of certain techniques.

This is present in Lunar Almanac as well: the evocation of time through the proliferation and repetition of superimposed images.

I mean, it’s cinematic, no? Cinema and time are sort of made for each other. Cinema and photography, the moving image and the still image, have this potential to create a temporal experience that can exist but doesn’t. We are inventing these kinds of fictionalized temporalities, but we are able to perceive them through cinema. It’s not just about having a camera and filming; it’s about creating the time within the image or the time within the collision of images. That sounded very abstract. [Laughs]

Dan Sullivan is a programmer at the Film Society of Lincoln Center and the co-editor of the Film section of the Brooklyn Rail.