Interview: Laida Lertxundi

Laida Lertxundi makes the most photographed city in the world seem strange, almost uncanny. Her shorts use the visual language of Hollywood cinema but drop out the narrative, leaving propulsively edited films that lend equal mystery to the Los Angeles skyline, rumpled sheets, or the curve of a neck. Born in Spain but based out of L.A., Lertxundi employs 16mm to conjure an atmosphere of languorous solitude and longing, backed by bursts of obscure soul music. On February 6, The Museum of Modern Art is holding An Evening with Laida Lertxundi that will screen a survey of her films, including the New York premiere of her latest, 025 Sunset Red (2016).

Film Comment spoke with Lertxundi by phone about what she learned from Thom Andersen, her music obsession, and her search for an embodied cinema.

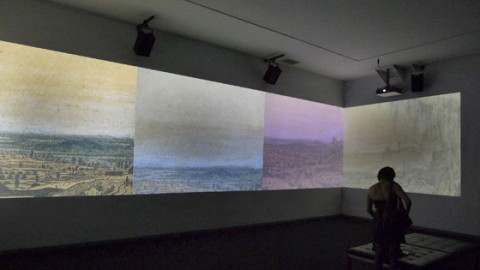

025 Sunset Red

I’ve been curious about your path from Spain to Los Angeles, and how you got into filmmaking.

I was really into music and photography and art in general growing up. Not really so much into film. I wasn’t drawn to narrative film, and I hadn’t seen any other kind growing up in the Basque Country. My brother was a cinephile, actually, and he watched all the Hitchcock movies and things like that. But there was nothing that really grabbed me.

Then I came to New York City. We had this intense political moment in the Basque Country with an armed group called ETA. My parents had a historian friend who wrote these books taking apart the myths of Basque nationalism. He was exiled and got a temporary job at NYU teaching history. So I went to visit him and got this idea, “Maybe I should study in New York,” and I ended up at Bard College.

When I arrived at Bard, my film history teacher John Pruitt showed Lemon by Hollis Frampton, Maya Deren films, Michael Snow (probably Wavelength). Just a few things over one night, and I was completely converted. I thought, “this is what I want to do”, because I was very interested in time. I had done photography, but I wanted to work with the medium of time. From there, my teacher at Bard, Peter Hutton, really insisted I go to CalArts, but I didn’t want to leave New York. Then I ended up here [Los Angeles]. It took me a long time to love it and then I really did…

Hutton’s films are really focused on landscape, as are yours in a different way. What was his influence on your work?

He was my first teacher, he taught me how to shoot. It was very hands-on, we would go up and down the Hudson River. We were taking history and theory classes separate from that. With him it was all practice. The idea was you would keep shooting and shooting until something accumulates. You didn’t need to have something completely planned. It’s also like an instrument, the camera, and you have to shoot a lot to learn how to get what you want. We shot landscapes. There’s something about his films, it’s really hard to describe them… The experience of the sublime. The ecstatic, transcendental quality of the way he captured things. I was definitely drawn to that as well. I didn’t really make landscape films when I was living in New York. It wasn’t the first thing I wanted to shoot, but everything comes around to landscape.

What were you shooting in New York?

There was a lot of shooting of the river in Peter’s classes. But it was cold, and coming from Spain, I shot of lot of indoors, kind of performance stuff. I actually had a background in dance growing up. I was interested in choreography. You see it in my films a little bit, the way I work with the body, but I did a lot of embarrassing performance things that I wouldn’t want to look at now.

Were you already working in 16mm or did that come later?

I started with 16mm right away. Peter Hutton didn’t do video at all. I learned video, I taught myself how to do it afterward.

Cry When It Happens

Then you went to Cal Arts for your master’s… What did you take from your teachers James Benning and Thom Andersen?

With James we had this amazing class called “Listening and Seeing.” We would meet really early in the morning on a Friday and not know where we were going. We’d get in a few cars and follow the car that he was in. Go to these pretty faraway landscapes all over California. You get to know the state pretty well with that class. He doesn’t talk very much. He doesn’t really lecture “this is how you should do this,” it’s more by way of example. You can see his working method by the way he taught that class. Finding these places and then having patience in them. We weren’t allowed to shoot or record anything, just take the place in. Rather than go out like a tourist and document something you haven’t had an experience with. That was really great. I observed a lot of process by working with him. I didn’t think about shooting, but about time and landscape.

Thom was my mentor. He writes about film and has more of that historian perspective. When I went to CalArts he had just released Los Angeles Plays Itself, and he lectured a lot from that. In the film he talks about how the industry here produces all these images that displace the city, block the reality of the city. That was really useful, the idea of treating Los Angeles outside the industry. Having to reclaim this space. I’m sort of obsessed with geography, and regions, because I come from a very specific region in the Basque country. Thom talks about things like “silly geography,” you know, where people in an action movie are driving down La Cienega Boulevard and then they make a left and they’re suddenly downtown. That was really grounding, to think about films’ relationship to a sense of place.

Since you were talking about how Thom approaches Los Angeles geography, I’d like to discuss yours. Your films make Los Angeles seem strange…

When you say strange, the first thing I think about is the diegetic situation. I am continuously interfering with that, going off-sync on purpose. You are looking at the space and wondering, “What is this space?” It is narrative-like, it mirrors the real time quality of our own life, not like a more abstracted experimental film. I don’t know how to explain it—I am interested in asking what constitutes space.

I’m interested in making films here in Los Angeles, thinking about the way I can play with the habits and expectations of narrative film language. That has everything to do with making films here. I don’t think this would have developed for me somewhere else. For instance, the idea of an eyeline match, you look where they are looking and see what they are seeing, I don’t know if you remember these cuts in Cry When It Happens [2010] between the sky and the motel—it’s like the crosscutting you’d have in an action film, going faster and faster, between these two static images.

The first film of yours I saw was Cry When It Happens, and I felt like it was pulling the city and myself inside-out, pleasurably disorienting. The other striking thing about that film is its use of music (the Blue Rondos’ “Little Baby” as an eruptive refrain), and I’d like to hear what music meant to you growing up, and how you use them in your work, as an emotional, sculptural element.

I’m just music-obsessed. I used to order these compilations from the U.K., from television, when I was a kid. I didn’t speak English then, but I was way into Otis Redding and all this soul music. I had a very personal relationship to it. It came from a time and place that I didn’t understand. As I got older, in high school I got into different music. In the Basque country there was this punk movement, a separatist movement, and the music was part of the activism, part of the culture. But when I went to Bard I got into small press things, I got into the romance of obscurity, the same way I’m interested in experimental films. This initiation, like something hidden that someone shows you and then you can share. I’m not a huge record collector, because I’m afraid of what might happen if I let myself. A lot of my friends are musicians or work at record stores or listen to music all the time, and are listening to things I might use for my films. People ask me about copyrights and stuff and whether I should worry about it. I wonder, I don’t know for sure, but maybe that’s why I use really obscure bands who often only have one hit. But that’s not the only reason.

A Lax Riddle Unit

Could you talk about the atmosphere you create on set? Your performers tend to be very languid, half asleep, like on A Lax Riddle Unit [2011].

With A Lax Riddle Unit I worked with my friend Josette. She really didn’t want to be filmed. I sort of like that. I’m interested in people that can be pretty deadpan on camera. Whatever is expressed is through their body. So her resistance was interesting to me. I work with people I know, and I work with people that I know are going to be subtle, that don’t really want to act. I have one friend who’s in all of my films (except the one in the arctic circle). She plays music in all of them and she’s very natural. She just shows up and we know what to do. Sometimes I do like to bring on people I’ve just met—it’s something specific what I’m looking for. I’m really into Robert Bresson, I love the way the bodies communicate in his films.

I guess I’m after something that is hard to describe. When I’m working with non-actors, how do you get them to be relaxed on camera? Not being too awake can help. So for Cry When it Happens we were meeting really early in the morning. Usually I know pretty quick. I do a test with someone. One time, for The Room Called Heaven [2012], there were these two guys picking up fruit from a bowl, in a medium close-up, and one hand was just acting too much. And I could tell without them speaking a word. I need people who can be on camera without acting, just doing these actions. That’s why I shoot so much that I don’t end up using. I wouldn’t recommend my working method to anyone, it’s really bad for my pocketbook.

There seems to be a shift in your couple of films, which try to capture interior landscapes more than exterior. In Vivir para Vivir/Live to Live [2015] you include your own echocardiogram.

It’s definitely a new way for me to think about relationships between sounds and images. It took me two years to make. I worked with Tashi Wada, who did the composition based on the cardiogram. And Ezra Buchla did the synthesizer wave based on an orgasm sound towards the end. He used to come in at the end for the sound mix, but these translations of sound to images took a lot of steps. There was more collaboration.

It was really fun for me, going to the doctor and getting a cardiogram made and thinking of it as a way of finding rhythm and structure for a film. When thinking about the body, and how to make an embodied work, this is a literal way. You see an EKG and hear a heartbeat, you can’t be more diegetic than that. Then Tashi used the cardiogram as a score, and made the composition you hear over the mountains, with the reed organ, later on in the film. I loved watching the image become sound. Though it’s my most abstract film and you don’t see many interactions between people, there’s so much body in it.

The part at the end, with the blue and red fields, are a recording of an orgasm, which was then put through a synthesizer wave—the blue is a shot of the sky in Death Valley and the red is what happens when you open the camera and the sun exposes the end of the roll. Christina Nguyen and I put these two colors in the optical printer and created an alternating pattern set to the sound.

I don’t know if I wanted to put myself in it, but that’s how it turned out. There’s something that’s become apparent in my work, a tension between the structure, the form, and the experiences. The tension between form and reality.

025 Sunset Red

I have not had the chance to see Sunset Red yet—its New York premiere is at MoMA. But before I see it, I’d like to know what your concept was going into it.

By the time I made Live to Live, my work kept getting read by some people as personal, like a kind of memoir. I thought, “This must be because I’m a woman.” The idea that I have no distance or conceptual approach to the work, when I spend so much time thinking about film construction, and working with people around me to be able to experiment with these ideas. After showing A Lax Riddle Unit at the New York Film Festival, somebody put their hand on my shoulder and said, “Don’t worry, it gets better. Until I turned 40 my love life was a disaster.” I didn’t know what he was talking about. This idea that a girl can only make a diary or something. It started to bother me.

Making 025 Sunset Red was like, fuck it, if you want a personal film I’ll make a personal film. It was going to premiere at Hammer Museum in L.A. and a musician friend asked “What is this film about?” and I said, “It’s like an abstract autobiography.” And they replied, “Isn’t that all your films?” and I said, “No! It’s just this one.” [Laughs]

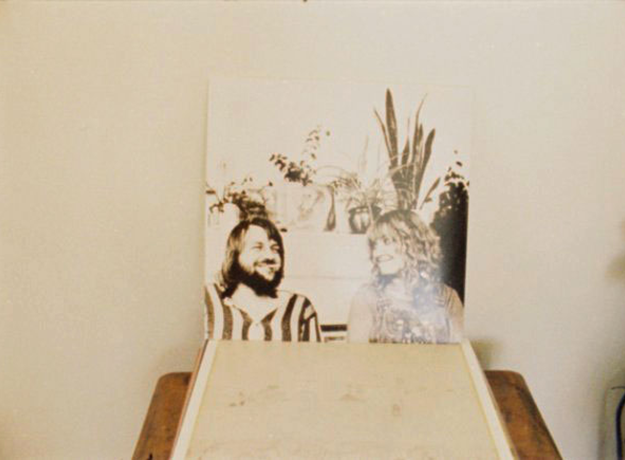

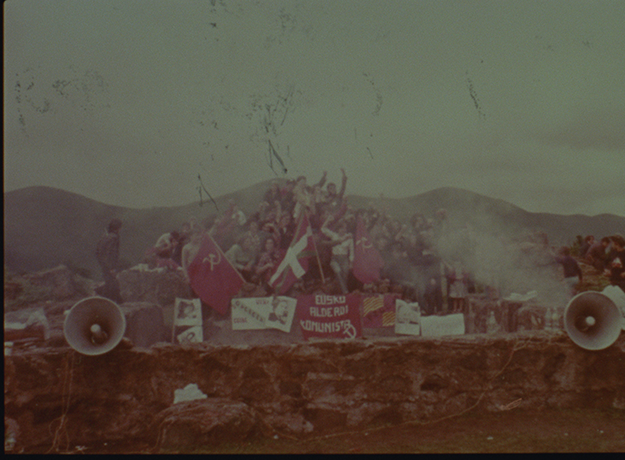

025 Sunset Red is the name of a filter that I use for a couple shots in the film. I got interested in talking about growing up with my family, who were political radicals during Franco’s Spain. My dad was head of the Communist party in the Basque region. It was a very specific upbringing. I just never talked about it much. And in college so many people were into Marxism and Communism and it was hard for me to think about it as something external. It took me a long time to think about how those ideas and values have shaped me. I used family photographs of that time, mostly of my father at Communist gatherings and such, and also my mom’s family, who were not in the Communist party but were radicals as well.

I struggled with making something so personal, and in the process something really opened up. I collected my own menstrual blood and used it to make paintings within the film. It also contains the first film I ever made. Before I learned cinematography, we had a found footage exercise with Peggy Ahwesh and I made a short structuralist film of a cowboy walking around a set, that’s in there too. I’m on camera kissing someone. It’s so much more… personal.

R. Emmet Sweeney writes a weekly column for Streamline, the official blog of FilmStruck. He also produces Blu-ray and DVD releases for Kino Lorber.