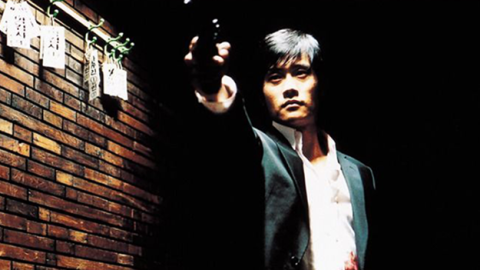

Interview: Kiyoshi Kurosawa

Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s French-language debut Daguerrotype stars Tahar Rahim as a photographer’s assistant in a contemporary Gothic tale about a widower (Olivier Gourmet) who uses archaic equipment to record his daughter (Constance Rousseau). Preceding Kurosawa’s recent Cannes premiere Before We Vanish, Daguerrotype (aka Le Secret de la chambre noire) dropped out of sight after premiering last year in the Toronto International Film Festival—where FILM COMMENT’s Violet Lucca chatted with Kurosawa and Rahim—but it resurfaces on July 18 for a screening in Japan Cuts at Japan Society.

Daguerrotype contains several themes that have arisen in your work before, specifically the idea that certain technologies carry spirits or have a kind of energy associated with them. Can you talk about the process of bringing this script to the screen and how you broke down the scenes?

Kiyoshi Kurosawa: In terms of bringing the script to the screen, the most challenging aspect was the actual daguerreotype equipment. There are certain parts that still exist, but what you see in the movie, the very large equipment, doesn’t exist anymore. So we had to re-create that and try to make it as authentic as possible. And once that was done, the other challenge was that nobody really knew how to operate it. We tried to do as good a job as possible, but we still were not totally sure or secure that “Wow, we’re really doing the right thing.”

It was the first time Alexis [Kavyrchine, the cinematographer] and I worked together, but we talked a lot beforehand. He watched my work, he knew my work, and I knew the work that he had done. So I was absolutely confident and trusted him completely to bring to the screen what I had in mind. We might have had a language barrier, sure, but I think that on the level of, “What movies do you like” and “What do you like in that movie,” we were completely on the same page.

Were there any films or works of art that you revisited before making this?

KK: Not really works of art per se. I asked Alexis to watch The Innocents to get into that mood.

Because there is a moment when the ghost of Denise menaces Stéphane, and the way she approaches and her face goes out of focus really reminded me of Inland Empire.

KK: This is the first time I’m hearing this insight. It reminds me of that movie as well.

The film plays up the tension between the photographic “truth” of what the daguerreotype is, and then the subjective truth of what’s going on in these two men’s minds. Can you discuss the aesthetic choices around this? It could’ve very easily been more melodramatic.

KK: This might be beside the point, but I want to touch upon the blurred distinction between reality and imagination. You could say that’s what’s actually taking place in the story, but filmmaking is very similar to that. We don’t really know what is fiction and what is reality. Obviously, I’m making movies, I’m not a still photographer or anything. It takes more than two hours of work to make one cut, trying to tell the actors: “Stand here. Wear this. And the costume should be this. And the object should be there.” So to make that one shot, we’re spending two hours. That’s completely crazy, right? But we believe that in that one cut, there will be some kind of spirit from us that goes into that, inhabiting that shot. If you didn’t believe that, you wouldn’t be doing this crazy thing that takes hours and hours. And in this day and age when digital technology is everywhere, anybody can shoot any kind of movie on their phones. It’s really an anachronistic thing that we’re doing. So this is where I’m coming from—again the distinction between being crazy and sane or reality and fiction.

You were saying it could have been more melodramatic, but from my point of view, I didn’t really intend it to be not melodramatic. But probably you are getting that sense because I’m Japanese, and from a Japanese standpoint, that’s all I could do. [Everybody laughs.] From a French point of view, the way that I describe the love between the young couple might be sort of unsatisfactory. But for me as a Japanese, that was way enough. [Everybody laughs.]

Tahar Rahim: I don’t really like it when it’s too melodramatic. When you think about it, my role in the film is that of an ordinary French guy who goes into a world and a family that are not ordinary at all. I think that I would have destabilized the film, if I had not been an ordinary young Frenchman who reacts in an absolutely normal way to all that is happening around him, though he is surprised by it all and says to himself “What the heck am I doing here?”

I don’t think that when you watch the film there are any scenes where I could have been more emotionally outward without risking being completely ridiculous. So really the point is not to break the interaction between the movie and the spectator, because all of his shots and the compositions are already so powerful and meticulously calculated that what the camera says is enough. If on top of that, we actors start doing a show, a performance, that would really completely break the balance.

Absolutely. The film is very restrained in a certain way, and I was curious how you got there. Was it through rehearsing, or did you start some place and then bring it down?

TR: Kiyoshi puts an enormous amount of trust into his actors and their understanding of the script and lets them bring what they want to bring to a character. I always have to talk a lot first with directors about the role before we start to shoot the film. Then I understand what they want, and I propose what I can bring to the table. As I said, everything you see on the screen is so meticulously calculated that the actor could actually just move physically in the frame and that would be enough to tell the story, just by what you see already in the background. From that point on, it’s a matter of understanding what I, as a French actor shooting a story in France, can bring to the table in terms of emotion and truth. And when we were overdoing it, he would tell us bring it down a notch, but he didn’t start out telling us to restrain ourselves.

What is most important or helpful to you as an actor in working and connecting with a filmmaker?

TR: To understand his universe and his world. That’s the most important. Because if you don’t understand that, it’s hard to portray someone and find the truth in any character.

Genre is such an important component of Kurosawa’s work. There’s the sense of a gentrification drama brewing with the high-rise buildings we see being built at the beginning, and the question of what’s going to happen to Stéphane’s land. How do you see that social issue interacting with the story surrounding the technology and the ghosts?

KK: Not being French and not knowing too much about social issues in France, I knew that I couldn’t really make a commentary on that at all. I know that it’s not really the movie’s job to just comment on social issues, but certain universal values transcend countries. So I knew that if I stuck to a few guidelines that are available in each genre, I could get my message through even though it’s to a non-Japanese audience. I think I managed to do that. What’s interesting is that when you actually start making the movie, you’re trying to stick to the genre guidelines and transcend borders and all that. But once you start filming on location, you can’t really block out what’s happening there at the time—it will make its way into the film. I tried to incorporate that.

It’s unavoidable.

KK: Trying to stick to a genre is important, but the fact that it was shot in Paris will be reflected inevitably. I think it’s very important to leave that in the film.

What is the funding situation in Japan at the moment? Do you see yourself making more films abroad? In the past you’ve said that you have to make a lot of films in order to stay alive in the Japanese market.

KK: The situation is, as you say, very difficult in Japan. It remains difficult. My pace is pretty much one movie a year. Foreign directors ask me, “How come you make so many movies?” and I say, “Well, if I’m not working, that means I’m unemployed.” So I’m out of work. So I can’t live. So I have to keep on making them. That is a very, very tough situation.

In Japan, usually what happens is the producer brings in a work and says, “Adapt this and then make a movie.” It’s very difficult to make a movie out of an original script. So that’s why I was able to do this in France. I couldn’t have done it in Japan.

Right now, we’re at a festival that has over 300 titles. We live in a time when it’s never been easier to see a film, but people also talk of feeling audience fatigue from having too many options. How do you deal with that as a director, and as an actor?

KK: I come from a generation for whom a movie should be seen in a theater, in a dark place with a large audience around you, getting all excited when it’s happening. I know that there are other ways of watching a movie, but I really can’t put myself in that perspective. What I think is that as long as they have movies and they’re showing them in theaters, it’s going to be okay. I want to be optimistic and not too gloomy about it. I know that people can watch movies on the Internet, but I’m hoping that those people are thinking about what it would be like to watch it in a theater. This is my sort of generational thinking.

TR: It’s true that it’s a growing problem, but I find Kiyoshi’s response really beautiful. I come from the theater and I like to go back to it. What you find in a theater [film or stage], you cannot find it anywhere else. It’s a state of semi-hypnosis, a sort of exchange with strangers without even speaking. We share a temporal space, an image, an emotion, without even needing to look each other in the eyes. We can’t experience this feeling unless we go to the theater. I’m convinced that there will always be people who will want to taste this experience. I believe that at one point people will actually get tired of watching things on a small screen, and they will return to movie theaters.