Interview: Katell Quillévéré

A surgeon, just before the incision is made, ducks underneath the blue sheets of an operating table and plugs headphones into the ears of a comatose boy, soothing him with music from his iPhone as his heart leaves his chest and enters another. The sense of anguish and affection palpable in the scene surfaces throughout Katell Quillévéré’s Heal the Living—the story of a young boy whose accidental death yields a donor heart for an ill older woman.

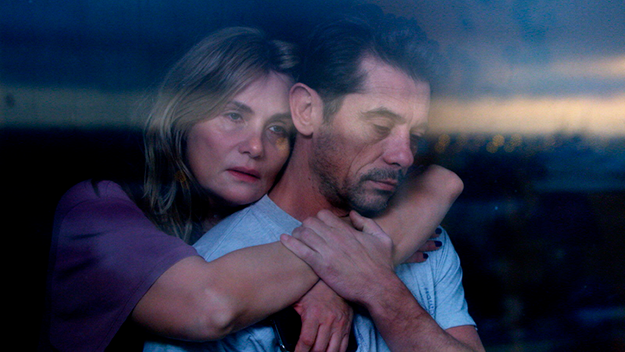

Quillévéré’s third film is a graceful ode to life amid distress and heartache, much like prior features Suzanne (2013) and Love Like Poison (2010), but it expands into new realms of lush visual expression. Adapted by Quillévéré from Maylis de Kerangal’s 2013 novel, Heal the Living beautifully literalizes the familiar axiom of human connection as a sprawling network of characters ripple across each other in countless waves, featuring a first-rate ensemble that includes Emmanuelle Seigner, Tahar Rahim, and Anne Dorval. Quillévéré explicitly portrays the mechanics of a life-saving operation, balancing this medical procedure with a generous account of a tragedy’s traumatic effects on the family. Like its visual motif of ocean waves, Heal the Living swells onto the screen. Quillévéré’s camera roams, tracks, and shifts among myriad characters and events, endowing the fragmentary pieces of her story with a rich introspection. It’s a searing medical melodrama and a fable of human interconnection that is aglow with clear-eyed compassion.

Quillévéré has never had a film released in the U.S. until now. Born in the Côte d’Ivoire and raised in Paris, Quillévéré studied cinema and philosophy at the University of Paris and soon afterward began directing short films. Love Like Poison, her debut feature, received the prestigious Prix Jean-Vigo, and Suzanne opened Critics’ Week at Cannes in 2013. Film Comment spoke with the director shortly before her film’s U.S. premiere in Rendezvous with French Cinema, in advance of its opening on April 14.

This is the first script of yours to be adapted from a different source. How much did you change from the novel when writing the script? What were some challenges?

It’s kind of a big process, so I think the main change from the novel is the fact that literature can easily deal with traveling through time, it can move from the past and the future, and this novel is really based on that principle. In a novel you have mental digressions from the characters between their memories and their present, but cinema is less comfortable with that, so I had to put that story much more into the present time. I really believe in the strength of cinema as being the art of the present. When you watch the first movies by the Lumières, you have this deep sense that this is really happening right now, and that is magical, and I really based my script on that faith.

I had to find a way to make every character exist in a singular way, but also at the present time, and this was the challenge for me. The biggest change from the novel is the second part of the film. The receiver of the heart transplant, Claire, doesn’t really exist in the novel, she’s more of a symbolic character who doesn’t have a life. The novel is more Simon’s story, the injured boy. I displaced the storyline of the novel to invent a life for that woman, inventing this relationship with her sons and really imagining who this woman is, so that the question of death is much more inside the movie, engendering life again. There’s more of a symmetry between the donor and the receiver.

Was it difficult to move from Suzanne, which concentrates on a few characters over the course of decades, to this film where about a dozen people respond to an event over the course of just a few days?

That was exciting, actually, an opposite challenge but the same questions in a sense of how to represent time in cinema, which is for me one of the most beautiful questions. To tell a story in 90 minutes is an amazing challenge and I love this idea, so Suzanne and Heal the Living are really just two ways to answer the same question.

In both of these films I’m amazed at the level of equanimity and empathy you allow for every character, no matter the circumstances. What, for you, is the connective tissue between your three feature films?

I think you’ve just said it in a beautiful way: they’re about the love for human beings. I’m really trying to make humanist movies. There’s a Jean Renoir phrase, “The drama in life is that everyone has their own reasons,” which is really important to me. This phrase is always in my mind when building stories and characters and it’s an important sentiment to me even in my own life, and I think it’s really the pinnacle of humanism.

I think another link between my films is the question of the fragility of existence. You can lose, from one day to another, a person you love, either because she doesn’t love you or dies or disappears. They’re about the difficulties of controlling life, and the push of life despite the dramatic aspect of unfortunate events. This resilient way of telling stories is really important for me. I’ve always been fascinated to see how brave people are in just living their lives.

The film lingers on individuals and grants us so many perspectives on each—the hospital nurse, Pierre’s girlfriend, the head of the hospital—and I found that while there are certainly key characters, the film is less about specific people than a network of them. How did you manage to balance all these different characters and viewpoints while still maintaining your own perspective on what’s happening?

The movie is precisely about this in-between, the line, like the line of the script, when death comes to life, and the part that each person plays in this trajectory that goes from life to death. For me to make this film both effective and human at the same time is to make it possible for all these characters to have a life outside of the characters they are playing on screen. It has to do with the structure of the film. They’re going along on this very straight path and then all of a sudden there’s a digression, a diversion, and a little playing of hooky, or doing something alone before going back to this major trajectory.

The surgeries in the film are quite striking but also strangely beautiful, something that is rarely shot so elegantly in film. What was it like to shoot the central transplant? How did you prepare for this?

Thank you. Yes, I did a lot of research. My camera operator and I sat in on heart transplants because, well, at first we were scared, but thought it was really important to go through this, to observe and to feel, to understand, and then represent this for the audience, and also observe what was happening not only on the scientific aspect but the artistic aspect. What is a heart? What does it look like? What’s inside of a body? How is a laboratory lit? And how can we transform that? It’s not just the question of being realistic, but representing the reality while saying something about the reality. That was a very moving job, and quite a lot of work. All the operation shots are effects, so it was a three-month process working with cinema professionals and with surgeons in order that everything would be done well.

This is your third feature film working with cinematographer Tom Harari, who also shot Suite Armoricaine and Le Lion est mort ce soir starring Jean-Pierre Léaud. Heal the Living has an amazing knack for color. I’m thinking specifically of that series of blue shots in the operating room. Could you talk a little about working with Tom, and how you both orchestrated this beautiful color palette in the film?

Tom is a friend of mine—we met when we were like 20 at university together. He’s made all my movies, all my shorts. So in our 15 years together we’ve talked a lot about movies, and we are really getting used to each other. We have the same culture and influences, it’s a familiar process by now. When we start a new movie together we talk about our main influences, usually the new things we saw in the time between making movies together, and we create a library with the important movies, pictures, paintings that are going to influence us. For this laboratory scene specifically we really thought of Caravaggio’s Saint Thomas, and the work of David Cronenberg.

That scene especially reminded me of Dead Ringers.

Definitely. I’ve been trying to figure out the English title, I’ve just went along all day calling it “the movie with the twins”! It’s one of my favorite films.

Talking about influences, while watching the film I was reminded of the Dardennes, Asghar Farhadi, and Hong Sang-soo. Which filmmakers especially influenced the film?

Yes, I was inspired by many filmmakers. In a way, the beginning of the movie is like a mutation, it’s a film that really dares to change its form depending on where it’s going. For the first part I was thinking of The Lords of Dogtown, a cult movie about skateboarding and surfing—you should see it, it’s excellent. The beginning is kind of a teenage movie, and I was inspired by that film, even if I chose to shoot mine in a much different way. There’s also the tradition of the American melodrama which really inspired me, directors like Douglas Sirk, James Brooks, even Kenneth Lonergan. Cronenberg was, of course, really important. I also was thinking about Steven Soderbergh’s The Knick for those shots of the operation.

There’s a moment where Claire and her sons are watching E.T. in bed, and the undertones of that film in yours is actually quite striking, where two people share one body, in a sense. Was this something you were thinking about deliberately?

Definitely. E.T. is about a transplant too.

The film’s score and musical cues are so essential to, as you said, creating a melodrama. Could you talk about the music, and working Alexandre Desplat?

I was surprised at first that he agreed to work with me. It was an enormous stroke of luck. I was convinced that the music would be important in creating that organic aspect. It’s kind of like a choral film, with about ten or so characters, and to fill this collective dimension the music was going to be essential. I wanted to find a melody, something that stays in your mind, and for me Desplat is a genius of the melody—he’s like a hit generator.

I was so impressed by how quickly he works. He is always dedicated to the director, even if they’re not famous, like me. What is important for him is what I want and what the movie needs, and he knows that I know what the movie needs, and he trusts me. It’s a question of principle, and that’s beautiful. With his experience he could much easier just listen to himself, but that’s not what he does, and I think it’s why he’s so talented.

Can you share some projects that you’re working on next?

I am co-writing a script for another French director, Hélier Cisterne. It’s his second feature film, a love story set during the Algerian war, and I think it’s going to be a beautiful movie. For myself, I’m taking my time right now. I also have a series about the birth of the hip hop movement in France about the group NTM. It’s not such a famous group in the U.S., but they’re a legend in France.

Both Heal the Living and Suzanne end somewhat optimistically, with characters coming to terms with themselves in spite of pain or distress. How do you reach this place of optimism or acceptance in your writing?

First and foremost, it’s a need for myself. You make movies to repair yourself from life. Your movie is always a mix of what you’ve been through, what you’re living, what you’re afraid to live and what you desire to live. In that way, for me the question of resilience and repairing and what you take back home from a movie into your own life is really important to me. I don’t think I would be able to have a desperate ending to any movie I make. I’m just not able to do that. It’s first for myself and then out of a responsibility to my movie and to the audience. It’s again the question of humanism.