Interview: Julien Temple

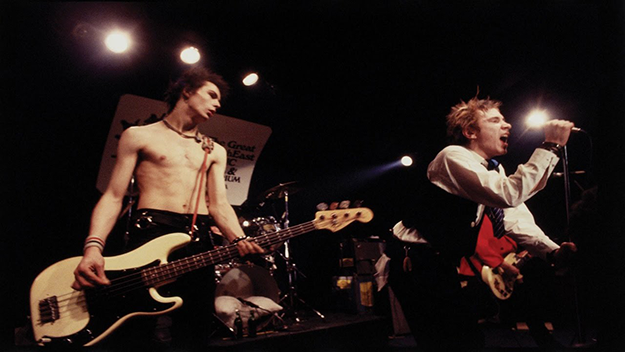

For all intents and purposes, Julien Temple was the chief film archivist of London’s punk scene in the late Seventies. While still a student at the National Film and Television School, Temple shot some of the earliest gigs by The Sex Pistols and The Clash at clubs like the Roxy. “I had a key cut to the camera room of the film school from which I could get a camera out at night,” he explained to me over the phone from his home in London. “It was cool as long as I got it back by about six in the morning. They wouldn’t know it had ever left the premises . . . I was the only one around with a camera.”

A part of the community from the start, Temple was witness and friend to these bands, immortalizing moments that got to the heart of the egalitarian values of the punk movement, such as The Sex Pistols’ 1977 Christmas Day benefit for striking firefighters in Huddersfield. (Temple eventually fashioned this footage into a documentary for the BBC called Never Mind the Baubles in 2013.) What distinguishes Temple’s approach from the vast majority of hagiographic, nostalgic documentaries on musicians is his ability to convey the ephemeral nature of performance while also addressing the larger cultural context in which they occurred, through found footage. “The Clash film [The Clash: New Year’s Day ’77] showed them before anyone else had filmed them, right at the beginning when they were coming together as a band, and that’s fascinating to see punk before it really hit in England, to see something being kind of built and explored as an idea.”

In conversation, Temple was loath to distill longtime friends and collaborators into anecdotes, but it was impossible not to ask him about a few of these seminal figures of punk. On Viv Albertine of The Slits: “I’ve really enjoyed her book. I think the best bit is about being kind of a Stepford wife in Hastings. Much more interesting than being a punk rocker.” Mick Jones, The Clash: “He’s a very wise man these days. He’s a great arranger and great thinker, musically, Mick. And I like his radicalism. He used to live in my flat but I can’t tell you what used to go on there.” On Joe Strummer, The Clash: “There was a sense of really getting beyond the star/fame thing in a very elegant way with him. There was no entourage, there was no kind of bubble, which is quite rare for people who communicate at that level and have that many people aware of them. So, to me, he was a fantastic at being a really great friend rather than a rock icon or whatever.” Ari Up, The Slits: “I heard a funny interview I did with her recently and I was trying very nervously to ask her these questions and all I got in response were these incredible screams actually.” John Lydon, The Sex Pistols: “I connected with him at a certain point of time when I thought he was incandescent. He was an inspiration.”

FILM COMMENT spoke with Temple about the era and about making music documentaries generally—including his latest, The Ecstasy of Wilko Johnson—on the eve of a retrospective of his music documentaries, shown in the Sound + Vision series at the Film Society of Lincoln Center.

The Clash: New Year’s Day ’77

So you were sneaking out with a camera at night and filming all these people. What was your intent? Was it just coming from a place of, “I’m compelled to document this” or “I just want to have a record of my friends”?

I felt compelled to do it. It was just so exciting, it was just like, stop everything else and do this and do it whatever way you could. And I was lucky enough to have copied a key to a locked door. I’d gone through the mid-Sixties London thing as a school kid with the Kinks and Stones, and that whole thing was incredibly exciting—to have songs written for you, as an audience, directly. ’64, ’65, ’66 was an incredible time in London. I was obviously too young to be involved in it, but in the punk time I was able to be a part of it, and filming was the way I found that I could do that.

Filmmaking seems very far removed from a punk aesthetic because it’s expensive and you need other people to assist. There have always been certain barriers that making music doesn’t necessarily have.

Well, it was very difficult filming punk at that time. Even rock ’n’ roll was very anti-film—asking someone like John Lydon or Keith Richards to do something twice at that point, they wouldn’t do it twice! They only did it once. But in film, if you weren’t running when they came through the door and you needed that to make the film, you had to ask them to do it again, which was quite a dangerous question to ask, certainly with the Pistols. But I think what helped was that I wasn’t a professional at all, I was a student, so I didn’t know really what I was doing and made mostly some big mistakes. But it probably turned out more interesting than if I had known how I was going to do it. I think a mostly professional outfit trying to film them wouldn’t have gotten very far.

The different archival material that you use—did that approach come out of the sense that, well, I didn’t get the shot of them doing X, Y, or Z, but I still want to express a certain something?

Yeah, I think that was a part of it. It was that, and then not having money. I mean, the original stuff I did with the Pistols was largely in the context of them being banned, so we made films when they couldn’t play. So we had footage of the band that we filmed, and then we would just shoot the TV for a night and then cut that up, which was a way of doing things very, very quickly. But it opened up a whole world of how to cut things together, things that you would never be able to write or conceive: you found these weird collisions of things that became really exciting. It was also hard to film them. It was either a kick in the lens or an incoming gob missile, which made for exciting shots, but for the narrative that you might need to tell, you would have to find other information avenues to use. It seemed to me that it didn’t matter where you got it from as long as you got it across. It was an important aesthetic, and it still in a way is what I feel. It doesn’t matter if it’s all on 35mm or on an [Arri] ALEXA, it’s great when it’s all on different formats and different ways of seeing reality. It’s all part of trying to tell your own personal truth.

The Filth and the Fury

Aside from the physical dangers—getting beaten up or risking damage to your camera—were there other difficulties?

I remember I filmed the Pistols in someplace where there was a condemned balcony in this old cinema that had a sign that said you mustn’t go up there—which is like an invitation to get this great top shot of the band. So I went up there during the gig, and sure enough, the balcony collapsed as I was filming and I fell onto the dance floor in front of them. All I remember is this incredible pain, but even worse than that was them just laughing and encouraging the crowd to laugh. So, yeah, no, fond memories.

Many of your music documentaries were made for the BBC, which has an incredible archive. When you’re initially preparing to start a project, what’s the procedure? Do you make specific requests?

I ask in the area of what I’m doing. I don’t like the idea of “give me a shot to illustrate this point.” It’s much more interesting to be hit by stuff you didn’t expect. I think the great aspect of that is that it makes the edit like the shoot: the same kind of chance, the same kind of random elements you have when you’re filming, you have in the cutting room because you’re working with stuff you haven’t seen before. It comes right out and knocks you over from the head and insists to be in the film in a way you can’t deny. That’s what’s really exciting about that kind of found footage. You just kind of know when it’s important to use it. That doesn’t always work, but your first instinct is usually pretty good. You can make use of something even though you thought it had nothing to do with what you were trying to tell a story about. And it means that the edit becomes as exciting as filming, and you want to be excited and engaged every moment of the process or you feel you’re betraying who you are in a way. It’s somehow boring. Which long periods in the cutting room can be. It’s a way of making it less boring.

When you are going through this process, do you ever earmark things or save them for later?

Yeah, I do. I’ve got whole drives full of stuff. We often pull old ones out to look at. The Pistols had given me a video recorder really early on to record them, but I recorded a lot of movies on TV. Then I decided that all these ads and weather programs and flotsam and jetsam of another time were so great—the best bits were the bits you didn’t mean to record at all. Trying to make sense of bits that don’t make sense is a good energy.

Dave Davies: Kinkdom Come

In instances where you weren’t necessarily there firsthand, when you’re making a film about, say, one of the Davies, what is the interaction for you personally between memory and this found footage?

It depends on the project. Part of me is a kind of a cultural historian, in a way. I’m really interested in the social dynamics of where this stuff came from. So there is a sort of historical, cultural element to these films. It’s different in the new Wilko film, The Ecstasy of Wilko Johnson, where I just would lie half awake and half asleep and just let these images of films that I saw when I was a kid that somehow connected with the idea of mortality in whatever way, just let them float into my headspace—I think you need a high ceiling for this, but it seemed to work. These things would just sort of float in and connect to things that he said in very random ways. So that was different than sitting in front of material and fast-forwarding through loads of archives. It was trying to conjure up or receive images from my memory of films that connected to the subject, which was a really interesting way of working for me. It seemed to suit the kind of dream state that Wilko was in during this year when he thought he was going to die.

I just filmed him secretly watching the new film. Because he has a thing of not wanting to see the film until everyone else sees it, which seems a bit masochistic. So he hadn’t seen this film when we had the premiere. So I snuck a night-vision camera in and wedged it between the seats in front of him and filmed him watching the film, which is quite an amazing ride because the film is such a dramatic thing: thinking he’s dead for a year and then being told he might live. To see that playing out on his face as he watches the film is quite bizarre, actually. We’re calling it Watch with Wilko. There was a very famous radio thing called Listen with Mother, which all the Sixties British rockers grew up on, in the early Fifties. It was a program for kids like Keith Moon and Keith Richards. So this is Watch with Wilko. He’s a happening guy, Wilko. He’s got a lot going on in that skull. I think he’s kind of half-dolphin—there’s a bit of dolphin in him if you look at the shape of his skull.

Do you ever show your other subjects the film as you’re making it, or let them guide what the footage you’re putting in is?

I think it’s better not to be controlled by the subject of the film. Films made in that way seem completely bland and uninteresting. So it’s better that you have the rapport with someone. I’m not going to make a film just to put someone down—I wouldn’t do that. Basically I’m celebrating people, but as people, as human beings, rather than as distant rock stars. It’s much more important, that connection with the world they came from, with the audience, with their time, to me, than picking them up for a record company. And that kind of control gets scary: you can’t tell the truth, you can’t tell your own truth, if you’re messing with that. I think there’s a big problem with putting images to music: that you can shut it down. You try to provoke with the combination of music and images, provoke a kind of opening up rather than closing down. A lot of films that are made about music kill it, really—they put it in some sort of visual box, but it doesn’t deserve to be. It’s much more powerful than that. But I think the right kind of imagery, like the right movement if someone’s dancing to music, can make it bigger than it is. Or give you other ways of appreciating it that don’t injure it.

The Ecstasy of Wilko Johnson

Yeah, a friend of mine likes to dismiss a bad documentary by saying “That could have been a podcast,” because it’s just some talking head speaking, and then you see them doing what they’re doing as they’re speaking over it. It’s this very cut-and-dry thing that has no visual sense. It’s the worst feeling in the world to see a biopic or a documentary about your favorite band where afterward you think: “I could have just spent two hours listening to their music instead of going through this tedious thing.” In the past when you were working with music videos, did you ever feel more restrained by what the label wanted, rather than, as you said, an opening up?

Yeah, definitely. The good thing about working in that medium early on was that the record companies didn’t really understand what was going on so you could make very personal films in a way that became much more difficult later when they kind of sensed it was kind of an advertising medium and you’re selling teddy bears to people or whatever. I still think the few best videos are fantastic things, but they’re the ones that seem to escape the controlling mechanism that’s become more and more desperate as record companies sell less and less records. There was a freedom in the beginning that made it exciting, a sense that you could get an image that came out of your head on video and two weeks later it would be in Tokyo and Rio and L.A. and be around the world, which was incredible. That was the first time that was possible.

Do you mourn that loss? Or now that the music industry is—

I don’t want to go back to that period at all. It was exciting when it happened. I prefer a documentary where the filmmaker is free to say what they feel about the people who made the music and the time it came from, whether it’s now or then or never. I think it’s an important area of filmmaking at the moment because it is relatively free: with music, you don’t have a scripted, narrative feeling. It’s a different kinetic with images and music, and there are no other types of filmmaking which can be very explosive and very enervating and can still pack an emotional narrative journey. Hopefully.