Interview: Jodie Mack

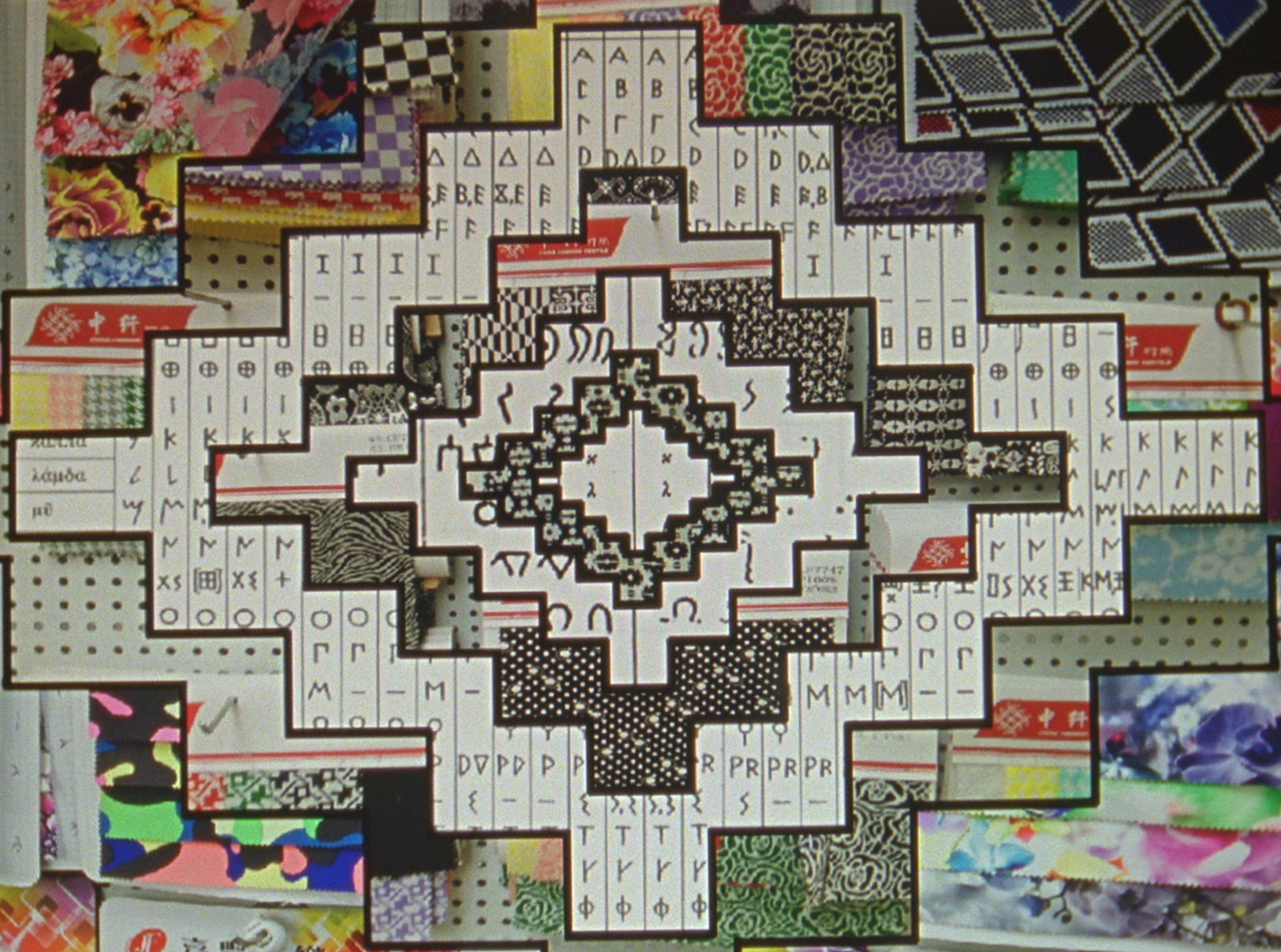

Following nearly a decade of film, video, and gallery work, American animator Jodie Mack experienced something of a breakthrough in 2013 with “Let Your Light Shine,” a traveling program of five short and medium-length 16mm films that traversed everything from classic stop-motion animation to 3-D light spectacle. That same year, she quietly began work on her first feature; the resulting 60-minute film, The Grand Bizarre, is the culmination of Mack’s many varied interests and experiments to date. Shot in a dozen countries, the film finds Mack’s trademark, color-coordinated textiles dancing across a variety of exotic locales (India, Mexico, Holland, Morocco, and Turkey represent just a partial itinerary) through a meticulous process of frame-by-frame photography and practical production magic. Playful and propulsive, Mack’s animations conjure an array of visual patterns, which in turn generate a multitude of motifs that together speak in potent shorthand to the economic and industrial development of fabric manufacturing the world over. In Mack’s dazzling montage, everyday sources—maps, globes, plane tickets, even back tattoos—reveal both cross-cultural codes and universal truths, bringing this eclectic cinematic travelogue into seamless dialogue with each viewer’s unique worldview. Driven by a homemade soundtrack that locates a heretofore unrealized intersection between hip-hop, chiptune, and synth-pop, The Grand Bizarre tackles lofty themes at an intimate scale, imbuing familiar forms with a subtle but incisive sociopolitical force.

In the weeks following The Grand Bizarre’s premiere at the 71st Locarno Festival, Mack corresponded with me about the film’s lengthy production, its simultaneously rhythmic and modular construction, the challenge of interrogating pop music through unconventional means, and the gratifyingly surreal feeling when your work is commissioned for a Times Square visual art exhibit. The Grand Bizarre screens September 8 and 10 at the Toronto International Film Festival, before heading to the New York Film Festival in October.

You’ve been working on The Grand Bizarre for over five years. Was it always conceived as a feature, or did the scope expand from ideas and/or materials you were already gathering that you thought might work best as part of a larger project?

I did not originally conceive of the film as a feature or as anything really. It started by taking snippets here and there, building minor collections and assessing under the camera over time. But, yes, I suppose that as soon as I saw a glimmer of its potential, I did envision a feature. I actually envisioned something much longer than the film’s final running time. At one point, I considered using the songs that move the film as modules that one could rearrange and play in any order as well. But, ultimately, I decided it was a challenge to find a way to move through all of these spaces and ideas within a one-hour timeframe and that the unit of an hour was very important to the grouping of themes I was exploring, regarding the standardization of space and time, grid structure, industrialized living, etc.

Where did the travelogue aspect of the film originate? Were these snippets and minor collections you were gathering a separate consideration from the settings, or were the materials bound up with the locations?

The idea of the travelogue came from the inescapable fact that some of the areas I was shooting were obviously very different places. But I decided to try and permeate the genre of the travelogue specifically because I was thinking a lot about the simultaneous development of the cinema and travel industries; early travel plays and their relationship to conventional or fantastical storytelling methods; and the development of cinema as a teaching tool within the education industry. The collections I’m referring to are at once material, spatial, and temporal: objects, places, and animations/records. The specific lens of my film aimed for observing a place through objects, and, in theory, the whole movie could have occurred within animation stand space [the studio-based world where Mack’s films traditionally take shape], or the Internet. But I had technical and life goals to make movies outside in the world.

Whether or not the materials were bound up with the locations was an early and central question to this project. Each object carried with it a different history that developed among the history of trade, shifting technology, hybrids of indigenous and colonial contributions, and the orientalist/ornamentalist ping-ponging of designs—patterns, rhythms, slang. The motifs of the patterns in the textiles—or music, or language, or food—function not only as signifiers of culture but also as signifiers of cultural dilution. So I was wondering how the role of graphic motifs in commerce contributes to our understanding of the forms and how/if this “journey” could locate visual and sonic inventories of globalized identity, a global vernacular of patterns. So, instead of functioning as a travelogue that studies place, I think it actually intends to imply a sense of simultaneity as it pieces together the visual and sonic components of intricate systems of communication and trade through an investigation of simple objects. As it sifts its way through kimchi-taco hybridity in culture, the film prompts interrogations of past/authentic/artisanal production as it attempts to connect the dots surrounding the complexities of contemporary citizenship.

This is all to say that, for a moment, I experimented with a sort of day-for-night, x-place-for-z place, toying with interrupting these sort of Barthes [Simpson]-esque ideas, like “you need to have the red-and-white checkered tablecloth to imply the Italian pizza restaurant” sorts of photographic codes. I started bringing fabrics from elsewhere to shoot in other locations, whether the relationship was clear or not. The plant life or architecture or a place each brought a new set of codes with which I could work with or against in the varying animation sequences. Then, at a certain point, I became interested in points of origin and departure—fabric in site of its own making, fabric in transit, fabric reflected in mirrors. With each “snippet” I eventually developed my own schemas of codes that I could use to employ my own cinematic language.

As far as taking your practice outside of animation stand space, can you explain what the technical process entailed with regards to animating the spaces/places seen in the film? I imagine you’re working with dozens of materials for any given sequence, and then photographing individual fabrics in a variety of setups, all of which must add up to a fairly laborious process. Are these sequences mapped out beforehand in any kind of visual way, even if just for your own reference?

Each individual shoot had a different set of rules, different planning possibilities. Most of the first shots I captured were, for the most part, in peoples’ backyards, on rooftops––in isolated spaces. I was not picky and did not try to pre-scout locations. I had nothing, so I only had what I had. If someone offered me his/her space, a brick wall was good enough for me! Whether there was a wall, a table, a window, I would make it work. I sought out the interesting light within the spaces, which brought about many of the light-dance sequences. As the project moved along, I accumulated different sorts of shot groupings: stairs, mirrors, landscapes, interiors, factories, stores, etc. So I started looking for those things to build those groups. But ultimately, the locations themselves were often based on convenience: the workability of the space, the feasibility of running back and forth between the objects and camera to take the frames.

I used varying amounts of fabrics for the animation sequences––sometimes much more than a dozen, sometimes less. There is this sort of strange dance performance that occurs as the animation shoot goes on by placing the “used” fabrics into different piles that are then recombined over and over to keep the order random. The size/weight/texture of the textiles governed many of the animation possibilities for varying scenes, and those were assessed alongside the spatial possibilities of the locations. The process involved bringing the fabrics, tripod, light meter, gaff tape, etc., to a given place; setting up the camera and tripod; devising a way to hold the fabrics upright: my famous tape loops, safety pins, clips, etc.; and then shooting. I filmed all of the exterior shots without stopping and as fast as possible to align with the moving sun or other elements in the background. Each shot took probably between one to four hours to complete and entailed me running back and forth between the fabrics and camera or the on-screen fabrics and an off-screen pile while someone else captured the frames on the camera. Wind was often an issue, and fabrics fell down a lot. Some of this made it into the film.

I designed the timing of the shots around rhythmic modules. I shot at compatible timing frequencies with a range of time signatures and BPMs—11/8 in 108 BPM; 4/4 in 120 BPM etc.—and generally “overshot”, shooting at least 32 bars of material and sometimes much more. In the cases where I shot moving light, for example, I would just have to keep shooting until the light exited the frame. Sometimes this resulted in carefully winding the camera motor after it ran out so as not to move the camera or disturb the scene. But, generally, to answer your question, each setup required a new set of tools. Pre-planning felt impossible and virtually out-of-sync with my interest in the possibilities of truth in documentary. So, in most cases, I worked within the constraints of what was available to me and adapted to each scenario with a new set of strategies.

How did you go about constructing the soundtrack in relation to these rhythmic modules on which the shots were designed? Were you timing out these sequences with certain kinds of music in mind while you were shooting? And at what point did you realize you’d be recording the music yourself?

I knew that I wanted to interrogate “normal” pop-music timing (often 4/4), but I also knew I wanted to construct sequences with some far-out time signatures. I also approximated some of the patterns on the textiles with the sounds. For instance, the strange scales at the end of the first song are the result of arranging a pitched digital instrument into the shape of the diamond motif—the information vortex—that occurs many times throughout the film. So I would shoot according to certain predetermined patterns with some sonic ideas in mind and then shoot according to a “time script” not too dissimilar from Merrie Melodies–esque musical dope sheet industry-animation style.

I did not know that I wanted to approach this film musically at the start. But once I did, I knew that pop music was the genre I was going to investigate because it speaks to the homogenization of pattern for greater productivity. It represents the simplifying of sounds and musical structures that occurs as technology upgrades. To me, this plays out in the history of musical notation: classic Western notation morphing into tablature or even just letters of the chords in popular song books that people without learned, acquired skill could access and approach. I’m excited about pop music because it really prods at the divide between high and low culture within which I find infinite inspiration. And it’s everywhere, a place that folks can find a common ground.

I knew I wanted to do the music myself. The ambition of the project was out of my league, but I wanted to try. There was a potential direction including lots of popular songs, including “Fantastic Voyage” [Lakeside, Coolio] and “America” from West Side Story. But, finally, I decided and stuck to the idea of fake and quirky global Muzak genericism.

How about some of the more playful musical moments, such as when you interpolate the Skype ringtone or build beats around found sounds: were these spontaneous inspirations? Did you find yourself registering the patterns in everyday life more and more as you began to develop the film’s many correspondences?

I totally forgot about Skype for a second! That was my exception, plus the two different parts of the two different versions of “Rhythm of the Night” [DeBarge and Corona] that play from what’s assumed as moving cars. Although I wanted to do things myself, I couldn’t resist a few tips of the hat to pre-existing elements of the global sonic vernacular because the film was supposed to be about the gradual slippage of meaning that occurs through the economy, technological exchange, etc. And I have a bad habit of venturing into Internet rabbit holes with techno covers of things. Techno Phantom of the Opera? Sesame Street? Tori Amos? No problem, the Internet has you covered. There was, at one point, a thread involving cell phones while traveling––strange pronunciations in Google Maps; asking for the WiFi code; getting WhatsApp messages from traveling buddies months/years after meeting them… at 3a.m…. time differences! And, again, considering the cinema as this portal of travel and understanding the Internet as a more immediate and user-interfacing continuation of that travel portal that transcends physical space—and therefore time and therefore the construction of one’s experience. Lo and behold, the Internet contains dozens of Skype remixes! So, I used one of them alongside my friend Chris Hontos’s remix of one of my songs for that part. Instead of using the cell-phone theme as a recurring motif in the film, mirrors functioned as a placeholder in one section/row of the textile.

I knew that I wanted to incorporate “diegetic” sounds for the spaces into the actual musical constructions. I wanted to use these sounds and impose on them the structures of “music” as a way to approach ideas surrounding the ways that humans devise systems of measurement and quantification to describe the ineffable: time, perspective, musical pitch, latitude and longitude, etc. I took a lot of care to record and assemble different sample banks: rural exterior sounds; urban exterior sounds; machine sounds; phonemes. I worked from the International Phonetic Alphabet to construct a fairly comprehensive sample bank of its categories and sub-groupings: pulmonic and non-pulmonic consonants; diacritics, etc. And once I had a good amount of material to work with, I began to construct the music and thought carefully about working with the groups as separate and complementary elements and how they could build over time.

And, yes, the visual and sonic patterns appear everywhere to me now. Sometimes I’ll just walk through the airport and see a diamond suitcase while listening to a techno remix of, I dunno, Jewel or something. And I’ll blurt out: “THE GRAND BIZARRE!”

Can you tell me how you went about structuring the film? You mentioned that the 60-minute runtime isn’t a coincidence. Knowing the overall shape you wanted, how was it actually experimenting with the edit? The film feels very precisely paced, with concentrated bursts of activity chased by calmer passages, both visually and sonically.

The length is and isn’t a coincidence. Once I knew it would be long-form, the question was: how long? I sorted through comments from grant panels suggesting the piece should actually be shorter than intended and worked through ideas involving the piece being much longer than it is now—possibly three hours or even looping infinitely. I knew I wanted to make the piece on 16mm, and 60 minutes is the max I could fit on one reel of 16mm film. But that was a eureka moment for the length of the piece because one hour fits on one reel, because one hour is the unit of time we’ve decided upon as humans, and because one hour would be the perfect amount of time to use the clock as a stand in for a globe and to circle around together!

The edit was a seemingly endless black hole of confusion and doubt alongside a sense of possibility and hope. I teetered between visualizing it as a tunnel or a road with interesting sites and experiences along the way. There were so many options, so many routes and strategies to consider. Plus, I wouldn’t stop shooting! I have notebook drafts of entirely different films from the same material. I feared that I was biting off way more than I could chew and allowed option paralysis to intervene for a while. But I needed to go through that process to settle upon the film documenting a journey into an unknown, using real materials and spaces but essentially traveling off into the cosmos with its positing of the components of intricate systems of communication, bodies of knowledge, technology, trade, high and low culture, etc. There is something about the impossibility of grasping all of that at once––that problem became the inspiration for my film and the main feeling I wished to convey.

Then it became really fun. I found so much power in editing and found tremendous pleasure forcing the film to move along. The film is roughly structured as a textile with fringes at the beginning and end—fire sequence; end sequence. Each “song” is a new set of lines moving down the textile and contains a different motif. The ebullient vs. relaxed movements you mentioned: those are the motifs and the decorative lines between lines.

The film ended up feeling a lot more open than some of the original plans. I decided that keeping it this way would allow for the multiplicity of meanings you could pull from a film about the multiplicities of meanings. I am proud of the film’s commitment to exploration and of the way it accumulates ideas over time. I learned a tremendous amount about editing and sound during this process and see it playing into my work in the future.

I’m curious about the mirror motif you mentioned earlier: first, where the idea came from to utilize these various reflective surfaces in this way and how they fit into the overall thematic scope of the film, and second, how the shots were actually achieved. On first viewing I think I wrongly assumed that you shot the mirrors in a traditional fashion and then added the animations after the fact. But when I looked at the film again it seems like you actually placed the various textiles off camera and then shot the reflections in the mirrors frame by frame. Is that right?

Ah, yes, the mirrors; they’re some of my favorite shots. I actually started shooting in car mirrors after I met a driver I really liked. I just actually liked driving around in his car all day and hanging out with him. The windows of his car really encased my experience. I didn’t want to leave the car! So shooting in the mirror made sense. And the footage was, like, wow, so I kept on with the mirrors and expanded to things like windows and other frames within frames. As I mentioned before, there was an impulse to use the mirrors as substitutes for the cell phone in many cases.

But the mirrors were infinitely rich to me. They summed up a lot about a Western conception of self; indivi[dualism]; the understanding of self as laborer; selfies, self-marketing; the human impulse for mimicry; reflexive mimesis; imaginary—symbolic and real—order, feedback chambers of ideas and the gray areas of knowledge and understanding bouncing back and forth between journey and reflection.

And, yes, I shot the mirror scenes in-camera by angling them to reflect the fabrics and holding new fabrics in the right position to get the reflection while in the animation. This was, in some cases, a two-person job.

Before we finish up can you tell me a little about the upcoming =project where your animations will be projected in Time Square?

In September, a reworking of my film Posthaste Perennial Pattern will show on a few dozen screens in Times Square every night from 11:57p.m. to midnight. The opportunity is through the Times Square Art Alliance and their series “Midnight Moment,” which features rotating monthly artists. My particular contribution is in conjunction with Museum of Arts and Design and the closing of the exhibition “Surface/Depth: The Decorative After Miriam Schapiro,” curated by Elissa Auther. The show includes 29 works by Schapiro alongside 28 works by contemporary artists expanding notions of the decorative including Sanford Biggers, Josh Blackwell, Edie Fake, Jeffrey Gibson, Judy Ledgerwood, Sara Rahbar, Ruth Root, Jasmin Sian, and myself. I am showing nine works from my ongoing “No Kill Shelter” series. I chose to include Posthaste Perennial Pattern in “Midnight Moment” for its correlation with Schapiro’s The Beauty of Summer [1973-74]. I am really excited to bring my work to this new forum designed for advertising. And I’m especially thrilled to be doing so with MAD. Working with the museum for this show has been such a positive experience. In addition to the show and this, we also did two film programs: a program of my fabric-flickers and another program of films related to pattern, including Shirley Clarke, Harry Smith, Kenneth Anger, Yongbaek Lee, etc. Knowing how shafted experimental film has been historically within definitions and markets of/for art, it’s exhilarating to have stuff shown in a museum focusing on the tension between art vs. craft and to now bring these concerns to the Jumbotron, to the street! It should be fun to watch the wires cross.

Jordan Cronk is a critic and programmer based in Los Angeles. He runs Acropolis Cinema, a screening series for experimental and undistributed films, and is co-director of the Locarno in Los Angeles film festival.