Interview: Joanna Hogg

For more from this interview, and on The Souvenir, go to the May-June 2019 issue of Film Comment.

The Souvenir (Joanna Hogg, 2019)

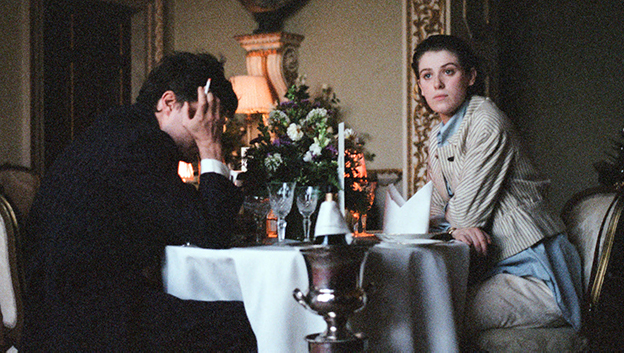

A clear standout at Sundance 2019, in many senses, was The Souvenir, the latest film from Joanna Hogg and the winner of the festival’s World Cinema Dramatic Prize. Hogg deepens the rich class- and site-specific renderings of her previous features (Exhibition, 2013; Archipelago, 2010; Unrelated, 2007) with the story of Julie, a well-to-do naïve young woman aspiring to make films, yet in danger of being consumed by a risky relationship. Pocket descriptions do injustice to the film’s mirror to experience, beautifully realized through a mix of soft portraiture and wide-shot interiors, with Honor Swinton Byrne disarming as Julie in her debut film role, Tom Burke playing out a mesmerizing slow-motion drug-hastened destruction as witty, caddish Anthony, and Tilda Swinton as Julie’s just-so mother.

Using journals, letters, even the first Super 8 footage she ever shot, Hogg entrusts the characters of her memory to the actors to “digest” (as she put it) and bring to the screen. (The film’s title is shared with that of a late 18th-century Fragonard painting which Julie and Anthony view at London’s Wallace Collection, depicting a woman carving letters into a tree.) The day after the acclaimed Sundance premiere of The Souvenir introduced this major contemporary filmmaker to new audiences, Hogg spoke with me in Park City about making the film, which will be released this year. The following is an excerpt from that interview.

You mentioned at the premiere that your own life was a starting point for the film but that things went on to be shaped into something new. Could you talk more about that?

It’s messier than I made out in the Q&A, in terms of the back and forth of my life and then what I’ve got in front of me. And there is really a point where I don’t know what was real and what isn’t. So it’s a real confusion of fact and fiction, and I enjoy that dance, but there are essential things that are true. I was talking with Tom [Burke] about how there’s some alchemical thing that happens, because I’m literally re-creating something: the flat is based on my own flat, and the characters are based on people I knew or myself. But then how can the actors know everything that’s inside me? Somehow I’ve got this image of a flat, packed thing that suddenly comes to life. There’s almost a supernatural thing of words springing from characters’ mouths that are true to what I remember in the past.

The initial meeting and dialogue between Julie and Anthony sketches out, in just three or four lines, an entire history of representing life experience in art. It’s interesting to see The Souvenir here at Sundance because it’s a place that always feels self-conscious about the notion of authenticity. What’s been your experience?

This is my first time here, but I’ve always had an image of Sundance as a space for independent American cinema, which is not what I feel that I’m making. So I suppose there was a thought of, “Oh, how will I fit into this world?” because I’ve always seen it in a particular way. Not negative or positive, but just different. Being here I’m struck by being in nature in a way, and then there’s the whole circus going on. If you’d asked me five years ago, “Where do you see this film appearing?” I wouldn’t have necessarily said Sundance. But now I’m here and it seems that some people are understanding the film. I’m really happy that it began here, because if it had begun in the U.K. or in Europe, then it’s sort of not anything new. And this is a very new thing for me, so that’s really exciting.

I find it wonderful the way you approach narrative, and the audience’s desire for narrative. When I’m watching your movies, I’m aware of what I’m expecting to happen, or even what I might unconsciously want to happen, and without making a show of resisting expectations, you’re often showing it’s not always about that kind of give and take.

Right, right. And does that mean that it’s sometimes disappointing in what it turns out to be?

No, no—for example, I often find in films where there is a character with some sort of substance addiction, the story gets attached to a certain arc. But your film of course is more dramatizing Julie finding a balance to her own life and self, and not letting that take over.

Yes. I recognize that I’m not following a story pattern, and it’s not that I’m consciously not doing that, but I’m very careful to not do something just for effect or because it’s what’s expected, or what even an audience might like. It’s got to be close, close to my own experience but also interesting to me in terms of something unfolding. I fell out of love with any kind of imposed structure a long time ago, and I’m really just trying to follow my own instincts. Sometimes those instincts may seem to be anti-dramatic. Or I see drama in small things.

When you’re working out scenes with your actors, and arranging and blocking shots, how does that all play out in the process?

It varies from scene to scene. For example, if they’re around a table, I’ll try them out in different positions and I’ll work out where they’re going to be in terms of the dynamics that are going on, so it’s very orchestrated. And then other times I’ll do a first take where it’s very rough and quite chaotic, which I enjoy, to start out with, and then it will get refined. But for each scene it really changes. With the [dinner] scene with Patrick, the film director, where Julie finds out about Anthony being a heroin addict, we decided that each take would be a different angle. So we didn’t try and do any continuity, we’d constantly shift, and because the flat has this big wall of mirrors, it’s really fun to play with that. Sometimes we’d shoot through the mirror, sometimes the opposite way, and we’d just constantly move around. I worked with a wonderful cinematographer for the first time, David Raedeker. And in other scenes, it would be just very simple, standing back. It’s fun to play.

You do something beautiful too with the view out of Julie’s apartment window facing the street, a view we keep returning to.

Yes, and that was a challenge and fun too, because those views outside the flat are based on 35mm slides that I shot in the early ’80s.

At the screening, you also said something about wanting to avoid nostalgia. This may seem obvious but could you talk about what’s wrong to you about nostalgia?

I suppose it can be sentimental, and sentimental to me is not very interesting, but I do feel very nostalgic about that time. When I am looking back and reading my diaries from that time and thinking about my ideas then and how I felt, I do feel a little pang of wishing to re-experience that in a way. I’m not saying I want to be 20 again, but maybe there are some parts of that which would be nice. So that’s the nostalgia, but I don’t want that to seep into the film. Somehow it’s like putting a veil on it. It’s not because I don’t want the emotion—I don’t connect to it with emotion now anyway—it’s just more a certain sentimentality.

For Julie, there’s a real urge to feel the right to tell her story. She keeps having to justify herself, like to those two examiners from the film school, and she keeps feeling like she has to justify herself.

It connects very much to my own experience, and my own experience of wanting to make this film. When I first thought about it in the ’80s, soon after I’d had this experience in a relationship, I didn’t feel I had the right to make the film. I had the thought of making it, but I didn’t think I had the right. It took me until a couple of years ago, when I decided to make The Souvenir, to feel like I had some kind of right to it. Even now, I’m still grappling with that, actually, because I somehow think it’s not just my story, and even though the other half, or the other story, or the other perspective, they’re not around anymore, there’s still a tension with that.

Where did it come from, the feeling that you could move forward?

I think it was just realizing that I didn’t have to tell anything accurately, that it could be my impression of that time and I can own that, and I can do what I want with that. And if someone else sees it who knew both of us at that time and says, “Oh, that wasn’t right, you didn’t get him right,” well, I think, to hell with it, this is mine. This is my view.

Right now I’m thinking of a scene in the film that recurs, when Julie makes a phone call off the studio stage where she’s filming or working—and when she goes back, the stage door always gets shut firmly and clearly. It feels like it’s sort of like what you’re saying—that’s the space of her art, and she can leave behind the rest and do what she wants there.

She can do what she wants, it’s true, yeah. And the story itself being about someone trying to find the right to make their own work.

At the end of the film, the credits announce The Souvenir, Part Two. Are you gathering notes for this next movie?

Yes, I’m writing that now, and we’re going to go into production in June.

Nicolas Rapold is the editor-in-chief of Film Comment and hosts The Film Comment Podcast.