Interview: Joachim Trier

This article, part of our coverage of NYFF59, appeared in the October 15 edition of The Film Comment Letter, our free weekly newsletter featuring original film criticism and writing. Sign up for the Letter here.

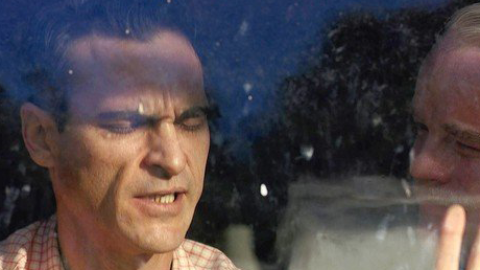

The Worst Person in the World (Joachim Trier, 2021)

In a prologue, 12 chapters, and an epilogue, Joachim Trier’s The Worst Person in the World follows Julie (Renate Reinsve, winner of the Best Actress prize at Cannes this July), on a journey through different versions of herself. She tries out medicine, psychology, and photography, and writes a moderately viral essay about “Oral Sex in the Age of #MeToo.” She doesn’t want kids yet, not when she has so much potential to fulfill. She turns 30. She sees herself through the eyes of two boyfriends: the older Aksel (Trier’s frequent leading man Anders Danielsen Lie), an underground cartoonist famous for a Fritz the Cat–like character; and Eivind (Herbert Nordrum), a young, environmentally conscious, and unambitious barista.

After excursions in genre filmmaking and America in Thelma and Louder Than Bombs, Trier and screenwriting partner Eskil Vogt return to Oslo and the character-driven work of their first two features. The Worst Person in the World is made in Trier’s characteristic freewheeling style, full of voiceovers, digressions, gags, and unexpected swerves. In the film’s two most striking sequences, the city becomes the backdrop, and Aksel and Eivind the opposing poles of Julie’s world. In the first, she crashes a party and meets cute with Eivind. The two decide not to cheat on their respective partners, but experiment with other forms of intimacy, feeling the intoxicating rush of meeting new people and trying on new personae. In the second, Julie imagines herself leaving the apartment she shares with Aksel and running to Eivind under the glassy high-rises of Oslo’s redeveloped harbor, while the rest of the city freezes in place. The sequence takes full advantage of the eternal magic hour of Oslo’s white-night summers, when it feels like the sun will never set—until, suddenly, it does.

I spoke to Trier while he was in town to present The Worst Person in the World at the New York Film Festival. Neon will release the film in the U.S. this winter.

I know you’re interested in George Cukor, and the first thing that came to mind in relation to this new film was Holiday—the idea that you could meet somebody, and see in them the possibility of a new version of yourself.

I think the best romantic comedies use the negotiations of getting close to another person as springboards for existential questions about how we define ourselves. And how painful that negotiation can be, and how funny, hopefully, but also how existentially important it is. For example, in The Philadelphia Story, there are different existential pathways, or aspects, of Katharine Hepburn that she’s negotiating to try to find a sense of vulnerability in herself. To be able to experience love, you need to experience the loss of your idealized self, in a way. In the middle of one of the funniest, most loving films we have, there’s an essence of something quite serious.

The starting point for my film is the rom-com, but over the course of the the film, it becomes a more existential pondering about the idea of self, and time—how limited time is. Unless we recognize that, we feel that we have this sense of infinite time. That’s a very chaotic place to exist—but also a very romantic one, and I sympathize with Julie, who is 30 and still feels like she’s not grown up.

Your films are often digressive and structurally heterogeneous, but in Worst Person in the World, that’s more character-motivated: you’re telling a story about someone who doesn’t know who she wants to be, and you’re telling that story in a number of different ways.

When Eskil Vogt and I write together, we don’t start with plot at all. We start with character, theme, and a third component—what you’re asking about—that we call “concept scenes.” For example, we ask what might happen if, in Oslo, August 31st, someone were sitting in a café, with the dark mindstate of a recovering addict, listening to casual conversations from many people at the same time. Or in this film, we play with the metaphor of wanting to escape time to experience an alternate version of love—finding formal ways to do that, and letting form be a fun, involving, playful mechanism rather than an alienating, cold one. The idea is to use the language of cinema to be as free as the character Julie, who changes her identity every five minutes.

Many years ago, I had an idea: someone who’s in a relationship meets someone else and they immediately realize they are attracted to each other. But they say, very clearly, “We can’t be unfaithful. So what else are we allowed to do?” Then I realized that could be a meet-cute, in the classical rom-com sense, to have two characters play that game. Eskil and I have a drawer full of strange formal ideas, but we can’t really use them until the characters breathe life into them and they make sense as part of a whole. The film was originally much longer. I like the version we have now—I have final cut, and it’s made the way I want—but there are many digressions and ideas we had to leave out. So we found the film along the way as well.

Was it always the plan to tell this story in twelve chapters?

It was full of chapters. We thought, to create a story that bleeds through time and follows someone from their late twenties to early thirties, we needed an elliptical structure, which gave me the freedom to go deeper, beat by beat. The one note on the wall of our writing office, that stays up there between projects, says, “Remember contrasts.” That means contrasts in characters’ behavior, and in the tonal shifts of a film. It’s a film about light, silly romanticism, on the one hand, but also it’s a film about mortality and the importance of loss to being present in your own life.

Because the story is told elliptically, we know there’s stuff that’s been left out, which makes it feel more like time has passed.

And it’s a film about time, ultimately. It also hopefully leaves space for an audience to engage it. I wanted to make a warm embrace of a film, and I want there to be hope in it even though it’s quite sad at times. An important guide was Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own. Julie needs to find a space of her own, where she can tolerate herself and not escape through the contact of others.

I wanted to ask you if it’s more difficult to write a character who is inconsistent—or if you reject the idea that there’s anything different about her relative to other characters you’ve written.

The most fun part about writing this film was the chaotic inconsistency of the character, who is held together through Renate Reinsve’s amazing performance. I knew I was writing it for her, so I knew I had someone whose emotional center would be one of the most intriguing I’ve been able to portray in a film. Having that perspective on the idea of self—in a comedic sense, not in an analytical sense—through a character who’s constantly escaping consistency was fun, and that itself became the consistency. It’s also about her realization that some periods in life seem like temporary stages, before she realizes how little time she has and that some of those seemingly temporary things are actually the essence of who she is and what she experiences. I guess that’s what it means to grow up. It’s a film for grownups who still feel like they don’t know how to grow up. I know a lot of those; I think I’ve felt that in my own life.

When I wrote this film I needed to make something hopeful and joyful. I felt that Oslo, August 31st was trying to take people into a space of acceptance of sadness and grief, and that the catharsis had to lie outside the story. Whereas here, I’m older, and I wanted Julie to end up, regardless of the pain she goes through, in a place of self-love. It sounds like I’ve become an old hippie, and maybe I have. Freedom is hard—I think we all feel that sometimes, and that a fragmentation of self is at play in our lives more than it has ever been. We’re given this illusion of choice, but at the end of the day, our time will only be this long, and that knowledge can create a fear of making choices. You think that all the doors are open, and before you know it choices have been made for you, because you didn’t make any. I think that that chaos has a lot of humor in it.

I want to ask about the Oslo geography—when the city freezes and Julie runs to Eivind, she moves between two eras of the city, or ways of being in the city.

I’m trying to map out a journey. In the beginning, she lives in a formerly-bohemian-but-long-

The film is about to come out in Norway, and I’m being invited to do a lot of panels about city development, as if I were a sociologist. All I know is that this street and that house create an emotional space for the characters that I can convey, though I don’t know what it means in sociological terms. I just know that these things strike me intuitively. That’s the wonder of writing about your own town. It’s my view of Oslo, just as the New York of Scorsese and the New York of Spike Lee are quite different. They’re both portraying the same city, but are different interpretations, which are beyond words. That’s the great thing about cinema—it’s closer to documentation than to analysis.

Mark Asch is the author of Close-Ups: New York Movies.