Interview: Jim McBride

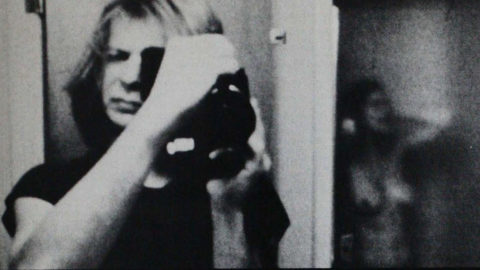

Building on the work of pioneers like Jean Rouch in France, the American Lionel Rogosin (On the Bowery), and others, politically virile documentarians in the Sixties preached the tenets of unfiltered cinematic truth. In 1967 David Holzman’s Diary arrived as a sui generis, witty corrective to all this truth-telling: a hoaxed blast of “reality” whose main subject is the impossibility of objective documentation. Directed by Jim McBride, the film purports to be the diary of David Holzman, played by L.M. Kit Carson as an insecure, energetically curious young cineaste who sets out to film his life and those of the people around him, hoping in the process to attain a new level of pristine authenticity.

The lamest possible criticism of the film is to decry its false notes. David Holzman’s Diary shows its hand often, but that’s only part of the point and the gag. David’s friend Pepe (Lorenzo Mans) echoes one possible reaction when he says the diary is “not believable… It looks like a horrible movie… Don’t make me look at it on the screen,” and it’s as funny as anything in Albert Brooks’s like-minded proto-reality-TV spoof Real Life, which came a decade later.

FILM COMMENT spoke with McBride about his classic and his shift to Hollywood filmmaking. David Holzman’s Diary plays in Film Forum’s New Yawk New Wave series, paired with Coming Apart (which is directed by Milton Moses Ginsberg, also a friend of McBride’s who edited two of his movies).

David Holzman’s Diary

How did the idea of David Holzman’s Diary develop?

I had a lot of interest in cinema verité. It was a very exciting time because there were several things going on in movies and in New York at the time. Some of it had to do with documentary and these new technical abilities to shoot with a relatively lightweight camera that made it possible to show real situations. You could film without disrupting things too much. With that new kind of filmmaking, it became possible to get in touch with the real. There was other stuff too—the French New Wave, the American underground. If nothing else, they made the idea of making movies very exciting. We were all trying to find another way of expressing something that was different from the standard Hollywood movie fare. That’s how I got interested in movies.

With David Holzman’s Diary, Kit [Carson] and I were doing a monograph at the MoMA about cinema verité, and we interviewed a lot of the major people who were doing that, like D.A. Pennebaker and the Maysles Brothers and a lot of others. There was this general feeling or idea that there was this kind of truth that could be revealed that had never been revealed before. This was very enticing to me, but at the same time it was also silly, the idea that there is some kind of objective truth that can be revealed. And so I got this idea to make a film about a guy who thought he could find out the truth about himself and about his life by filming it, and not succeed.

Did you think of it as putting the idea of cinema verité as promoted by those filmmakers in your crosshairs, or was it a less aggressive thing than that?

I don’t want to denigrate those guys’ achievements. I was a big fan of theirs both personally and in terms of the films they made. It was more the idea of truth that seemed so elusive to me.

So the style wasn’t necessarily a satire of any particular filmmakers.

No, not at all. Except David Holzman himself.

Godard is often cited in writing on David Holzman’s Diary, and is also quoted in the film by Holzman. What was his influence on you?

He was a huge influence. I’m not sure how I could directly ascribe it, except of course in the quote about film being “truth 24 times a second,” where you find a recurrent theme in not just the movie but in the world of young movie enthusiasts. I’m not even sure Godard believed that when he said it. It’s hard to know what he believed whenever he said anything, but he was very good at coming up with provocative statements. He was a—I don’t want to say godlike figure, but he was a crucial figure to anyone who wanted to try something new and break the rules and go in the street and film life as it really was and not some confectionary thing created by some kind of mass medium. It wasn’t his politics or his sort of determined experimentalism that excited me. It was his exuberance, his wanting to try something new and succeeding that was so thrilling and encouraging to young people like me.

Were you close with other New York filmmakers at that time, or did you run with your own crowd?

There was a kind of a crowd. We didn’t all hang out together, but a lot of us knew each other. I went to NYU and was in the same class with Marty Scorsese, and when he was doing Who’s That Knocking at My Door and I was doing David Holzman’s Diary, we were both working with the same cinematographer, Michael Wadleigh. Mike had a little facility that he ran. He hired himself out. And we both had adjoining editing rooms at Mike’s place. Who else? I knew Brian De Palma, and also somebody that hung around was Jonas Mekas. The Anthology [Film Archives] didn’t exist in those days but those same people were running screenings all over town in people’s lofts, basements, stuff like that. There was something called Cinema 16 where they showed experimental movies. It was a great, not a movement particularly, but it was a great time for movies in New York, and people who were turned on and enthusiastic about that kind of stuff tended to find each other.

What was Michael Wadleigh’s contribution to David Holzman’s Diary?

In some ways he kind of made it happen. First, he was the cinematographer. I worked for and with him as a soundman and editor when he would do commercial jobs. It’s kind of a complicated process, but we would go out and shoot something for somebody and if he had to shoot something on the following Monday, say, we’d keep the equipment over the weekend. So Mike’s idea was, this movie you want to make, why don’t we just use this free equipment we have on the weekends and shoot stuff. So that’s what we did. We used leftover film stock. To process the film we would go to the lab under the aegis of some other project we were working on.

He made all that happen, so that was his role. He was not only a great cinematographer, he was a great enabler. He was also a genius with the camera. He had a really unique way of looking at things. I consider his work to be some of the best stuff in movies. David Holzman’s Diary was a collaborative enterprise between him, me, and Kit Carson. It’s hard to say where one person’s influence started and the other’s ended.

Beyond its fascination as a meta-documentary and its funniness and pathos, David Holzman’s Diary is a great time capsule of 1960s New York City and the Upper West Side. Was it a conscious intention to capture so much of the local flavor and people for posterity—like the great shot of the park bench old folks in Verdi Square—or was that a quirk of the Holzman character?

That was my neighborhood. I was born and raised there and I still lived there, not with my parents but I still lived in the neighborhood long after I left home and so these were the streets that I walked, these were the things that I saw. There was a feeling that you didn’t see these things in movies, so it was kind of my world and I wanted to share a little bit.

When it comes to that scene you mention, that was a scene I would pass every day on my way to the subway, and at some point we had the camera and I told Mike I wanted to shoot a shot walking past all these people. I didn’t really have an idea beyond that. He made the shot really work in kind of a brilliant way. Instead of walking along pointing the camera at them while looking through the viewfinder, he sort of cradled it in his arms, so it was pointed off to the side. It was also at eye level with the people as he was walking by. He was walking forward and the camera was looking off to the side, so people didn’t realize he was actually filming them.

Some of them are giving him an evil eye, but others don’t seem to notice.

Right. And also we sped it up a bit so it had a kind of odd motion feel, and we used a wide-angle lens on it. All of those elements combined to make the shot really work. My idea to do it was just something that I’d seen that I longed to get on film, but Mike turned it into something memorable.

There’s an intriguing juxtaposition with what’s on the soundtrack—a roll call vote at the United Nations.

Right, right. That came after, obviously.

It’s a great moment when they appear, and you had to give recognition, but did you ever consider not putting your names on the credits? To maintain mystery.

[Laughs] No. I think we all wanted it known that it was all a rook, and not until the end.

Do you have a preferred pigeonholing term for what David Holzman’s Diary is? I’ve heard a lot, like docufiction, mockumentary, meta-doc, pseudo-doc, etc.

No, I don’t. I call it my movie.

One of the most powerful and uncomfortable scenes in David Holzman’s Diary is Holzman’s filming of his sleeping naked girlfriend, Penny. What is your moral judgment of that act, or do you not presume to judge?

That’s an interesting question and I’m not sure how to answer it. I don’t consider a moral dimension for myself because, you know, it’s a fiction, we set it all up. But obviously he does it with a strong sense of guilt, and she takes it with a strong sense of betrayal. I don’t know how someone could not, intruding into one’s privacy in the strongest kind of way, just because someone is available. The morality or the immorality of what he was doing really had to do with his own personal conception of what he was doing. He knew he was doing something he shouldn’t have been doing.

The David at the end of the film would probably not do it. The character really travels an arc.

He didn’t necessarily learn the things that we think he should’ve learned.

The montage of television frames over the course of a night is both eye-opening and a little depressing. Was it created in the way that Holzman describes it?

Yeah, I actually did that myself with a little Bolex camera and a tripod, and just shot in front of the TV, clicking off one frame at a time.

My Girlfriend’s Wedding

My Girlfriend’s Wedding [69] seems completely like an answer film to David Holzman’s Diary.

Like a stupid answer, I guess. [Laughs]

Really?

This was some time after David Holzman’s Diary. Mike Wadleigh was getting involved with some people who wanted to create an alternate distribution network to distribute films and release films like Holzman’s theatrically, films that weren’t part of the mainstream and didn’t really have the possibility of being seen in theaters in those days. They wanted to distribute Holzman’s, but they felt it was too short to actually fill a program. So they gave me a small amount of money to make a small film that could go with Holzman’s on the same program to fill it out and make it two hours or something like that. I said sure. It just so happened that I had met and fallen in love with the woman in the movie, and she was basically this yippie and so she seemed like the perfect thing to go out and film, particularly with the limited amount of money they were offering me. We could basically do it in one day. So that’s how that came about.

Why was Pictures From Life’s Other Side [71] suppressed?

You know I can’t really tell you. It’s not a secret; it’s just that the person at the AFI who was administrating the program while I was editing it was different from the one who gave the grant. This person came to see a rough cut while I was finishing it in northern California, where I was living, and she absolutely hated it. She didn’t even want a print of it. Finally she allowed a print to be made but not shown anywhere, and I didn’t have the money to show it on my own. It got buried in the vaults of the AFI for many, many years. Several years after that, I went to work for the AFI as a teacher, and once I got comfortable there I tried to get the librarian to find the negative and they never did. They lost a lot of things at the AFI [laughs]. So that’s the saga, for what it’s worth.

How did you effect that transition to big studio movies in the Eighties, from Hot Times in 1974 to Breathless for Orion in 1983?

Hot Times is just sort of something that came out. I ran into this guy I’d been in the third grade with whose father was a producer of softcore porn, and I needed a job. It turned out that they were about to make a movie and I got to make it. It’s a longer and more complicated story than that. I was very happy to be able to actually make the movie and it was a lot of fun, and that was in New York. The reality is I just wanted to find a way to continue to make movies. The bottom had fallen out of the independent film market and nothing was happening, so at some point I just decided that I was going to try my luck in Hollywood. I came out here, and I’m still here. I had to learn how it all worked here. I got to make edgy films but I never really figured out how to fit in.

The idea of Breathless came about kind of capriciously. There’d been someone I knew who knew Godard who put me in touch with him and… There are a lot of stories involved with it, but everything just sort of happens haphazardly. You know, we found a producer, and it took five years to get the film made. In the end it was all about finding a star who would be in it, and Richard Gere was that person. As I say, it’s a very long saga.

Right, I figured.

[Laughs] That’s how it is with any film. Certainly any film I made has a saga attached, though I haven’t made very many.

Breathless

I am a big fan of Breathless. Was it conceived as a dialogue with the Godard film or its own separate thing with separate ideas?

I would call it an exploitation of the Godard movie [laughs]. Look, I was a huge fan of the original film. If it was only one thing, then Breathless was the thing that made me want to make movies. But in reality, the chance to make a remake of this film that I loved so much came up rather accidentally, and once it was going to actually happen it seemed to me ludicrous. I felt terribly embarrassed! I was really just taking advantage of an opportunity that gave me a chance to direct a movie. Of course, as Kit Carson and I were writing it, it grew into its own thing.

I will say we went out of our way to try to tell the same story with the same characters, but in a very different, more conventionally Hollywood kind of way. When we were writing the script, I found a copy of a French magazine that used to reproduce screenplays of films that they thought were important. They had the Breathless screenplay and I actually translated it into English and then worked from that as we started to write our screenplay. As it went along, we’d drop things and add things. Things change every step along the way, with casting, choosing locations, finding the cinematographer. Each situation changed it, and by the end it was something very different from the original, for better or worse.

Changes in technology and the rise of found-footage and so-called reality television since David Holzman’s Diary seem to have only further obliterated the meaning of “truth” in film. And objects like Zero Dark Thirty toe that line in their own way. Any thoughts on the current state of cinema verité in documentaries and feature films?

I really like Zero Dark Thirty and I think it’s getting a bad rap, in the sense of people talking about its trying to imply that torture was the only reason we were able to get bin Laden. Which I don’t think it’s saying at all. I think it’s just saying, here is what we think happened, judge for yourself. And I think in that sense it’s extremely well done and tries to tell its story in as uncharged a way as it can.

As far as the other stuff… When I made Holzman’s, My Girlfriend’s Wedding, and Pictures From Life’s Other Side, I was obsessed with these ideas about what’s true and what’s not true, and more just how to be honest about yourself and your own life, things like that. But I’ve long since lost interest in that. I just haven’t followed the people who are doing that kind of stuff. I became much more interested in various other kinds of narratives and most of my so-called career has—even as a teacher—been about how to tell stories with images. Back in the day I found reality more interesting than I do now. It’s just not my inclination.