Interview: Ishmael Reed

Personal Problems is among those rare, quietly unassuming avant-garde works that takes the trouble to be genuinely entertaining while pushing formal and textual boundaries. Based on a treatment written by Ishmael Reed—the canonical Neo-Hoodooist novelist, playwright, poet, and icon of the Black Arts Movement—the script of this experimental soap opera evolved through rehearsals and improvisation by actors Vertamae Grosvenor (author of Vibration Cooking and an actress in Daughters of the Dust), Walter Cotton (playwright of New York City Is Closed and an actor in Cotton Comes to Harlem), and Jim Wright (a veteran of 1930s race films). Originally available as a series of cassette audiotapes put out by Reed, Cannon, and Johnson Communications Co. in 1977, the recordings aired on assorted radio stations across the country. Thanks to an NEA grant, it became a two-volume video program for PBS directed by Bill Gunn (writer/director/star of 1973’s Ganja & Hess) and photographed by Robert Polidori.

The first volume opens with Johnnie Mae (Grosvenor) in her nurse’s uniform being interviewed by Gunn (off-screen), reflecting on her youth in South Carolina, problems with her mother, and how she’s unhappy in Manhattan. From this meta-textual description of her “personal problems,” we’re haphazardly delivered into them: Johnnie Mae gossiping with her friends at brunch, spending quality time with a man who isn’t her husband, exasperatedly cleaning up after her family, and on her rounds at Harlem Hospital, tending to a young man (also originally from South Carolina) who has been shot. The second volume briefly re-presents these glimpses of her life in chronological order, and then moves into showing yet more struggles: her father-in-law (Jim Wright) passes away, her visiting brother, Bubba (Thommie Blackwell), is sent to jail, and her musician beau (Sam Waymon) breaks up with her. Presented at the speed of life—no fast cuts, no jumping between spaces—the leisurely pace of Johnnie Mae’s drama sneaks up on you, twists, turns, and then becomes something entirely different.

Despite the degree of talent assembled, Personal Problems failed to be picked up as a series in 1981, the ¾-inch U-matic videotapes it was shot on languished in Reed’s attic. Thanks to a new DCP restoration by Kino Lorber, Personal Problems is no longer limited to breathless descriptions by excitable film scholars: it opens today at Metrograph in New York in all its 165-minute, ghosting glory. I spoke to Reed, 80, who produced this remarkable project, last week in TriBeCa. Representation, the tradition of the race film, and politics naturally came up.

You wrote the original treatment for Personal Problems. Were you around for the rehearsals and improvisation sessions?

I ran it from California, sent in suggestions, and you know, we collaborated. It was a collective effort of Steve Cannon, Walter Cotton, and I. I had written treatments before for film—people had optioned my books to be films. So I’d pass those treatments along and we’d talk about it. It was mostly improvisational, based upon a skeletal storyline. The late Walter Cotton and I were producers, and it’s sort of like a Walter Cotton family reunion, because he’s got his daughter in there, he’s got three or four members of his family in there. He paid the actors, he paid the crew, he was a good administrator. Because of his contacts in the theater, he was able to give us great actors. Barbara Montgomery and all those other performers came because of Walter Cotton. I chose Vertamae [Grosvenor], I chose Walter, and I chose Joe Johnson, who I think was the one who suggested Bill Gunn. Kip Hanrahan, who produced a lot of my CDs, Conjure and all that, he got us Robert Polidori.

So we had all these people, young people at the time, nobody knew what they were doing. Personal Problems was rejected by PBS in Washington because this woman who was a big muckety-muck didn’t like the style of Bill Gunn’s work or Kathleen Collins’s. She said, “You guys don’t know what you’re doing.” Boy, that was humiliating because I brought Newsweek, big people who had covered my novels in there. And now Bill Gunn has a cult following. Carman Moore is an internationally famous composer, worked with Meredith Monk, did all this stuff. Robert Polidori had work at the Palace of Versailles. So all these people came forward, later on.

Your play Mother Hubbard was also filmed around this time, but there was a problem with the sound, correct?

What happened with Mother Hubbard was that there was a non-profit equipment sharing facility in San Francisco, and they insisted that we take their sound person. The sound was messed up, so they had to pay us a settlement, which was very much less than our original budget. KQED in San Francisco promised to do it, was committed to doing Mother Hubbard. And then they reneged. I don’t know what it was—it was never explained to me why they backed out. But we finally got [Mother Hubbard] done in China. It’s supposed to be a totalitarian state, but we did it there, and we also performed it at the Nuyorican Poets Café [in 1998]. Mary Wilson of The Supremes had seen a production and asked for a part, so it’s got a history.

As you were producing Personal Problems remotely, what was your working relationship with Bill Gunn like?

We gave him free rein. It was his film—or, I should say, video. My whole thing was not to intrude. I had very few conversations with him. I sent him a fruitcake for Christmas, I remember that.

The beginning of Personal Problems is so wonderful, when Vertamae Grosvenor talks directly to the camera, interview-style, and it’s unclear if this is a documentary or fiction. It evokes the writing and anthropological work that Zora Neale Hurston did, while also referring to this “burden” in black art where it has to have this “authenticity” or documentary sort of quality to it. Where did that choice of style come from? From these improvisation techniques?

No, [the cast] created the characters—which is the definition of race films, where blacks delineated themselves. They had black producers, black directors. At the time, we were not aware that we belonged to that tradition, and even more accidental was the fact that we had Jim Wright, who appeared in one of the last race films, and was in Orson Welles’s Macbeth at the Federal Theatre Project. Those films were wiped out because the equipment became more expensive, and they were always under-financed. Many stopped being produced with the introduction of sound, although YouTube and Netflix have preserved some. So we’re part of that tradition. These characters defined themselves. It wasn’t like The Color Purple where it was all white guys. I mean, it’s ironic: the producer, the writer, and the director for The Color Purple were all white guys. That’s like the British writing about the Irish famine, or one of the Apartheid prime ministers doing the Nelson Mandela story.

We wanted to have independence, which I learned in New York. I was part of the downtown art scene in the ’60s, and I learned from both the counterculture and the cultural nationalism. For example, Walter Bowart and I had done an underground newspaper [the East Village Other] and he found a Chinese printer who was able to print it for practically nothing. So I learned those techniques down here [downtown Manhattan] that you could do high-quality work with the least budget as possible.

It’s been a long battle, even before Birth of a Nation. A lot of people said that black people protested Birth of a Nation, but Oscar Micheaux and some other filmmakers answered it with their films. A Day at Tuskegee was in 1913, for example. So they were making films, not just protesting. There were many companies doing this. But those uplift films went to the other extreme—they show people who are too good and respectable to be true. I’ve read several accounts of race films, and there were 500 made, but only 100 remain. We know about them because of clippings or contemporary research, but they were lost. And I think that’s what would’ve happened to those 54 tapes [of Personal Problems] in my attic. It was Jake Perlin who brought this back with screenings at BAM and [the Film Society of] Lincoln Center, and then Bret Wood saw it. Now we have this restoration that’ll be around for a while. It can tap into a global audience, which have probably never seen these types of blacks in American movies before.

The prestige mode in films dealing with race still continues to this day, where the focus is on the exceptional and the “uplift.” It is weirdly regressive.

And some of these films that are produced in Hollywood are worse than The Birth of a Nation. As a matter of fact, in comparison to things like The Color Purple—I was left as literary roadkill because I didn’t like that movie, but Alice Walker didn’t like it either, and even criticized Steven Spielberg’s treatment of misery… bell hooks said Hollywood takes these black feminist products and make the black men even worse than how they appeared in the novels.

Tablet asked me to write a piece about Alice Walker boycotting Israel three times. One of my ex-students is an editor there. But I was not interested in that—I had been to Palestine—so instead I challenged Steven Spielberg to make a Jewish Color Purple. I read Tablet, and had seen an article written by Jewish-American women who pointed out that that Jewish-American women aren’t given roles by Jewish-American producers—they were more likely to give a role to Mariel Hemingway than to the Jewish person it was intended for. So in my article I asked: who’s going to play the role of Celie in the Jewish-American Color Purple? It would probably be Nicole Kidman or some WASP. Tablet ended up turning it down. But that’s one of my critiques of Hollywood: the same group of middle-aged white guys are talking about the youth, or about women, or gays, and it’s like they own the narrative. The black narrative in this country is occupied. It’s a colonial situation where they define us.

You can see that in the way the media treats the Parkland teens versus teenagers who were out protesting in Ferguson: the Parkland kids get a Time magazine cover shoot and the Ferguson kids are made to look like they’re criminals or guerrilla fighters. This mediation is made worse by social media where these white, middle-aged men think that they can peer into someone else’s experience and understand it. No, you actually have to talk to people and involve them!

That’s true. I saw this thing last night on television on Martin Luther King’s relationship to the media and it was narrated by this white guy. Half the people who are commenting were white guys! They didn’t get the irony that the same situation exists today, where they interpret our stuff. They even had Chris Hayes on, who wasn’t even born yet. He has an easier time getting published writing about black issues than black scholars, or the people who actually worked with King. So it’s a struggle, not only for us but for women. We have Denzel Washington and women have Meryl Streep or Nicole Kidman. There are tokens.

With digital technology and the success of something like Moonlight, do you feel now is a time when black arts can really blossom again?

Oh absolutely! I mean Amiri Baraka is one of the pioneers of doing low-budget films and low-budget record albums, things like that, and that entrepreneurial creativity that went on downtown here. In the West Village, people were drinking whiskey and reading Malcolm Lowry’s Under the Volcano. On the East Side, we were all working-class, white and black, and we were producing things as well as writing and whatever else we were doing. I asked Robert Polidori about the equipment that he was using back then, and he talked about how he made cuts using ¾-inch tape and everything. I asked him what kind of equipment he would use nowadays—and I just looked all this stuff up and saw that you can rent an $83,000 camera for maybe $1,000 a day. There’s no longer a need for people to be begging Hollywood for Oscars. Those people are not going to change. Fortunately there were like 125 black film companies that didn’t wait around for Hollywood to act right. Once in a while they’ll do something like Black Panther—I haven’t seen it, I’m just suspicious of a film where Walt Disney and all those people cut all the checks.

I wanted to ask about the representation of crime in Personal Problems, because you have been very critical of things like The Wire and this Hollywood tendency to dwell on “black on black crime.” How did the storyline with the kid who was shot arise?

I think the comment that Gunn was making with [the man who was shot] was that people in underserved communities have to go through a lot of red tape in order to get health services. I recall that one of the last episodes of Seinfeld—I didn’t really follow that show—was about some guy who refused to assist someone who was in trouble, and a few days before that a black kid died in front of a hospital because he didn’t have insurance. Now the kind of stuff that these characters [in Personal Problems] do, like bad checks and that kind of stuff, that’s mild in comparison to portraying the black community as the location of all drug dealing. Now we find that wasn’t true, that drug addiction is widespread. Of course, the media, since it’s run by white patriarchal guys, has a tendency to let whites off the hook. I have collected clippings about heroin addiction in the suburbs in the 1990s, and now they try to pretend that it’s a new thing. They just covered it up. If you go back to the 1990s, you’ll see heroin in the Philadelphia suburbs, but it’s got 200 words in the back pages.

Those in charge of the media have historically felt that there was entertainment value in showing blacks as criminals. Although you have these characters like Bubba and the guy who was shot, they’re overwhelmed by middle-class blacks. Compare that to Precious, a Hollywood production, where all you have is blacks cheating the welfare system and stealing and so on—it’s like Ronald Reagan wrote that script. A friend of mine, Diane Johnson, who wrote The Divorce and some other things, said that The New York Times, largely read by white audiences, loves to peek into black communities see if the old guy is sleeping with his daughter and all this kind of stuff. So there’s a commercial value in that, but we tried to balance that with the portrayal of all these people who have jobs—that kind of lower-middle-class couple, which I’ve known ever since I moved back into the inner city in 1979 up until now. Those people have been my neighbors: people who had two jobs. Although there were crack houses on the block, there are also people working every day and kids going to college, and that’s kind of the variety we wanted to show.

And the wake scene, where Johnnie Mae’s daughter is just standing there silently, is so incredible—just the way the dramatic structure works.

That was my idea to open up with a funeral, and by coincidence, Jim Wright died. I feel really bad about that—some people were complaining about his performance, and I said flippantly well maybe we ought to open up the second episode with a funeral, and then the poor guy died. The wake scene is very powerful. I’m disappointed that all the people involved are deceased. I had to wait 35 years to hear what they were saying in that scene, because of the bad audio track.

Were other parts lost to you before the restoration?

They’ve done a great job with the restoration. We didn’t have any money. No one had any money, and nobody was gonna make any money. It was kind of typical below 14th Street, Lower East Side production. People were thinking about quality and breaking taboos. At that time, a dark-skinned woman—this is historical, if you look at black films made by blacks, they prefer light-skin actresses in the lead, and Vertamae Grosvenor was certainly not that. She’s not your typical lead, not your Nicole Kidman or Halle Berry, you understand. And then Walter, he was not black enough. It was difficult for him to get a role that matched his talent. For example he was in Cotton Comes to Harlem. They shot a whole scene with Walter and they cut it, which was fortunate for him because it was a terrible film. As a matter of fact, Chester Himes, from whose novel it was adapted, called it a minstrel show. He hated that movie. But that was the kind of problem Walter had.

There were supposed to be more episodes. Could you talk about things that were planned that didn’t end up happening?

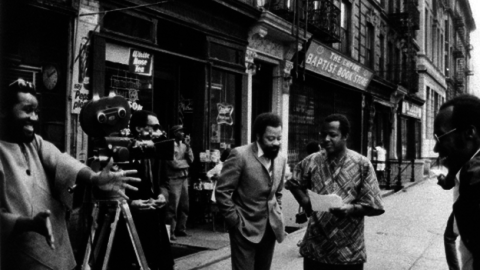

WNYC wanted to do a series, but I think Personal Problems ended where it should’ve ended, with those beautifully photographed Central Park scenes. When Bill Gunn died, I think that took a lot of momentum out of the project. We wanted to do another episode with Calvin Lockhart, and as a matter of fact there’s a photo of us walking out of the New School with Calvin—Walter, Bill, and myself. We had the cognoscenti—the black cognoscenti—at that screening at the New School and nobody was prepared for it. It was a hybrid, it was long, and it was like everyday life—things going on at a leisurely pace. A lot of life is boredom, and so Bill wanted to include all that. I think he said he was influenced by French filmmakers.

In Personal Problems, the first episode is scrambled up, and in the second episode you see the actual chronology of everything and then you understand everything in a completely different way and then it moves into this other stuff. Was that more a Bill Gunn thing, or was that what you had originally intended?

The first episode was 30 minutes, shot by Bill Stevens’s company, and done in a single interior with an atomic meltdown in the background. That’s the first one, it’s 30 minutes. And then we brought Bill Gunn on, to do work with Robert Polidori. I think Bill Gunn was in that first one too as an actor. We didn’t use Bill Stevens for the subsequent ones. But I suggested to Kino that they take that one monologue from the Bill Stevens version—the monologue featuring Sam Waymon—and put it in this final version, and they did that. Cause you had a monologue from Vertamae’s character, and what was missing was Sam Waymon’s monologue. They did a great job. I never could understand that whole scene in the bar, after the wake and the four characters are out walking around, because the sound wasn’t good enough. But now you’re able to hear the dialogue and it’s excellent.

I know that your company originally published Bill Gunn’s Rhinestone Sharecropping and Black Picture Show, and both are now available through The Film Desk. Do you have any plans to release the original Personal Problems audio cassettes?

They’re at the University of Delaware archives, but not commercially available. It’s a good idea, though. Maybe we’ll do that down the line. Because the audio versions are very, very good.