Interview: Frank Vitale & Stephen Lack

Montreal Main (1974) is the sort of work that justifies the existence of the independent filmmaking endeavor more often dedicated to the creation of calling-card movies. It’s too raw and discomfiting and morally dubious to be made by anyone other than committed amateurs with nothing to lose. It was the work of young Anglophone bohemians living in French Canada—director Frank Vitale, Allan “Bozo” Moyle, and Stephen Lack—all of whom appear in the movie playing variations on themselves: Lack a motormouthed hustler, Vitale and Moyle two roommates questioning their extra-close platonic relationship, which comes to a crisis when Vitale’s character embarks on an unusual friendship with the beautiful 12-year-old son of some friends.

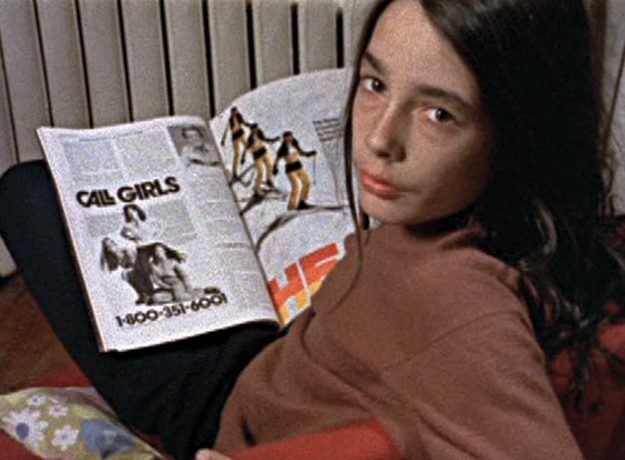

The trio would continue to work together over the next few years, on Vitale’s 1976 exploitation effort East End Hustle, in which a Montreal ex-prostitute and procuress turns her onetime employer’s stable against him, and The Rubber Gun (1977), the directorial debut of Moyle (Pump Up the Volume, Empire Records), shot by Vitale and starring Lack as a Montreal drug dealer and Sunday painter who quits crime in order to rededicate his life to art—just as Lack himself would back away from acting after starring in David Cronenberg’s Scanners in 1981, by which time the collaborators had drifted apart. But when Vitale and Lack were reunited for Anthology Film Archives’ “1970s Canadian Independents” series in March, Film Comment was on hand to speak to them about their classic projects, and the creative ferment of Montreal in the 1960s and ’70s.

East End Hustle

So Frank, how did a Jacksonville, Florida, guy wind up in Montreal?

Frank Vitale: Well, I went to school at McGill. I started in ’63, finished in ’67, studying physics. It was very inexpensive and exotically far away. And it was a quality education. I met Steve when I was a senior. After graduation I moved to New York and started working for fashion photographers, and gradually moved into film production. I was kind of an organized guy who could get things done.

Stephen Lack: You worked for John Avildsen, right?

FV: Yeah. I did three movies with him, as production manager, line producer, production assistant. I was still in Canada a lot, though, and there were many artists there that I envied what they were doing. So I wanted to make my own film, and I kind of knew how to put it together.

Stephen, had you been studying art at McGill?

SL: No. McGill had only one studio course, and in that course I met two Americans who were friends with Frankie, and they introduced us. But because I was a local boy, a Montreal Jewish kid, I didn’t fraternize with the Americans, even though there were five in my fraternity, ZBT [Zeta Beta Tau]. So it was the art class that brought me together with these two guys, Marty King, who has disappeared, and Henry Stoltzman.

FV: He disappeared, too.

SL: Yes he did, because we don’t know what’s on the other side of the veil. That’s where he went. I don’t want to give you too many goose bumps, Frankie, but after we met, I left Montreal to go down to Mexico to get a master’s degree in sculpture. I had a dream there that you and Marty picked me up in a Volkswagen van at the Sunoco station where Circle Road and Queen Mary meet. It was not unlike a scene [in Montreal Main] when you’re bumping into Bozo, you kind of run him over. And then when I came back in ’68, you were on the Main. But I was still running around, I hadn’t finished my travels. In ’69 I went to Europe, and then when I returned, Frankie was living with and sleeping with half of the girls that had been in my art class.

And Allan “Bozo” Moyle was also in your circle at McGill?

SL: Frankie legitimized the fact that I would know Al. I wouldn’t have talked to somebody like that. [Laughs] Allan always had an agenda. Like, “I am having a party… I need your records. I need your loft. I want you to bring six people. I want a list of your favorite books.” It took me a while to get used to him. But Frank was a gentle, very large spider. He’s calm. He’s being interviewed and I’m doing most of the talking.

FV: No, we’re both being interviewed.

SL: Okay. I talk, and you brood!

FV: Did you know that Allan has a part in Avildsen’s second film, Joe [1970]? I worked on that [as unit manager]. I definitely suckered Al into that role, but he ultimately did quite a bit better than me in Hollywood with commercial features. He did Times Square [1980], though that film really made him suffer. I was still mostly living in Montreal when I was working in New York. I would make some money in New York and then do six months in Montreal.

SL: Is that what you were doing? You’d disappear for a little while and then come back?

FV: Yeah, I made good money in New York. But also, Bozo and I worked on a film called Country Music Montreal together.

SL: Unbelievable movie. I have such great memories of that movie.

FV: We got a grant for that. I don’t know why. I picked the subject, but we worked on it together. Maybe because I grew up in Florida around country music, and there was this country music scene in Montreal, which was such an anomaly. It was like one guy, and he would play in these bars with like six people, and he had cowboy boots on, kind of French country music, but in Montreal.

The Rubber Gun

Were you at all plugged into what was going on with other filmmakers in Montreal at the time? I saw a “thank you” to Roman Kroitor in the credits of The Rubber Gun.

FV: He was one, yeah. We weren’t that connected. We were connected with the Film Board. This woman, Susan Schouten, actually introduced me to John Grierson. I was trying to figure out how to raise money for the film and I hoped he was going to help me out. He kind of encouraged me. But we weren’t that connected with a lot of the older filmmakers.

Were you more oriented toward the gallery or the art scene at that point?

FV: We definitely were. I actually made a little bit of money doing photography, but not very much. I had a darkroom in the loft we had.

The loft that’s in Montreal Main? Where was that, Boulevard Saint-Laurent?

FV: Yeah. Well, it was actually on Rue Marie-Anne. Leonard Cohen lived across the street from Parc Marie-Anne [now Parc du Portugal]. The immigrants moved through the Main. The Jews had passed through as immigrants and were then the shop owners. The immigrants at the time were Greek and Portuguese. Cohen used to go to that place, with the Cookie’s Main Lunch sign—

SL: It’s now a bagel place.

FV: But they saved the sign. I don’t know if it’s just because it’s history or what. That area’s gentrified considerably.

And Cohen gets a brief namecheck in Montreal Main. Was there a sense of there being a real creative ferment in the city then?

SL: Yes. I mean, somebody referred to how shabby we made Montreal look, compared to how people think of it because of the Expo and this and that. I think we loved the immediacy, the texture of the place, and I think Leonard did, too. He was like the godfather of the street. A place like that, it’s like one of those movies in Brazil, or something, where people are shirtless half of the time and making it with a lot of sweat glistening on them. We don’t have the heat in Canada, but we have the shabbiness, and we have the love, we’ve got the romance.

I feel like the city would attract a more daring breed of outsider at that point, when a lot of the English speakers were moving out.

SL: ’71, ’72 was the FLQ thing [Front de libération du Québec, the terrorist Quebec separatist group]. The bombs. We were younger than the people leaving town. Those were people who had interests that they were worried about losing. We didn’t have anything to lose, so that made a big difference.

FV: There was more of an art ferment, an art group. We used to worship Montreal, our group, maybe 40 people who moved in the same circle. I think one thing that helped is that you could live on practically nothing. You didn’t need to get a job and make a lot of money. We had a support group—we were all kind of doing the same thing. We did a big show at a place called Véhicule in Montreal. Allan Moyle helped out, Stephen had some stuff in it.

SL: Unbelievable show. It was called Brother André’s Heart. It was named for the priest who built the second-largest church in the world, which is in the heart, well, not the heart of Montreal—

Montreal Main

I’ve been. The chapel full of crutches.

FV: Yes, St. Joseph’s Oratory.

SL: Supposedly his heart was there, and his heart was kidnapped, and held for ransom. This was ’74. We had released Montreal Main. Allan and I were working on the script in the magazine part of the Brother André’s Heart show. We had a beef heart wrapped in plastic in a baseball glove. We had a crucified Jesus, life-size, with a vibrator erection, and we had somebody on a step ladder giving the dildo a blowjob. A momentary performance. I did a heart that was made out of styrofoam peanuts. They were brand-new in those days, they were in the shape of worms, not the peanuts they later evolved to be. I filled a garbage bag with that and spray-painted enamel over it and tied it up so it had the four chambers, and covered it with those styrofoam worms, like the crown of thorns, you know?

FV: I put together the show and my contribution was huge black-feathered wings and a crow mask with a long beak, formally use in a performance of Leda and the Swan. I hung the wings and mask from the ceiling in an attack posture. Steven added the piece that really set it off, two leather motorcycle boots as the bird’s feet.

SL: You would have an opening, and there would be like five hundred people at the opening. So this was a community, and we were communicating to people.

Out of this scene, how did Montreal Main start to come together as a movie?

FV: Steve and I have differing opinions about this. For me, I wanted to make a movie, and I was trying to fish around for ideas for the story of this attraction to a beautiful boy. I wrote a script, and then we shot it on Portapak video. We were trying to use that to raise money, but we didn’t get any. And then I borrowed $2,000 from my Aunt Rose.

SL: So what’s my take?

FV: You tell me.

SL: My take is only about the idea. Your original script was about “Boy meets girl after college.”

FV: I don’t remember this.

SL: I do. And I said, “Yeah, that’s okay. I think I’ve read it before.” I said, “Look, you guys [Vitale and Moyle] sleep in the same bed.” It was gigantic, so they didn’t have to bump into each other. And they had this strange, great relationship. Back then I deconstructed every now and then, and I’d just run out of money. I left my apartment and moved in with Frankie, and he gave me the alcove. So I slept there, while the two of them had this giant bed in the middle of the loft, and we went about our own lives. And they were very much like boyfriend and girlfriend. They weren’t gay, but there was this element… And also everybody was so young, who gave a shit? I remember saying, “Why don’t you just have two guys together that live like this, and one guy broodingly has an affection for the other, and the other guy has an affection for himself being loved?” And then, one day, a pizza delivery boy comes, and he’s so beautiful that they both have a sexual idea about him. And I said, “So, they jump him, and it’s up to you to finish the script.” Then I left for California, and I was very sick at the time with mono, so that’s all I remember. And later Frankie sent me the script.

FV: It was originally supposed to be a movie with real actors, too, not us.

You mentioned a Portapak pre-shoot. Was that a scripted shoot or more in the line of improvisation to work the script out?

FV: No, it was scripted. I have all those videos, the scenes look so similar.

Montreal Main

The Portapak, at that point, was a pretty new piece of technology. How did you get your mitts on one of those?

FV: The Film Board gave it to me—I did a series of films called Hitchhiking, which are still shown at Vidéographe in Montreal. The guy who started Vidéographe, Robert Forget, was an engineer who put two Portapaks together to do switch editing. It was very primitive. You had to pre-roll it and all that stuff. But you’re right, it was early, but it wasn’t that expensive.

And the premise of the Hitchhiking shorts… You’d just hop into people’s cars?

SL: Frankie is an unbelievable voyeur. He turns what he’s looking at into an object that you could hold if your mind had a hand. The Hitchhiking movies, Country Music Montreal, Montreal Main, they all have a similar point of view of the person being… not at a distance, exactly, because there’s a complicity between all of us that are watching with him. That’s as close as I can come to articulating the quality. So it’s interesting that, what, 43 years after Montreal Main, and even though there isn’t a commercial drumbeat behind it, it still engenders the same reaction in people.

A word that came to mind while watching Montreal Main is “tactility.” Like, Frank, there’s the scene where you’re wandering through the Sutherland house going through objects in the bathroom, rummaging through drawers. You thrust the viewer right into the middle of the scene without establishing any kind of setup or orientation. As someone who’d spent a fair amount of time on other people’s movies, did you have a conscious sense of how different what you were doing was?

FV: I didn’t have a clue. I kind of rationalize what I was doing as I look back on it, but it’s interesting to see that scene with Bozo at the end saying, “I don’t know what I was doing.” Well, that’s exactly it.

The movie isn’t just a snapshot of some countercultural moment, it also manages to stand outside of that moment: we see some very unflattering things. Certainly with your character, Frank, and the morbid self-analysis that he engages in, and for the Bozo character, who we see performing these confrontational acts that might pass as transgressive, though it feels like he’s using that excuse as an outlet for plain nastiness. I think that’s remarkable, not only that you could represent this scene you’re a participant in but that you could be so pitiless in how you represent it and yourselves.

SL: Just the facts of life! There’s not that much disconnect.

Do you remember how local screenings of Montreal Main went? Was there any pushback?

FV: Well, we struggled through the making of the film. A company called Cinepix in Montreal gave me an editing room, except we had it only from 6 p.m. through 6 a.m. They locked us in the building so we wouldn’t steal all the equipment. They did a lot of exploitation stuff and were big players. So, we edited there, but we didn’t know what we had, not a clue. Then we got to the Film Board—we literally had to return Coke bottles to take the bus there—and showed them not a print, but an edited version, and people really liked it. That’s when we really turned a corner. The film screened for a couple of weeks at a theater in Montreal—I thought it was pretty cool that it was showing in an actual theater. We kind of got important after that.

SL: I think everybody goes through life with a fucking wind machine blowing their hair back, especially in the ’70s. The ’70s were superstar-land. I mean, look at the fashion! They were wearing platforms, and mutton chops, and gold chains around their necks! I mean, what the fuck was that about? You want to talk about people having inflated anything, I mean the collars were out to here—

There’s that great scene in The Rubber Gun where you go off on a fantasy kick, become Conan the Barbarian for a moment.

SL: Right. “Call me a Kushite”? But did we become big shots in that scene, in the art scene? Absolutely not! We weren’t making any money. We weren’t working for money, we never made any. And you wanted to make money. East End Hustle…

FV: Yeah, I did.

Is East End Hustle a movie you’re happy with?

FV: No, I hate it.

SL: You should hate it. This fuckin’ guy…

East End Hustle

But you’ve got a writing credit on it!

SL: Yeah, but he didn’t listen!

FV: I mean, you probably did give me some good guidance, like “What the fuck is this about?” It was about sex and action… But here’s the thing: I had made Montreal Main and didn’t make any money. I thought, well, you have to make money, a film has to make money

East End Hustle definitely feels like you’re trying to channel some of the same energy into a genre framework.

FV: Exactly. And I did another film in New York after that called Thunder Born [1989], which has [producer] Joseph E. Levine’s money’s in it.

SL: I never saw that one.

FV: It was never released…

SL: Any good?

FV: No. Joseph’s son [Richard P. Levine] borrowed a lot of money to make the film, and then couldn’t pay it back. The bank said, “Well, unless you pay us back all the money we can’t release the film.” But my point is that I thought I’d made this thing, Montreal Main, that was a failure because it wasn’t going to make any money, but then it turns out to be the best thing that I’d ever made. So that’s kind of sad.

I’m not quite sure what it means, but someone said, “Oh, that’s a docu-fiction film.” It’s listed under the docu-fiction category on Wikipedia. And I just finished another one called Anorgasmia, about a woman who gets no pleasure from sex, that I’ve been trying to get into festivals. They are all letting me submit it for free because of Montreal Main, but none have accepted it so far.

Stephen, you had mentioned in the Q&A at Anthology that the idea had been that Frank was going to do his movie, that Allan Moyle was going to get his chance to direct—

SL: And then I would.

This was something you guys had worked out?

SL: I thought there was a kind of handshake thing. It didn’t matter, I never followed through.

FV: Maybe we talked about it.

SL: That was in my mind, but Allan and Frank weren’t as close by then… they had reached capacity. The cum was starting to come out of the mouth of the corpse. “This one’s full, send up another!” Remember that joke? You do, Frank, I can see by the veins popping out of your head! [Laughs]

But you were at least close enough that he could pull you back into the fold to shoot The Rubber Gun. What was the genesis of that film?

SL: I’m going to say the wrong things. Allan’s one day going to say to someone, “He’s a prick, what did he say?”

FV: He’d never say that. I know him.

SL: I’ve always thought of myself as the toad, maybe getting lucky underneath the log as things fall off. But Moyle liked what I did, and he said, “We’re going to do this, so write a scene, here we go.” And he contrived the whole drug deal thing and made me fill in the blanks. So I did, but then in the end I was kind of tired of the whole issue, and I just wanted to be painting and stop with the filmmaking.

And that’s something that’s in the film, this feeling of being fed up with the scene, the line about, “Yeah, everyone’s just getting high to make themselves feel five years younger.”

SL: Woodstock was over! Get over it everybody. We’ve got to get up and do it. In some ways, that’s the portal to the ’80s, because the ’80s came, and everybody that didn’t make money in the ’70s, and had a good time in the ’60s and got laid in the ’70s, then became greedy in the ’80s, and you have all the things that culminated in the ’87 when the stock market crashed, and your Gordon Gekkos and all of that—who by the way, that person is a collector of my paintings. So it all comes together. The guy that that character is based on is an art collector. He has a couple great pieces of mine.

The Rubber Gun

Frank, had you sort of hit a wall in Montreal after East End Hustle and The Rubber Gun? Did you stick around town?

FV: I made my best production. I got married and had a son in 1980. But I guess I hit a wall, and I wanted to, for whatever reason, come back to New York.

You do feel this sense of letting go, watching these movies in proximity.

SL: A stage of development. You’re watching the caterpillar struggle out of a cocoon. Everybody’s envious of the cocoon because it’s made out of silk, but you’ve got to expose the raw caterpillar to the air, harden the shell, crawl up the tree, start munching more leaves, and do the thing. You’ve pupated.

I wonder how much of that was self-consciously there in the making, and how much is something you only see looking back?

FV: I don’t think it was self-consciously in the making.

SL: No. I think we knew, though, that we were losing our childhood, that reality was coming in and changing everything and that it couldn’t go on for two reasons. Economically, it was unfeasible. It’s one thing to be able to sleep in a pile of rags and shabby clothes and eat bad food and have multiple lovers, but that gets tiring after a while, and you have vulnerable moments when you need real, sincere support from people who are committed to your well-being. There’s a moment in On the Road where Kerouac gets sick and Neal checks in on him, and then leaves town, leaves him in Mexico or something like that, sick as a dog. That’s a tough thing to deal with, to be sick by yourself. I think maybe Frank’s disappointment with East End Hustle led to his subsequent marriage and breeding. Allan once said to me, “You’re like every other failed artist. You couldn’t make it in the creative world, so you had to have a child.”

FV: He said that to you?

SL: Yeah.

FV: He said that to me. And I thought about it, and I thought about it, and I said to him, a while later, after I had had a year’s worth of being a parent—the wonders, the beauty of it, the fantasticness—as only I could: “Allan, I want to ask you a question. When you’re in Bloomingdale’s and you’re in the basement shopping for discounted sweaters from Armani, and you look over and there’s Warren Beatty also saving a couple of bucks, I want to ask you—of all the fabulous people that you aspired to know and do know, how many of them in the last 12 months have grown six inches, and not in your mouth?” So, that’s the wonder of being a parent. All of a sudden, you give up your own “Where’s my place?” and you wonder where their place is, which eventually helps you find your place.

Among other things, Montreal Main is an incredible time capsule of the city. For example, you’ve got a knock-down, drag-out scene in Schwartz’s deli, which looks like a working-man’s eatery in the mid-’70s.

FV: We had no money, I’m surprised they let us do it. The real trip was a place called Lachute, a little town outside of Montreal, it’s known for the flea market and the auction. It’s kind of cool that when you’re young like that, and you have these images of places in your mind, and you just go and ask them and get permission. Then there’s Frites Dorées, it was just torn down recently, but that whole area was a bunch of hot dog stands.

And the penny arcades, too.

FV: We used to go, after a night of drinking or whatever, to get a 10-cent hot dog.

SL: They were delicious! You know what our friend Abe used to say about them? He’d say, “Lack, let’s go down to the Main and have a steamer.” I’d say, “Fuck, Abe. I don’t want to eat that now. It’s two in the morning.” He’d say, “Lack! They’re good for you!” I said, “How can you call that boiled fat good for you?” He says, “Hey, they keep you alive, the rubbies live on them! Have you ever seen a young rubbie?”

Montreal Main

As a non-Canadian, what the hell is a rubbie?

SL: A rubbie is somebody who drinks rubbing alcohol.

FV: You know that scene where I leave Johnny behind at the corner store? That area just means so much to me. It’s a lot of ramshackle wooden buildings. Some of them are two stories high. The streets aren’t squared off, they kind of come in at an angle. It was like going back in time.

SL: It’s Chateaubriand, the east end, east of—Saint-Laurent is here, then you go east…

FV: I’d call it Montreal East or Saint-Denis. East of the Main was French. West was more English. It’s just another world. Even where Leonard Cohen lived, that street along there. I mean, I don’t know what it’s like now, but there were all these happy drunks leaning against each other…

Frank, you edited Montreal Main as well. It has a really interesting staccato editing rhythm.

FV: You know, it does, and I think that what I like about it is that it’s not linear in many ways. Sometimes you just jump off from one thing to the other, but they connect, they make sense.

There’s a lot of crosscutting, for example, when John and his father are getting into it in the car, you go between that and another argument. To your recollection, was it written like that, or was that something you discovered in the editing?

FV: I was surprised by how much of it was already there in the video pre-shoots when I saw them again. Again, I think the term docu-fiction fits. I’ve realized that’s what I want to do. In a way, it took me 40 years to find this kind of thing. Those two big 35mm fiction films, with a huge crew and a huge cast, just didn’t cut it. I think this is where I’m at. I like this stuff, using real people. But I like fiction, I don’t want to do straight documentary.

SL: I never made the third film, or whatever we were going to do, because we all left town and became our own movies. And now that I’ve been working at it for 40 years, I look back and say, “Well, what the fuck have I been doing?” But, recently, a friend of mine, Philip Pocock, who’s a media and communications professor in Germany, said, “Stephen, you have done the longest film, frame by frame.” Because I have about maybe 3,000 images that would be of exhibition quality. And it’s a film. So it’s the same thing that Frankie says: I don’t want to deal with a crew of 35 people and budgetary considerations. I just want to be alone and do it. But I take in media, and images from the outside world, and then, like a spider, inject my fluid into it and digest it. It’s got to be dead before I can digest it, so media kills it. And then I bring it back to life, I reconstruct it. So that’s what I’ve been doing. That’s just how it’s all evolved from this departure point of us all wanting to communicate and, at the same time, having a little bit of narcissism to think that we’re worthy of watching.

Nick Pinkerton is a regular contributor to Film Comment and a member of the New York Film Critics Circle.