Interview: Errol Morris (Part One)

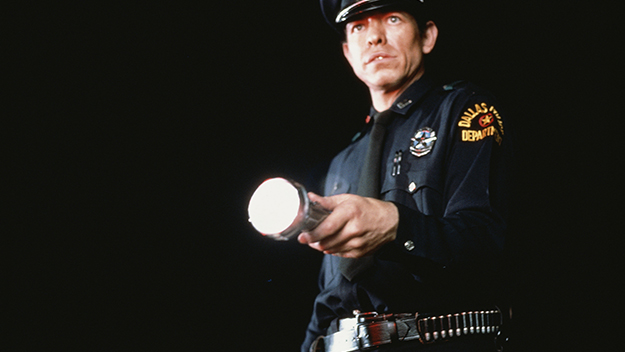

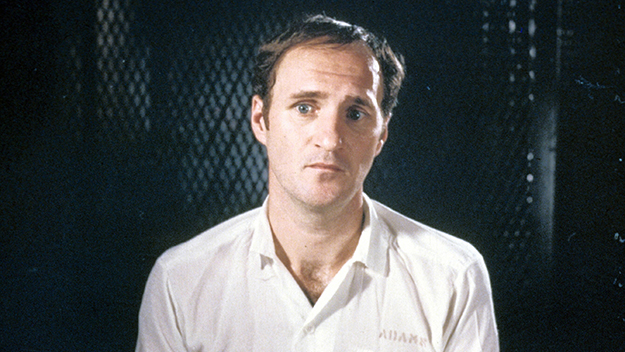

Over the years, Errol Morris has explored a number of forms, chiefly feature-length films, but also shorter works, book-length studies, New York Times articles, ads, and, one might say, the interview itself. Wormwood is a four-hour, six-part series that will stream on Netflix starting December 15 and, in a just-announced “non-episodic” form with an intermission, will screen theatrically in qualification for Academy Award consideration at the same time. It’s the spiraling story of Eric Olson and his father, Frank Olson, a military scientist who died from a mysterious fall out of a Manhattan hotel window in 1953. A kind of postwar nightmare from which Eric can’t wake up, Wormwood shows the son (who pioneered a form of therapy involving collages) boring deeper into the truth of the matter, amid endless cover stories and distractions from the U.S. government, across decades. And that Academy Award consideration will be in multiple categories, because Wormwood consists not only of Morris’s sit-down interviews with Eric Olson, but also reenactments and dramatizations, starring Peter Sarsgaard as Frank Olson, as well as Bob Balaban, Christian Camargo, and Tim Blake Nelson.

Wormwood, in six-part form, had its international premiere in September at the Venice International Film Festival. There, journeying by boat from the Lido where films are screened for the press, to a separate stand-alone island, I met Morris for a lengthy chat over coffee about his newest work. Netflix’s generated keywords for Wormwood aren’t wrong—“Provocative, Cerebral, Ominous”—and our conversation moved freely among the non-obviousness of the truth, 10-camera setups, Eric Olson’s maddening predicament, the sense of an ending, and the dark prospect of a government that can kill its own citizens (which recalled for me an interview, years ago in different circumstances, in which Morris spoke to Rob Nelson of the “scary” prospect of “a rogue government—a government whose officials believe they’re entitled to do anything”). Part one of the interview is below.

Wormwood

How is episodic documentary different for you from making a feature-length movie, in its shape and in what the length allows?

Well, it is different. I was wondering if this is some kind of test question to see if I know the difference between a feature-length film and a film that’s actually five hours in length.

I was wondering what opportunities it allowed you, the longer format, the episodic format, the kind of ability to double back, for example.

There’s one obvious opportunity—it’s longer. But it’s really incredibly different. First of all, it’s episodic, so you have, in some sense, six separate films which are joined together. There’s that ongoing issue of, how do you keep people interested, the necessity of constructing cliffhangers at the end of each episode to keep people coming back for more. And it allowed me to play all kinds of different games than I would have been able to play in something that was a straight feature. Maybe not impossible but certainly more difficult.

What do you mean by games?

I was interviewed by Jonathan Lethem for Telluride, and I was asking him: is genre-bending like spoon-bending?

Yuri Geller or whatever.

There you go. But it is genre-bending, and intentionally so. There’s the what-do-you-call-it problem, hyphenated. I sold it to Netflix [a waiter asks Morris if he’s okay for coffee]—oh, I’m so okay, thanks.

That’s very relaxing to hear.

It’s strange here.

Especially the courtyard out there. Have you ever seen that Italian science fiction movie from the ’70s? Morel’s Invention. Two people wash up on an island and they realize there are holograms of people going through the motions there.

It has a little bit of The Prisoner [here]… So, you have these diverse genres. I sold it to them as the Everything Bagel. Drama, reenactment, archival, interview, a little bit of everything.

Morel’s Invention

And you’re in it too.

And I’m in it too. And Errol Morris.

A genre unto himself. But that was noteworthy, to me, because we don’t often see you in the frame in your films. That seems like something a little different—to include yourself in it.

It’s hard to exclude yourself from it. I mean, I could. The Interrotron, you’re automatically excluded from it. Just because of how it’s set up. You could be put in it, but you’d see pieces of the Interrotron, it wouldn’t just be me sitting in an interview situation. And the Interrotron, I have tried in the past to include myself in some way but it doesn’t quite work.

How so?

There are two cameras of course: it’s recording the image of the person that I’m talking to and it’s also recording me talking to that person. But those two don’t cut together.

Have you ever put an interviewee behind the Interrotron and then you’re in front of it? I guess that doesn’t make sense.

It does make sense. It’s the same thing, I mean, it’s a mirror image. I recently did a set of commercials for a company called Wealthsimple, and I interviewed my son [Hamilton Morris] who has a TV show on Vice. And Hamilton interviewed me. We turned it around in the sense that I stood where he was standing and he stood where I was standing.

You swapped.

We flopped positions. But this [Wormwood] had 10 cameras. You can see that there are a lot of shots.

You’re definitely changing angles a lot, but I didn’t realize there were that many cameras.

Well, the Interrotron, I only use the two cameras, or maybe a third camera that is taking a shot just off to the side.

With Tabloid you were sometimes jumping around a bit.

Tabloid was done primarily with three cameras, I believe.

With 10 cameras, what was the idea behind that? To fragment things more?

I think the idea was to have 10 cameras. In a way it’s easier to cut with 10 cameras. But the underlying metaphor about collage and collage theory and investigation being an assemblage of diverse elements pieced together, it seemed like a visual metaphor that works, that has some meaning in the context of the film.

It is interesting to me that you include yourself in those interview shots, because you are an investigator as well. So you had two investigators in the same room. I took Eric Olson to be an investigator of his own life.

Yes.

So it becomes this self-portrait.

Intentionally so. It is kind of like an Interrotron shot, it’s different really, but it’s like an Interrotron shot. So among the 10 cameras I would have one camera, long lens, and it’s behind me, focused on, say, you, and I’m soft. You can see the side of my head or my shoulder. And it’s close to an Interrotron shot. Of course it isn’t. An Interrotron shot is produced in a completely different way. But it gives you this range of shots.

Wormwood

I was also curious how you shot the reenactments, with the actors. The affect of the reenactments is very interesting to me, because it’s a drama…

I would distinguish between drama and reenactment.

So these are dramatic scenes?

I would say there are both: there are reenactments and there are dramatic scenes which are really not reenactments at all.

What would be an example of each? Or are they all a little of both?

No, I’m trying to make a distinction.

I got it exactly wrong.

Not exactly wrong. But wrong. When you see Peter Sarsgaard come into the house and his wife is cooking, and he goes into the bedroom, she follows him. And he throws his hat on the bed, she takes his hat off the bed.

Bad luck.

Supposedly bad luck. Goes into the bathroom, she makes a phone call. What exactly is that reenacting? You tell me.

So that’s a dramatic scene.

I actually think people don’t know how to talk about this film. I don’t even know if there’s a right way. And I can see that there’s this problem. I’ve tried throughout my career, for better or for worse, maybe for worse, to do things differently. Gates of Heaven was a contrarian movie, to be sure. I was aware of all these documentary rules I was supposed to follow and I systematically broke all of them. And I got into trouble with the reenactments in The Thin Blue Line. And this is different, this is not the The Thin Blue Line. Because you’re stepping out of a documentary world altogether. If I’d had my way, had my druthers—whatever druthers are—there would have been even more drama. It’s expensive, particularly period drama where you’re re-creating the 1950s.

The Thin Blue Line

And you have to build sets for all of that…

Of course. And I would like to do not exactly this again, but I would like to do it again. I think there’s something really interesting to be uncovered this way. It intrigues me. At first I didn’t even know whether it would work, whether you could create this blend of so many diverse genres in telling a story. And I believe it does work—you have to tell me.

I believe it does, and by the end, it’s deeply unnerving. Actually, I do have a big idea about the movie.

Uh oh.

Which perhaps I should say.

Please.

My big idea about the movie is that it’s about the problem of endings. Whether that’s in reflecting on life or in creating a fiction or a documentary or a piece of art. When do you end, when is it complete, when is it over?

At the risk of being too accommodating, I would agree. First there’s the question of detective work and endings. And we all have an idea of what that means. There’s a dramatic structure to a detective story, or at least there used to be. There’s a dramatic structure to even real detective stories. I was a Wall Street detective for many years. And we think of the detective story as coming to a conclusion: what actually transpired, what happened, is the defendant guilty or innocent, and on and on and on and on. The classic example is Poe’s Murders in the Rue Morgue. You’re presented with this pile of evidence that doesn’t quite make sense, and you and the detective puzzle through it trying to figure out what actually transpired. And it is tied up in a bow at the end. The orangutan did it.

If only that became the convention rather than the butler. In the history of the detective novel.

Yeah, it was the orangutan, Goddammit!

Who would have suspected?

And then all of a sudden these clues, these disparate pieces of evidence cohere. They form a picture of reality, of what must have transpired and what must have happened. But then, there are other kinds of detective stories where you don’t come to any kind of tidy conclusion. And I was lucky. So I made this film, The Thin Blue Line, and I really did investigate this case. I made a movie about it, but the more interesting is the actual detective work, some of which you see on film, most of which you don’t. And it’s kind of amazing, I’m still amazed by it. Because you have two separate investigations at the same time.

You have the investigation of Randall Dale Adams. Did he do it? What evidence is hopelessly incriminating? Or, on the other hand, what evidence suggests that he didn’t do it? And then you have another guy, this 16-year-old kid, and it’s the same deal. What evidence shows that he did do it? What evidence shows he didn’t do it? And as I investigated, all the arrows start pointing in the same direction. They start pointing to David Harris as the killer and to Randall Dale Adams as the innocent victim of a terrible miscarriage of justice. It’s what a detective dreams of happening. Another piece of evidence comes in, it further establishes Adams’ innocence and Harris’ guilt.

What happens when you don’t have that tidy a story? So I wrote a book about a case that has vexed me for years, the Jeffrey MacDonald case, a book called A Wilderness of Error. And I used a quote from Edgar Allan Poe from his doppelgänger story “William Wilson,” and it’s one of my favorite quotes: seeking an “oasis of fatality amid a wilderness of error.” And the way I always imagine it is finding certainty in a sea of disparate, confusing facts and scraps of evidence. I believe in truth, I believe in a real world. But are we always able to establish what’s true and false? Is it a fact of the matter that the CIA or people working for the CIA tossed Frank Olson out a window at the Statler Hotel in 1953, or did he commit suicide, or did they create a situation where he was compelled to commit suicide? Saracco, the New York detective, talks about just such a possibility. They commit a murder that looks like a suicide.

And then the fact that it’s in the manual—

Right, the assassination manual. Every home should have one.

The Thin Blue Line

Like the Bible in every motel room. It’s strange when the truth of the matter intersects the lurid fictional paranoid fantasy of the matter—the government teaching people how to kill in these ways. And then you find a manual that is actually that. That was another level of the drama for me: having suspicions confirmed or having paranoia confirmed.

I don’t always like my films, but I kind of do like this one because it expresses a lot of things that interest me. I assume you’re referring to Sy Hersh’s speech in Part 6 where he says everybody loves endings, but maybe you can’t tie a bow around it.

That’s the thing: when do you stop? When are you satisfied with the story? When does it have a sense of completion for you? You reach a kind of endpoint with your interview with Sy Hersh, when he talks about a source who can confirm the existence of certain information but cannot be identified. That’s as close to the known unknown or whatever you might call it as we get.

It can’t be in some way publicized.

Though the one thing I didn’t understand is that he makes a comment about someone signing in to see government records. Couldn’t they figure this out—I don’t know…

No, go on, I’m interested.

They could just check how many people sign out whatever document that guy looked at of who was killed in 1953. Probably the last person to look it up would be the person who talked to Sy Hersh. You know what I mean?

I know exactly what you mean. I don’t want to claim to be friends with Sy Hersh but I talk to him often enough now and I find Sy Hersh endlessly interesting. Sy said something to me that I really believe, and he says it in the film, that he didn’t want to turn someone into a Snowden. And what does he mean by that? To Sy, a source is something that you protect, you protect at all costs. And why? There is an element of self-interest as well. The source is giving you information, potentially could continue to give you information. By outing the source, you destroy the possibility of getting something more, of learning something in the future. So you don’t do that. Snowden, for him, is an example of what you don’t do. You keep Snowden in place, you keep learning more and more things from Snowden. You don’t end it, you continue it. And as an investigative reporter, that makes complete sense to me. Also if a source gives you information, not necessarily but in all likelihood, that source is giving you information illegally, they’re giving you information for which they can be punished.

There does seem to be an inability for humans to keep secrets forever. Or to put it another way, there’s a compulsion to talk.

It’s my version of Shakespeare: the best part of discretion is indiscretion.

Not valor, right. That’s another thing that the series keeps making one think about: how people hold onto their secrets so long, and why they wouldn’t or couldn’t talk earlier.

Spill the beans. At least a dramatic deathbed confession.

Maybe some of them are waiting for that kind of special ending. But it’s interesting how there’s almost a cultural hold on them—a government culture of secrecy that they lived and worked with so many decades.

There’s another phenomenon that fascinates me. The best example I can give of this is the first time I met Randall Adams in prison, Eastern Unit in Texas, and I’d scheduled six or seven interviews that day. Prisoner auditions, please dress informally. Adams tells me this cockamamie story about the kid, the police officer, blah blah blah. Did I believe him? No, of course I didn’t! Did disbelieve him? No, I didn’t know enough about the story to think one thing or the other. I listened. I subsequently heard that interview many times and what’s interesting to me about it, and I remember it pretty well, is it’s the feeling of someone who has told a story many, many, many, many times and no one has believed him. I often have asked myself how long would it take the Dallas Police to convince me I had committed a murder I didn’t commit. I give myself 15 minutes. Maybe a little longer. But what happens when you tell a story again and again and again and again, and no one believes you? He had this sing-song quality, like he might not even believe it himself. Like he was repeating something that someone else had said, a kind of strange mantra.

We always think that reality is obvious. Reality is the most inobvious thing in the world. And I got so defensive after The Thin Blue Line. “How dare you use reenactments.” I have a book coming up, by the way, University of Chicago Press, at the end of the year, called The Ashtray. The subtitle is The Man Who Denied Reality. But it is really about how we have knowledge of the world, or even more significantly, how we deny knowledge of the world.

It’s hard when you’re in the position that Eric Olson is in, because he’s repeatedly told a certain version of his father’s story, and then some time passes and he learns that version—

Someone pulls the rug out.

[Tune in next week for part two of our interview with Errol Morris.]