Interview: Danny Glover

It’s a pattern familiar to any observer of the movie business: a filmmaker does a big-budget Hollywood movie for the money, then does a smaller-budget project for the passion and prestige; rinse and repeat. Yet Danny Glover’s work as a producer feels tangibly different, largely because it demonstrates a commitment to a certain ideology that challenges the status quo of Western art, goes beyond simply showcasing his own talent, and extends far outside U.S. borders.

A longtime champion of foreign and art-house cinema, Glover first assumed the role of executive producer with Charles Burnett’s To Sleep with Anger (90), a uniquely haunting magical realist story of a black family in South Central Los Angeles, in which he also starred. Glover went on to co-found Louverture Films (named after the leader of the Haitian Revolution, Toussaint L’Ouverture) with Joslyn Barnes. The production company has since helped produce Abderrahmane Sissako’s Bamako (06), Carl Deal and Tia Lessin’s Trouble the Water (08), Elia Suleiman’s The Time That Remains (09), Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s Palme D’Or winner Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives (10) and Cemetery of Splendour, Göran Hugo Olsson’s The Black Power Mixtape 1967-1975 (11) and Concerning Violence (14), and Lucrecia Martel’s upcoming Zama.

A conversation with Glover, 69, is not just a lesson in how to be a successful producer, but in history and art. FILM COMMENT’s Violet Lucca interviewed him shortly after the New York African Film Festival at the Film Society of Lincoln Center, which screened Tala Hadid’s Louverture-backed debut 2014 feature The Narrow Frame of Midnight, a story centered on a Moroccan-Iraqi writer’s search for his brother. Next week, the Sony Pictures restoration of Charles Burnett’s To Sleep with Anger will have its world premiere at the 72nd Venice Film Festival on September 8 and 9, just in time for its 25th anniversary.

To Sleep with Anger

The first film that you produced, To Sleep with Anger, was made in a very different environment from today’s independent film industry. Could you talk about your experience getting involved with the project?

I knew Charles Burnett from Killer of Sheep, and To Sleep with Anger’s script came to me in early 1988. When I first read a terrific script, sometimes the story will conjure up images in my mind, a story that was probably already in my subconscious. I’ve spent a lot of time with my grandparents and the myths that go around in rural black life, so that was somewhat a part of my life. My grandparents were rural farmers born in the last part of the 19th century. When I read that script, it was an opportunity to delve into stuff that was really a part of my subconscious memory.

I had done the first Lethal Weapon [87], and because they anticipated that there was going to be a second one because of how well the first one did, Sony gave us $4 million. Underline that: $4 million! Now they try to get you to do a film for a million. That’s how things have changed. Sony gave us $4 million to do a film that is still considered one of the greatest independent films in American cinema. With The Saint of Fort Washington [93], we got money from the U.K.—$3.5 million—and Warner Brothers, in their desire to please me at that particular point in time, put up the other $3.5 million as part of the deal to do a Lethal Weapon 3. I was able to use my leverage, which is nothing new—a lot of actors do the same thing. And Warner Brothers got what they wanted too.

When you talk about To Sleep with Anger or The Saint of Fort Washington, they fall somewhat within the parameters of storytelling in American cinema. But I’ve always had an idea of looking at films beyond just that narrow precept. I started watching foreign films when I was about 17, when there was Ingmar Bergman, the great Akira Kurosawa. And then what really opened up the whole world of possibilities was when I started looking at the films of African directors, particularly out of West Africa: Ousmane Sembène, who became a very good friend; Djibril Diop Mambéty, out of Senegal, with his film Touki Bouki; Souleymane Cissé, whose film Brightness is one of my all-time favorites. They were stories really about the adjustment to the process of decolonization: what does it look like? What do we look like? Who are we within that process, or after that process has happened? There are a whole slew of directors that touched me, moved me. Satyajit Ray, the great Indian filmmaker. Iranian filmmakers and others in the Middle East, Youssef Chahine from Egypt, Korean films, all those are within my framework. Films from Argentina and Brazil became a part of my vocabulary. Also, the great filmmakers of Europe: Godard, Fellini, Tati, Lina Wertmüller—all those films she did that I love. I could go on and on and on with all the things that we saw.

Then somebody figured out that if you make a $100 million film and put $20 million in it for P&A, then you could put up ads to take up all this space, and from that you can predetermine what you’re going to make off the film. Instead of seeing the democratization of filmmaking, you saw the narrowing of it, which is what we have today.

Bamako

I’m interested to hear about your experience producing films in places outside of the U.S., like Africa or Thailand, because there are so many co-productions, and with governments that have robust—or just existent—arts funding, unlike the U.S.

There’s a huge difference. With Bamako, we put in a considerable amount of money because there were monies from the French government; other money went into the film as well. Joslyn—and let me underline the name Joslyn Barnes and say it 15 times—has been really the engine behind Louverture Films. She’s been the one who’s found money in Doha for Tala’s film, and investors here for Tala’s film and for Apichatpong’s films. Even though we put money in, she was finding money and getting other people. It’s a generous group of investors who played a part in this too, and in small amounts. The thing is that you’re not bridging all the other kinds of particularities that you deal with when you make a film in the U.S. Sometimes we put in money because you understand it to be a tax write-off as opposed to being equity, or an equity-player. There’s another culture about doing film in other places in the world, a culture that’s not present in the United States.

I’m also talking about the storytelling. Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives… [Laughs] I just love saying that title. I’m talking about memory, psychic memory. When I talk about my parents, my grandparents—my mother’s greatest gift to me was her family. I’m hanging out with the only first-cousin that my mother has alive, Fanny, and there’s something absolutely remarkable about that. There’s the repository for all of that memory that goes back way beyond me. They actually knew my great-grandmother, because Fanny’s father was my grandfather’s brother. Fanny’s grandmother was born in 1853, 10 years before the Emancipation Proclamation. She has a whole collection of memories that come out in her own behavior and her own patterns of speech, her own way of putting together—it’s amazing. She was also very close to my grandmother. And their worldview—or how they interpret the world, or how they manufacture their lives in the world—is a part of me in a sense.

So when I see Uncle Boonmee, I think about all the kind of stories I’ve heard about the little farmhouse in the middle of the night, where it’s totally dark, there’s no moon and you can’t see. All those become a part of how I’m able to adjust to the world or see the world. And when Apichatpong’s film came through, it knocked me out! Because I have a context.

Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives

We’re in an era when it’s never been easier to ask for funding with Kickstarter or other crowdfunding services, but it’s also harder to get people to pay attention to films. Is it more difficult to find funding for upcoming filmmakers like Tala versus someone who’s more established?

It’s a challenge in both instances. If you take Apichatpong’s most recent films: all of them have been at Cannes, and Uncle Boonmee won the Palme d’Or, but we had a rough time finding money for Cemetery of Splendour. To some extent, it’s not who the filmmaker is, but how they’re going to do at the box office, how much money you’re going to make, who you have attached to it. All those things play a role in what kind of ideas get realized, whether you’re a new filmmaker or established filmmaker. For Tala’s film, we went to places in the region where the film takes place, and we were able to get money from areas that are normally off the radar, where certain films can’t go to because they’re American. A great deal of that money is soft money, grant money, money that was provided with no expected recuperation on the investment, which makes a huge difference. A lot of Bamako’s financing was soft money, too. I think the fact that Tala’s a woman is another reason that we have a little easier time now, so we’re not going to push anything. We’re going to try to make money at the box office. Whether we’ll get a return on the investment is a whole ’nother question.

When we talk about difficulty in making a film and raising money and everything, it’s just the institutional ways of raising money—and this is my own kind of hurt feelings and thinking—just about everywhere is challenging. Whatever you’re doing is challenging. I’ll give you an example. There’s going to be more money available now than perhaps a decade ago, or even two years ago, for organizations that are dealing with the issues around incarceration, police brutality, resentencing, and all the issues around that, because of what has been happening. It’s on the radar screen not only of this country, but the world. The money is going to be subject to the visibility of the particular issue itself. And so places where we were able to get the money from, for these foreign films, are places where agencies, the government, or whatever, feel that it’s necessary that film be used as a reflection or a tool to tell a specific story.

American film doesn’t function that way. However, in the past, because the political dynamics of the moment itself suggested that it [reflect certain events], it did. The reimagining of African Americans within American society at large during the civil rights movement made it evident: film was a way of giving a texture to that. Historically, Sidney Poitier represented a different character than Canada Lee. So all film became an adjunct to establish his place not as a forerunner of what was happening, but as something that was able to ride the wind of what was happening. If you see an abundance of African Americans on television now, it’s because of several things. Or you see that certain kinds of films are being done. But the most serious stuff comes on television now rather than in the theatrical releases.

Selma

Given this changing climate and the critical success of a film like Selma, are you more optimistic about getting your film about Toussaint L’Ouverture made?

Well, they’re apples and oranges. What Selma does—that’s a film on Martin Luther King in 1964. The idea of Selma exists within the accepted framework, the accepted context. I mean, it’s sad that we’re still talking about voting rights. Remember, Selma came out roughly around the 50th anniversary of the Voting Rights Act, and there was this whole campaign… Now if there were a film about King at Riverside Church on April 4, 1967 to him in Memphis on April 4, 1968, then I’d see something more, something different. We’re talking about a King that’s up against major oppression, pressured from all over, because he’s been denounced by every major newspaper, every major organization, for his views on Vietnam. The New York Times called him an agent of Hanoi. You could go on and on and on. People began to distance themselves from him.

We’re talking about two different Kings. For those people who were involved in Selma that summer—and there’s a lot of them alive, a lot of them still doing work—they’ve said that the film may not ring true to what really happened. [Laughs] So, what are you saying? Did it push the discussion about voting rights further? Now, say you do a film about King, from April 4, 1967 to April 4, 1968. We all know that he was assassinated in 1968. But you could see what was happening during The Poor People’s March in 1967, which is a different film. We need poor people marching now. When King denounced the war in Vietnam, he set himself on another trajectory, part of his evolution, anyway. The Freedom Party, who were trying to unseat the [all-white] Mississippi Democrat delegates, came out against the war in Vietnam three years before King did.

What else are you going to say about the civil rights movement? You’re never going to do a film that’s going to morph or suggest that the movement became more radicalized by those young people who were part of SNCC [Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee]—Stokely Carmichael and James Forman, who is depicted slightly in the film. Malcolm X is depicted slightly in the film, and he was assassinated in 1965. The film itself is not an event, but it gives us an insight to where we are now, in relationship to what has happened in the past. It’s different from most filmmaking in the United States in that respect. But notice that the first moment we see King in the film is 1964, when he’s receiving the Nobel Peace Prize. It doesn’t show his acceptance speech, which shows how he’s thinking about how to relate to the rest of the world, where he’s moved past “I Have a Dream.” Then we have the murder of the girls in 1963. All these things are tied together in some sort of tableau, without any kind of historical context. But it doesn’t give us a real sense of where King was at that time.

Selma is an acceptable narrative within the framework of American film. Now, the film Toussaint is another narrative. Edward Baptist’s book on this came out last year, The Half Has Never Been Told, about how slavery built American capitalism. He has a small section in his second chapter where he refers to New Orleans and the Louisiana Purchase, and in that section he talks about the importance of the Haitian Revolution in relation to the U.S. acquiring all the territory to Oregon and Washington, which was French territory. You never see that in American history books, because that means that Africans, or black people, have something important to say in the building of this country. What’s indisputable and terrible too is the fact that slavery, the expanse of slavery, had played a major part in building the system here and the power within this country. It was not simply the South. It’s complicity from the outset—the establishment of the nation, the establishment of the Americas—the complicity between the North and the South in that action.

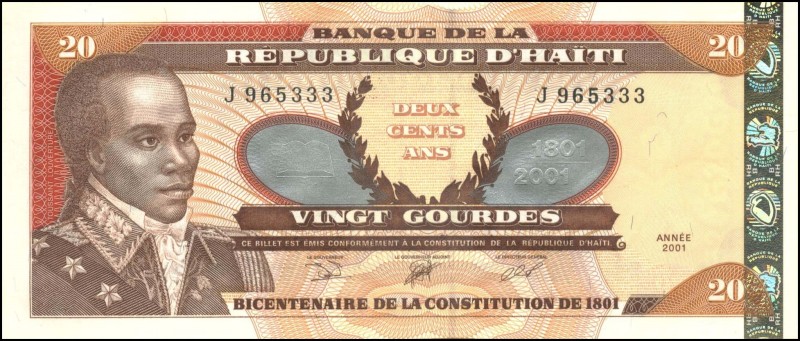

Toussaint L’Ouverture on Haiti’s 20-gourde note

Those are the stories that you’re not going to be told in American film. Those are the stories that are not going to be seen. Because what you have in the Haitian Revolution is the defeat of an empire. It’s the first and only time where slaves threw out the power enslaving them and formed their own country. The first time. It’s not an acceptable narrative in American film.

Yes, I would agree.

So we have 20 Selmas being done, it doesn’t make any—it’s an acceptable narrative. What we need to do is look at that, and understand that right now. Because filmmaking relies on our historical understanding of ourselves, and gives us some clarity and understanding about who we are and where we come from. But if we told the real history of what America is, the American people would be schizophrenic. We’d be crazy. This is what we really are? This is what really happened to Native Americans? This is what really happened to slaves? We were kidnapped and everything else? And we can’t even apologize to all the descendants of all the slaves, anywhere, for the politics of slavery.

Yet with everyone from Michelle Alexander to Douglas Blackmon, who wrote the book Slavery by Another Name, about U.S. history after the Civil War to the early Forties in the South, and the mass incarcerations and re-enslavement of African American men and women now—if you take the history from The Half Has Never Been Told, and connect that Slavery by Another Name, then we have a whole different theory of American history from 1783 to just before World War II. That’s not even taking into consideration the seizure and theft by treaty or by whatever of Native Americans land, or the annexation of the Philippines, Puerto Rico, and Cuba, and the Spanish-American War. This doesn’t even include that. We could take this right up to World War II just in terms of the black people in this country. And then 12 years after that, we’ve got Brown v. the Board of Education. So those are the kind of films that are never on our radar. It’s never told in the framework of a narrative, or as a series of narratives.

The people who supported the Toussaint film, are people like Hugo Chavez. Because he says: “We in Latin America owe so much to the Haitian Revolution.” He could trace the relationship of the Haitian Revolution to the revolution that brought about Bolivar and the liberation from Spain. It’s a direct connection. They can count how many guns that Bolivar got from [Haiti’s first president] Alexandre Pétion, how many men almost who went with them in liberating Latin America. He makes a critical connection and he makes a visceral connection as well. So those are the people that understand that we need to do this movie, you know? As opposed to the other people, who will tell you: why do we need to go about that? Why do we need to go back there? Or, who’s gonna see the movie? What we have available with technology, “who’s gonna see the movie” shouldn’t be the issue. And yet those are the gatekeepers who keep you out. [Chuckles] This is not Hotel Rwanda. This is something like Gandhi, or Lawrence of Arabia.

The Narrow Frame of Midnight

Could you talk more about the gatekeeper aspect? Because that’s one excuse given for why there aren’t more female film directors: “foreign investors” who don’t like the idea of women directing a film.

Well, part of that scenario keeps women out. And these are the stories that are often male-dominated, male-oriented themes, so you don’t bring in a woman who has another kind of perspective on this story or narrative, who brings in another narrative, because the women’s narrative is a narrative that builds community. Women have the enormous responsibility of family, community; they are the victims of violence, not only state violence by way of war, but also violence within their community. So if you get women directing, and you directed from that kind of female point of view, then that’s a whole ’nother story. They can’t allow that.

That’s the second half of what I was going to say. It’s always this attempt to displace the blame in that, again, these foreign investors don’t want a female director and these foreign audiences don’t want films with black leads.

That’s the part of the gatekeeper. It’s about control. You can’t give people some control over what they see. People have been seeing their lives through the lens of film. And all the things about freedom of choice, et cetera, and all of that—we know the idea of freedom of choice is some nebulous, esoteric thing, when everything that happens to you for the most part is controlled by those who determine what you see, what you think, what you drink, what you dream.

What sort of advice would you give to somebody who is a younger producer, who is trying to change those sort of narratives or diversify what types of narratives are told?

I should say that film does not happen in a vacuum. So the kinds of films that we see in a period of time are dictated by what else is happening around them, where the dynamic or the narrative is being challenged. Culture is connected to real lives, to everyday lives. So if people are challenging what is happening in everyday lives, film in some ways cannot avoid being a part of that. It’s always what the culture has. Let’s take a film about the Montgomery bus boycotts: it wasn’t simply the desire to ride in the front as opposed to the back of the bus. What a film has to find in that, beyond the headlines in newspapers, is a narrative of transformation, how people are transformed by the action itself. That’s the essence of what happened, and the best way it can be expressed is through film, through a narrative that goes beyond the tactic itself. That was not the end, it was not the goal. The goal was the general transformation on your way to liberation.

Film has to capture that. Film has to allow us to see the individual itself within the complexities of the general dynamics, critical dynamics, happening around it. And storytelling is that. What I would consider one of the greatest American films is The Grapes of Wrath. It takes the political situation around a group, against a group of people, and then shows them rebel against it, and you see the variations of their transformations within that. Plays like Waiting for Lefty and Awake and Sing!. Those are great pieces of art about people who are transforming and you see them with their transformation.

To come back to the nuts and bolts of producing, what sort of skills have you felt that you’ve had to develop over the years? What do you think makes a good producer?

Wow, that’s difficult. [Laughs] That’s gonna take me some time. On the one hand, you have to be able to support the vision of the filmmaker, while at the same time help the filmmaker elevate their vision. It happens in different ways, like everything else. I think that as the producer, you also have to be able to articulate the vision, in a way. Sometimes you can’t articulate some parts of it. The visual language of film—and this is the beautiful thing about film—is so awesome, it is so incredible, it is not like any other sort of art form. The juxtaposition of images, and the relationship of images, tell a story in and of themselves, independent of the narrative, independent of the dialogue. So on the one hand, what services me [as a producer] is my intent. My intent as an actor in portraying the story, presenting the story to an audience, is different in some sense than what my intent is as a producer, which is about trying to find different ways of shifting the visual narrative.

I’m concerned about that part of it. How can I move people to think, to use what they see, and use what they feel at that moment to go deeper into the constructs of what they feel? What people feel is an emotional response—I’m trying to get a political response. [Laughs] There’s nowhere in Tala’s film where we’re preaching. She’s created these images of a man’s journey and search, to the point where we feel something from the beginning to the end. I want the emotional response to translate for people—if they allow it—into a political response.