Interview: Claire Simon

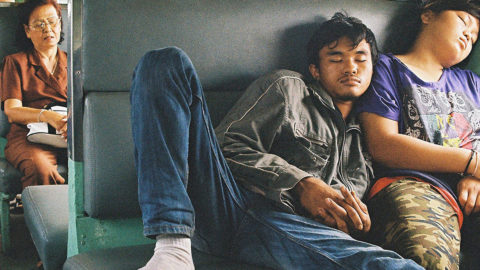

The Competition

After more than a dozen feature-length films, French director Claire Simon received her first major American honor last week: a True Vision career-recognition prize at this year’s True/False Film Festival in Columbia, Missouri. Her latest documentary, Le Concours (showing at True/False as The Graduation but literally meaning “The Competition”), takes viewers inside la Fémis, France’s most prestigious film academy, where Simon taught for years. The film offers a glimpse of the institution’s grueling admissions process, observing the behind-the-scenes discussions between hopeful applicants and jurors, who include the film critic and director Alain Bergala and filmmaker Emilie Deleuze (daughter of the philosopher Gilles Deleuze). Along the way, Simon illuminates the unwritten social, moral, and political stakes behind who gains entrance to this elite institution.

Born in the U.K. and raised in Le Var, France, Simon, 61, began her film career in Algeria, where she studied anthropology and the Arabic language. There she worked as an intern for Mohammed Lakhdar-Hamina; she helped edit his 1975 Palme d’Or winner Chronicle of the Year of Embers. Thus, it was through Algeria that Simon first gained entrance to the world of French cinema, a path which, as she admits, was unconventional, but at the same time “completely logical.” Simon’s subjects often defy easy geographic or racial categorization, an emphasis she attributes, in part, to her transcultural background.

Throughout her oeuvre (which includes both documentary and fiction films), Simon turns up momentous human drama in places that are familiar but nonetheless little-examined—from a preschool playground (Récréations, 1992), to the Gare du Nord (Human Geography aka Géographie humaine, 2013), to the Bois de Vincennes, (The Woods aka Les Bois dont les rêves sont fait, 2015), Paris’s sprawling, seedy public park. Her camerawork is full of long takes and slow-moving or static shots that ground her subjects firmly in space and time, offering a steady and sympathetic structure to set their inner lives in relief. This technique is brilliantly on display in Mimi (2002), Simon’s docuportrait of her longtime friend, Mimi Chiola. Simon reflects her subject’s complex interiority through varied settings in Mimi’s native Nice and the surrounding countryside, peripatetically drawing out her stories and associations with place.

Among Simon’s greatest proponents is her friend Ross McElwee, who, after meeting Simon in France, organized some of the first screenings of her works in the United States. “I have tremendous respect for Claire’s work—and for her as a working filmmaker,” wrote McElwee over email. “The fact that she continues to shoot her own films, rather than employ a cameraperson, is a mark of the intensity of her devotion to the overall craft of filmmaking.” Since 2008, McElwee has regularly invited Simon to speak with his filmmaking students at Harvard, who “never fail to respond to her presence, and are so impressed that she actually knows how to shoot in 16mm, though of course she has now moved on to digital like the rest of us.”

Simon was raised in a family of visual artists and writers; she frequently describes her filmmaking as being like both literature and painting. A niece of the poet and translator Claude Esteban, she would go on family vacations with her uncle and his close friend, Stanley Cavell. It was not until much later, however, that she realized that the Stanley she knew from her teenage years was the same person as Cavell, the philosopher whose writing had become so important to her. The admiration eventually became reciprocal: after attending screenings of her films at Harvard, Cavell expressed his high regard for her work.

Film Comment spoke with Simon after the screening of her film Récréations at True/False. We wandered the streets of Columbia and grabbed dinner, and even though she was jet-lagged and had to catch a 7:00 a.m. flight to get to the Thessaloniki Documentary Festival, she stayed up to chat until the early hours of the morning. Simon was astonished by True/False because the theaters seemed to be full of townspeople rather than cinephile types. “That is a complete achievement,” she said.

In many of your films there is a nuanced and complex presentation of race. And yet, in The Graduation, we are thrust into an environment at la Fémis where race and class are discussed in a completely brute way.

You find it that way?

Yes.

That’s wonderful.

I would love to hear you talk about how you as a teacher at la Fémis observed race and class relations.

I fought extremely hard. I fought to get [Senegalese director] Alain Gomis, the guy who won the Silver Bear this year [for Félicité] in the school. It was a big fight. He ended up being a great teacher at the school and did some workshops, but at first, I remember that the head of the directing department was like, “Who is this guy?” I said, “Look, you don’t know his films, but they are beautiful.” I kept on trying to get film directors from Africa or North Africa or children of immigrants or documentary filmmakers and it was always a fight. But I won. Alain Gomis was at la Fémis for several years, and the students loved him.

It is a small group of people in cinema and they only like people like themselves, of course, because their lives are difficult. They have no perspective. Since the pressure is very high, they always think in the worst way. The whole time I worked at la Fémis, I wanted to bring African filmmakers like Souleymane Cissé—who I think is one of the greatest filmmakers of the world—to the school. He didn’t end up coming, but I thought it was important for the children of immigrants to have role models at the school. But the director of la Fémis ended up agreeing, and he made it possible for Raoul Peck to become the president of la Fémis.

I imagine some people are not happy with how they appeared on screen.

They had a chance to come see and their part [of the movie] in the cutting room, and they could withdraw completely. But they said okay, and nobody withdrew.

So they don’t feel bad about it.

No. They don’t realize they are in the real world. My point was really to show the selection process—do we realize that this is what we’ve done all over the world? It’s our world, let’s face it. What is the machine doing?

How did you get permission to film at la Fémis?

The director of the school said okay, but I had to convince the rest of the people.

How did you do it?

I said it is the right of the citizen to know how it works. You [i.e., the teachers at the school] are paid by their income. You have no right to hide yourself. And it was a scandal, the people who said no. The director [of la Fémis] agreed with me. Who says you have the right to say no?

They all knew that when they were being filmed, it could appear on television and in theaters. But it’s important to be aware of how you are represented even if it’s not filmed. People working in cinema are no more important than a guild of bakers. They are the same. Why do you think you are so important? You are not more important than the people who are making the very best bread for the very best people.

The Competition

It’s fascinating to hear you talk like this, because I could deduce a tension between you as a filmmaker and la Fémis, where there is a cynicism about the project of the school that runs throughout the film. And yet I also perceived a deep admiration for the brilliance of the students and the high level of the intellectual discourse among the jurors. It seems you are not a very didactic filmmaker.

I hope not.

You never really lay out your position in an obvious way. The film itself is quite ambiguous. But you actually do have a didactic position.

Of course. With Wiseman’s films about the army, you have a general who thinks it is a beautiful film for the army, but the pacifist thinks the film supports his view too. The real thing is to understand how it works, and to make a portrait of life as it is. I don’t at all have a journalist’s point of view.

What is it like to make a film about training to become a filmmaker, at an institution where you were once an instructor, no less?

Teaching is a wonderful thing if you are a filmmaker. It is a great moment to stop doing and to think about what you are doing and to invent new things, to talk and receive the point of views of young people who are studying it. It is a part of making the films, for me.

I feel very strongly that I am in the tradition of the painters. They painted what was their environment. That is my heritage: in my family, there were painters. And when I was at la Fémis, in meetings (which were quite boring), I was always thinking, “how is the light?” and “why does everybody want to be in the school”—both the filmmakers and the candidates. And that is a real thing you can learn from painting: how to make portraits out of your reality. It’s very important.

When I arrived here [in Columbia], it was night, and when I woke up in the morning, it was like a Hopper picture in my room. I think filmmaking—and documentary filmmaking in particular—has a lot to do with literature and with painting. You paint what is close to you and you try to make it universal. Vermeer painted his wife and Bonnard painted his wife taking a bath, and it becomes “the bath” and “the woman.” Documentary doesn’t only have to be war, it can be everyday life.

In addition to the painterly and literary aspects of your work, your work evokes another discipline that is deeply enmeshed with documentary film: anthropology. I think of a figure like Jean Rouch…

Yes, Jean Rouch was a great master. I knew him. He was a great filmmaker and he wanted documentary filmmakers to use the camera themselves. He was a wizard of the camera. He liked my films very much. He was very nice. Les Maîtres fous was a masterpiece. And for Godard, [Rouch] was a master—he was a master for the Nouvelle Vague. But he is not well known. He was a great, incredible man.

Human Geography

Watching your films, I am struck by a duality: on the one hand you are an anthropologist, an expert at deconstructing invisible social infrastructures of the Gare du Nord, the Bois de Vincennes, or the children’s playground. But your films all have an element of the personal; they seem autobiographical. I’m interested in your duality as both ethnographer and autobiographer.

But everyone is like that.

Yes, but it seems like it’s your signature.

Of course, all the films are telling my secrets. But they are hidden. I don’t mind. I’m not interested in my story. But they are telling my story of course, as everyone is telling his story. I am not interested in my story, it’s true. It’s not a story.

It’s funny, when The Graduation was released, I had to do a lot of radio interviews where I was asked, “What was your first experience in the cinema?” I have no answers for that. I am more interested in other people. It is much freer for me. I am more interested in other people, in their stories. I’m not interested in my story. I have nothing to say about myself.

And yet you have Ross McElwee, perhaps the most personal of documentarians, telling people to watch your films.

Yes. His work is beautiful. He is the only novelist in moviemaking. He’s filming for such a long time that he can go in the past, and he can go in the present and maybe he can go in the future. He’s got all the tenses that a novelist has, that a filmmaker hasn’t got.

[Ross and I] are very good friends. I showed The Graduation to his students last autumn, and we were together for the Trump election [laughs]. There is a point in common: his story isn’t extraordinary, but he is filming from his point of view his encounter with the rest of the world. That’s why it is so beautiful—it is not at all narcissistic or egotistical. It is the point of view of the novelist.

And you have both made films about your children.

Yeah. And his film [Photographic Memory, 2011] is very strong and very difficult.

You’ve filmed your daughter at least twice—in Récréations and in 800 km de différence [2002]. What was that like?

It was not that easy at one point because it was criticized a lot that I made a film about my daughter. Like Ross was criticized, but from a different point of view because he had problems with his son and I didn’t. It was very different because it was one of the only times I was commissioned to make a film about young people, teenagers. I thought, who else am I going to film?

800 km de différence

It seems overdue that you are only now getting this attention in the United States. It must feel interesting to be on the festival scene in this way at this point in your career. Why do you think it has taken so long for your work to be recognized in the United States?

Because I am not with a big company, because I am a woman, and because I am a documentarian. We are in the minority, the documentary filmmakers, even if we do fiction films. As a woman documentarian, you are a double minority. Now it is not the case, but before, When I made my first short film it was Agnès Varda and Chantal Akerman, and that was it. If you compare Agnès Varda to her contemporaries in the Nouvelle Vague, you’ll see she did things the men didn’t dare do. But she was treated horribly.

Do you feel aware of your gender when you are making films?

Yes, because it is obvious all the time that it is important, in a way. I don’t think about it all the time, but the people in front of me are thinking about it. Because women are raised to be looked at, and as documentarians, we are looking. This is an inversion that is very interesting. It’s complicated. When you see young pretty girls filming, everyone gets a bit nervous. Why does this young girl have the desire to hold the camera? Because she is pretty, she shouldn’t be looking, she should be looked at.

You make both fiction and documentary films. What is it like moving between the two?

I like both, but I think I admire documentary more. It is just a question of money and time, but it is also the question of being free. When you are making documentary, you are improvising all the time. The difficult thing about fiction is that you have to plan all the time, and I hate that. I love fiction but I don’t love all the people that you have to push around in order to be in a real artistic relationship to what you are doing. But both are difficult. But documentary costs less money, so you are freer.

In your films like The Woods and Human Geography you seem to be particularly sympathetic to people who are in-between countries, who have no strong racial or national identity.

Like Obama. He is a genius like that. He doesn’t have a good story. But he took his story and made it a real story as it was not a proper story. It was not a classic African-American story. It was a complicated story. And I admire that. I think he is a great, great storyteller. It is a move to affirm a story that is not stereotypical. You say that I like people in between, but I am completely an in-between person. I admire that in the things he did before being president, like his books.

I wonder if you’ll ever come here to make a film.

I’m absolutely fascinated by this place. I’m very attracted to the way Americans think, how they think about their country, their citizenship.

Your films also pay close attention to those who might be considered outsiders. Was there a moment early on when you felt politically committed to the position of the outsider?

My father was a crippled man. I know what it is to go to a bar and be forbidden to enter. My father had very severe multiple sclerosis. He was a very funny, very loved man, but nevertheless, there were places we couldn’t enter. That was enough. You can see society through illness.

You are an expert at capturing deeply private moments that happen in incredibly public places. In The Woods, for instance, you film an encounter with a prostitute who is completely open to telling and showing you everything. It is as if the camera isn’t there.

Yes, it was love at first sight.

How do you do it?

It’s very simple. I’m interested in other people.

Lauren Du Graf is a Lecturer in English and Writing at Goucher College in Baltimore, Maryland.