Interview: Bill and Turner Ross

Bloody Nose, Empty Pockets by Bill Ross and Turner Ross

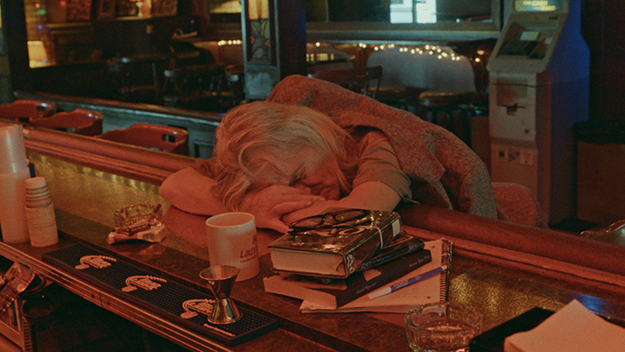

When an old bar closes down, something special dies with it—not just a place, but a place to be. The dive in Bill and Turner Ross’s warmly inviting Bloody Nose, Empty Pockets, screening in the U.S. Documentary section at the Sundance Film Festival, is one such place, dimly lit, filled with mementos and bric-a-brac, and, gradually over the course of the film, filling with people and their memories. It’s closing time for good, and regulars amble in for one final night of drinking and camaraderie, soul-baring and screwing around. But how do you capture that story, really? For the Ross Brothers, some assembly was required to catch lightning in a bottle, so they gathered disparate drinkers together in a bar whose hominess stands in for any roadside bar on the edges of Las Vegas. And much as a bar takes on a life of its own when the hours inch along and the clock melts away, a sense of life takes shape before our eyes here as well.

It’s worth remembering that one milestone in experimental American nonfiction was Lionel Rogosin’s grimly booze-based New York concoction On the Bowery, and the Ross Brothers’ film is rather a sweet dream of a farewell, if at times bittersweet, with old-timers seated alongside younger generations bringing their own baggage. It’s the filmmakers’ most successfully realized and wholly satisfying work since their zip-code-symphony of their Ohio stomping ground 45365, which was followed by a careering look at their current hometown, New Orleans, in Tchoupitoulas; the U.S.-Mexico border reflections of Western; and the David Byrne collaborative concert movie Contemporary Color. Bloody Nose, Empty Pockets has its world premiere on Friday, January 24, at the Egyptian.

This is one of my favorite movies I’ve seen about a bar and the world that gets created within. When you set out to make the movie, exactly what kind of bar did you have in mind?

Turner Ross: In terms of the actuality and the physical structure of the bar, we’ve certainly done our research in dive bars over the years. A great bar has a certain ambiance to it. It can’t be a cold corporate space. A day bar, where people spend time, can have a lot of looks, but we wanted to find someplace that was more like a living room for these people. We scouted Vegas, and I think we’ve gone to every stand-alone bar in Las Vegas. What we started seeing was that a lot of those spaces were being lost. The gritty archetypal alcoholic’s dive bar was being replaced by either something more modern, more hip, more corporate, or by a dignified version of itself, almost referencing itself. We knew that what we wanted to find actually had ceased to exist or had gone the way of tourism.

Bill Ross: The initial idea started right after we had made 45365 and we were living in L.A. We would go on long road trips, and we hated Vegas but the outskirts were interesting because people were either trying to break in or falling out in these bars that were there in ’09, 2010. They were still there but when we went back to make this, they were not.

TR: And that could speak to a bigger thing. You could see those changes all over the country. For us, a bar is an archetypal space, more like a stage, a theater production. So we knew that we needed to create the right stage for these characters to play on.

Do you have favorite bars from home that you love and are kind of sad to see going or have already disappeared?

TR: Many.

BR: Certainly. In fact, we just found out recently that our favorite bar in Las Vegas is closing.

TR: I think it closed January 1st or New Year’s Eve. We thought about running out there and making the sequel real quick.

BR: There’s a saloon underneath this overpass on one of the cross-streets and you can stand there for ages and watch aging drinkers, and it used to have a Chinese restaurant in the back. We could name a place in probably every city we’ve been to. Those places are where you’ll find people, you’ll find stories.

Going back to that idea of the bar as a stage, the people in the film are all able to have their moments. Everyone gets to be someone. Could you talk about the people that you gathered together and what appealed to you about each of them?

TR: Michael [a very former actor and mainstay of the bar] is the character that we really hung our hat on. We had probably a dozen archetypal roles to fill, the kind of people who spend time in these spaces, as well as covering the bases of young and old and people from different backgrounds and how they can speak to each other. We were really trying to build out that bar. A great reference is The Iceman Cometh: if you break it down, those people represent the cross-sections of a lot of experiences in that time. Before we found Michael, we called the character “Jeter,” after the Michael Jeter character from Grand Hotel who was this down-and-out character who was in the bar to have one last go. We knew we needed a guiding light like that who would really embellish the greater theme. We also asked, who’s the greatest day drinker we know? Lo Landon, the long white-haired man.

BR: And who’s his great compatriot? Pam. Sometimes we had a character in mind and then we said, who does this person go best with? So that we could create dynamics, small dynamics within the greater dynamic, then build out from there. They come from everywhere. We knew the guy with tattoos on his face: he’s just a real wild card and we wanted a wild card character. When he showed up to talk about the film and possibly being in it, he had a personal taxi driver, a Puerto Rican guy from Brooklyn. We said, well, I guess Felix is going to be in the movie as well. [Laughs]

We did a lot of casting sessions in bars, meeting people that were there as well as sourcing from our lives. On paper we created what we thought would be the most dynamic cast to put in that space. Then we thought a lot about when these people come into the bar and when they come out. So they actually enter stage right, enter stage left, and the doors of the bar become literally that: you’re coming on stage, you’re getting your moment to say your piece, and then you escape back out into the world.

How did each person react when you described what you were doing?

TR: They really got it!

BR: Yeah, that was the interesting part because we thought we could put together a cast, but we didn’t know if any of this was going to work. But as it turns out, people that spend a lot of their time in bars know exactly what to do once you get them in a bar.

TR: They know the language.

BR: And they know how to move and shake in that space. So about 10 minutes into it, we said, “Okay, guys, the bar is open.” And they just took off. I looked at Turner and I said, “I think it’s fucking working.” I was shocked.

TR: It was an experiment, but I think a part of that is also casting people who we knew could potentially do this and would give up themselves and have their heart on their sleeves. And who had a story that was very available, and a personality that would manifest itself. Also, if one person walks in the door and is the first person in the bar, then that person has already staked a claim—so when the next person comes in, there’s already a logistical story in there. And when those two people are in there when the third and the fourth come in, there’s already a dynamic and they’re starting to build their own story. Then after a certain point, they really started telling their own story and developing their own choreography just out of the naturalism and responding to our stimuli that we create.

So when you’re kind of putting together a general script or a kind of spiritual itinerary—

BR & TR: I like that!

What did that look like when you were sketching it out and in what ways did you depart from it?

TR: “Spiritual itinerary” is good because really it was a script of intention. There were no words on the page. We went in with a beat-by-beat thought process: in this part of the day, these are the things that we think we need to look for, and at this part of the day, this is what we would like to manifest. We tried to create a choreography unknown to the cast so that if Jeopardy! comes on the TV, then they’re gonna do that. Certain people come in at certain times of the day, then they’re going to respond to that. We had two of us to shoot, and I maintained the shooting script in order to keep a trajectory, a sense of our tether: here are some things that we should be hitting and here are the beats that we should be hitting. Bill was there to find what was actually transpiring, so when the film is finished, we can look back on those notes and say, “Jesus, we got pretty damn close to what we had hoped for and what we had envisioned.” At the same time, in doing it we had to respond to wildly different departures, because it is naturalism. We’re provoking a bit but we’re really letting these people be themselves and just respond to their environment. It was a magical experience and a real experiment that I think is strongly going to inform our next film, as all of our films do.

Let’s talk about one of those beats. It’s so moving when Bruce, the gentleman at the end of the bar who’s a war veteran, leaves the bar for the last time. You show him feeling it so deeply, really tearing up.

BR: That’s a genuine emotion. Bruce really wears his heart on his sleeve. We found him at a bar at two o’clock in the morning when we were casting for the film. When it came time for that [moment in the film], I just reminded him of the stakes. I said, “Bruce, this is the last time that you could come to this bar, and you know you often talk about bars and the family you could build here. This is the last time you say goodbye.” He just burst into tears, genuinely. He’s not an actor. It’s just a real sentiment that he had.

What were some cinematic touchstones for you that have really captured some of these feelings of life in a bar?

BR: Have you seen that UCLA is doing an American neorealism show?

Yes!

BR: Someone sent me that the other day, and I thought, these are all our references for Bloody Nose, Empty Pockets. Dusty and Sweets McGee, The Exiles, On the Bowery. Lions Love (…and Lies) by Agnès Varda was a really big one… What else was our cheat sheet?

TR: Eugene O’Neill…

BR: Fat City is a great one. That probably has the best bar scene of all time. So real.

What is it about these ’70s movies for you—because even in the opening shot, you’re referencing a certain era of filmmaking with a long wide street shot, waiting for someone to walk into the foreground. What are you tapping into there?

TR: Those films just feel so lived in. And they feel hand-made. I feel much closer to the screen with a lot of those films—like I can feel the filmmaker. And we aspire to make these tactile, humanistic films that are so inspired by a certain era of film that has that same character and grit to it.

I noticed a number of movies playing on the TV in the bar. I kept on trying to figure out what it was, in the second or two we’d get a glimpse. It really looked like Touch of Evil at one point.

BR: That’s weird because some of the stuff on the TV was programmed and some isn’t. I always love a bar when there’s dancers or movies on the TV. I know exactly the shot you’re talking about because it does look like Orson Welles.

Also thought I saw Potemkin and The Exiles at another point.

BR: No, The Exiles I thought was too obscure to program on there, although that was a huge reference.

How long did it take to edit Bloody Nose? How did it evolve, and did you vary on how polished or rough you wanted it all to look?

TR: It was off and on for two years. It started out being very, very rough. We had some very confused ideas in the beginning. [Laughs] Our favorite cut was four and a half hours. It was by far the toughest edit [we’ve done], and going into it, I thought it would be the easiest because it’s a point-A-to-point-B movie.

BR: We had a game plan.

TR: As it turns out, spending 12 hours with drunks every day is very hard. [Laughs] It was very tough to deal with, and we didn’t know if it would work. The majority of the edit, we had great uncertainty if we had anything or not. Up until recently, I wasn’t too sure.

What clinched it for you? When was the moment when you went, okay, this is crystallizing in some way?

TR: I don’t know if we should say this: we locked ourselves in a hotel room one night and took acid and watched it. And I could actually see it for what it was.

Wow.

TR: At least I thought I did. [Laughs] So I was seeing it with sort of fresh eyes, and I was like, “Holy shit, I’ve never seen anything like this.”

BR: And then it took six more months of editing.

TR: And then it took six more months of editing. But! It gave me faith.

You saw through to the soul of it and saw you had something.

TR: Yeah, I think so.

BR: You had to see through it, because we had a strong game plan, and then we watched all of the footage and said, well here’s the story that we got, how can we put those two things together? And the literal execution of that wasn’t satisfying. We finally had to get into it and break it down into this movie which you’re highlighting some of the characters and their stories are succinct and important. As I said, we could sit through a four-and-a-half-hour version of this and we really enjoyed the space and the mood and the feel of being there but at some point…

TR: You know, like when you watch Husbands, it’s such a good movie, but it’s three hours long and it should not be three hours long.

The actual shooting in that space, how many hours was that?

TR: There was a primary 18-hour nonstop shoot which is the bulk of the film. Then we learned from it and then came back with the natural extensions of what that would be and then pressed go again. We would just keep doing that, including the exteriors in Vegas, so that it was following its own reasoning. So that if something happened in this big shoot we needed to continue to embellish it, that would be the scenario for the next shoot. And there’s some footage in the film from those initial scouts [in Vegas] that Bill and I did.

BR: Yeah, a lot of those color pieces are what were shot on the streets 10 years ago.

I’m also curious about another aspect, because, of course, Sundance has a Dramatic category in addition to a Documentary category. Obviously, to a certain extent, these are just labels for films, but what’s stopping you from submitting your movie to a festival in a dramatic category, and opening people’s eyes to what you’re doing there?

TR: I think we could have. Like you said, I don’t give a shit about these labels—we are documenting this experience. The truth of it is, when it came down to it, Sundance is a great platform for press for us, so we decided to go with them. Their team was excited to program it as a documentary. There was also a push to not screen it as a doc. For us, we aren’t interested in getting into the conversation about what is fiction and what is a documentary—I think that misses the point of what we’re after here. But if people go in looking for those documentary elements, then maybe that emphasizes what we’re actually trying to do creatively, rather than looking at it as a fiction film and thinking that all the decisions were pre-ordained. We didn’t want to be in a scenario where people were going in thinking that these humans were completely scripted and directed. But again, we’ll leave that up to smarter minds who write and talk about these things and want to have that discussion. For us, this is the way that we wanted to make this film, and that’s the only way we thought we could make it.