Interview: Arnaud Desplechin

PEER: Where was I, as myself, as the whole man, the real?

Where was I, with my forehead stamped with God’s seal?

SOLVEIG: In my faith, in my hope, in my charity.

—Henrik Ibsen, Peer Gynt

Constructed like a symphony which bears echoes from his entire oeuvre, My Golden Days is Arnaud Desplechin’s most elaborate and personal reflection on what it means to be a man. Two decades after the university-set My Sex Life… or How I Got Into an Argument (96), Desplechin reunites with his alter-ego Paul Dédalus (Mathieu Amalric), but time has passed and the young normalien has grown into a fifty-something anthropologist who now resides in far-off Tajikistan. As he prepares to return to his native France, Paul is stopped at customs over an identity issue: “We have found another Paul Dédalus!” the inspector roars. There begins a Proustian journey into the forgotten depths of childhood and youth, all memories pointing toward the quintessential period in Paul’s existence: his love story with Esther (played by Emmanuelle Devos in My Sex Life and newcomer Lou Roy-Lecollinet in the latter film). “Everything is intact,” old Paul repeats as he conjures up his golden days, a utopia centered on Esther and Esther alone, where past and present coalesce in alternating waves of pleasure and heartbreak.

On the day of the U.S. premiere of My Golden Days at the New York Film Festival, Film Comment spoke with Desplechin at the Film Society of Lincoln Center about his writing process, Catcher in the Rye, and Roy-Lecollinet’s magnetic performance.

I have the impression that your relationship to story and your narrative approach have constantly changed. My Sex Life had a very loose, jolting structure, almost determined by the character’s stream of consciousness, and the actors had to put together a puzzle because the story would continually jump around in space and time. And then with Kings and Queen, you once again made a tapestry, a kind of patchwork. But the structure became much more precise: all of the scenes began to converse, to reflect one another. I feel like with My Golden Days, you’ve reached the height of this precision because here you really have a continuous linear progression. And that perhaps has to do with the fact that for the first time you’re examining a process of construction and not of collapse: the construction of love, and love is inextricably linked to duration. What made you want to operate this way?

It’s exactly what you said. I couldn’t describe it better because my writing method is very intuitive. I had this sort of double desire: on the one hand, have something that’s very constructed, very linear, and at the same time, to fracture it into three uneven blocks. So there were these two simultaneous desires. The goal was not to abuse the spectator but to have three pieces of film and paf! a long story, and at the same time to make sure that these three pieces of film would feel like three brutal spurts and still manage to draw a single journey map. And then there’s the tapestry, like you said… I like that the three fragments have a very strong and unique identity of course, that they don’t stick together too well but that they don’t knock into each other either.

And then within the construction, there is an entire work on what I call the motifs, what I called during the writing process “the song of the film”—this idea of having a single song traverse these four or five different films that are glued together. I tried to work with blocks and then obviously to speak to the spectator, I tried to find the song that would fit together these scattered pieces.

It’s as if Paul is saying to us: “I’m going to recount one memory very quickly, then a second a little less quickly, and then with the third, I’m really going to take my time.” And it’s funny because one could compare the form of the film—this three-part division—to the stripping off of clothes. You don’t show everything right away. First you take off your shirt, then your pants, and finally your underwear. At the end, Paul is completely naked in front of us.

Yes, at the end Mathieu is naked. At the end when he speaks with Kovalki [his childhood friend who tried to steal Esther from him] at the café, he’s taken off all his clothes. It moves me that he gets to that point… That with the third story, he gives way to Esther, that Esther invades and cannibalizes the film. And Paul is only Paul because he gives way to Esther, because he erases himself next to her. I really didn’t construct this film in reference to My Sex Life even though there are motifs and characters that have passed from one film to the other. Yet I remember that at the end, the old Paul was dead because Esther had taken up all the space. And so he has to die and disappear from the picture so that Esther can appear. And it’s when Esther appears that Paul finds a reason to live. He manages to be invented by a woman.

This reminds me of Peer Gynt, which seems to traverse all your films from Esther’s monologue in My Sex Life—where she speaks as Solveig—to My Golden Days, which has a pretty similar arc to the play. Peer’s quest is reminiscent of Paul’s: he travels the globe in search of a home only to realize that home is by Solveig’s side. So he goes back and dies in her arms.

Yes, and there is also the clumsiness. Mathieu says a line at the end of the film that moves me a lot: “All things aside, the only thing I’m not certain of is whether I’ve been good to her or not.” And when he says that, it’s really devastating to me because how could one ever say: “Yes, I’ve loved someone.” You have to be very presumptuous to say that. Because how could you know whether you’ve loved them good or bad? How did you really love them? Maybe you’ve messed up and you’re cheating yourself. And so for Paul, it’s this question, this anxiety that keeps him alive, that keeps him vigilant. And so he asks himself: “Was I capable? Did I succeed in this?” And he never allows himself that certitude.

I know that you work with a “corpus” when you’re writing. What were some of the films that guided the writing process for My Golden Days?

You know, we start the “corpus” with a few films and then it gets bigger and bigger to the point of becoming completely incomprehensible to someone who’s not participating in the script. [Laughs] There was one film that mattered to me a lot and that goes back to a historical memory. Coppola had made two films in Tulsa: The Outsiders and Rumble Fish. At the time French critics thought that Rumble Fish, which was a very European film, was wonderful and that The Outsiders, which was very American, was a very bad film. I was completely shocked in the theater because I thought that The Outsiders was pure genius whereas Rumble Fish to me was more of a poser, a film that I never really liked anyway. I watched it over and over again but it’s not my thing. But in The Outsiders, there was really a momentum, a naïveté that struck me. And also these young people who live without adults, who expel the adult characters from the film. There was this sort of strength in the film that made it very precious to me.

So there was that film, and then there were two Milos Forman films: Loves of a Blonde and Black Peter. Loves of a Blonde is the film that I showed to the crew before the shoot—I always show the actors and technicians a film—and said: “This is what we’ll try to attain.” And then there were other films of course. There is a film that counts a lot for me: Caro Diario. Not even in terms of the writing but for more idiotic reasons: there are three stories. But it’s not the same thing at all because the three stories in Caro Diario have roughly the same duration and they are ruptured. It’s really a Russian doll, that is to say, everything interlocks. So it wasn’t the same thing. But at the same time, you can’t compare apples and oranges, you can only compare apples and apples.

There were two films—perhaps situated at the opposite ends of the spectrum—that I thought of a lot while watching My Golden Days: Larry Clark’s Kids and Bergman’s Fanny and Alexander. For me, My Golden Days was really a synthesis of the insolence and rage of Kids, and Fanny and Alexander’s innocence and naïveté.

Larry Clark, especially with Kids but also with Another Day In Paradise, is a filmmaker I love. I’m just stunned by his talent. But at the same time, I kept at a distance because it didn’t correspond to the desire I had. Something I admire in Larry Clark’s cinema is the desire he has for his actresses and his way of being documentary with young people [i.e., his way of documenting young people]. What I shot in my project—which was different from a project by Larry Clark, that I admire—was to say: is it possible for you, young people, to welcome the fantasies that I write? Can I talk about you through myself? Whereas Larry Clark has this genius of talking about them with their own voice, of managing to “steal” them. There is a kind of eroticism in this theft, you know? But my approach was different in that I was asking myself: will I be capable of dialoguing with such young actors? I’m thinking of Lily Taieb [who plays Paul’s sister, Delphine] for instance: she was only 14. So I was asking myself: could we talk as equals, work together, invent gestures, attitudes, emotions together? In life it is obviously very difficult to cross this generational barrier but here there was this sort of utopia that I had dreamed of and that worked.

Fanny and Alexander is the film that’s accompanied me all my life. La Vie des Morts [91] is a complete rip-off of that film anyway. I stole everything from Fanny and Alexander. It’s a film that never stops nourishing me—both the theatrical and TV versions. The whole principle of generational stories comes from there. I watched that film and it allowed me to make films myself. No question about it. Of course, among the most beautiful Bergman films I would count Summer with Monika—which was in the corpus. Wild Strawberries is one of the most beautiful films in the world. But I have a special attachment to Fanny and Alexander, given also the age I saw it and also because I’m French and the film was a French co-production. I saw Fanny and Alexander and then I became a director. Before, I was a technician, and after that film, I became a director.

One of my favorite scenes in the film is the museum scene in which Paul compares the Hubert Robert painting to Esther. First of all, it’s a magnificent text, surely one of your most lyrical pieces of writing. Also this idea of projecting the loved one onto a painting is an act that’s truly worthy of a poet and a candidate for one of the most beautiful love declarations in French cinema. I’m curious to know how you worked on that text—probably the densest passage in the film—with Quentin Dolmaire, and how you generally approached the text with these two young actors who keep saying that people don’t speak like that in real life?

[Laughs] You know I don’t do rehearsals. I just don’t. So we don’t work on the text, we work on other texts. For that one, he was a little young honestly… And there were also all those mythological references. So I had to teach him who Nausicaa and Actaeon were, and I didn’t want to crush him with those because that wasn’t the question. I was more interested in seeing the colors of his emotions and how he takes up Esther’s challenge. Also his fear of speaking, of expressing himself with words. When he begins his tirade, he says to himself: “I may not be able to pull this off.” Also there was this beautiful question of “Will I be able to describe? Will I be able to compare what is not comparable?” So Quentin practiced this text a lot with the first AD to know it by heart. That’s extremely important. It’s something I learned from Mathieu, to really know your text like the back of your hand. And that sounds a bit idiotic and humble as the actor’s work because of course you have to know your text. But really, to know it like the back of your hand. To really be able to say it in one way then in reverse, begin saying it from the middle, from the end, to know it like you only knew that. And that’s the kind of work that reminds me of My Sex Life because it was a nightmare to get Mathieu to learn all those articles. And there Mathieu had two monologues as well, so it was the same work with Quentin to really master the text. Only memorization, only memorization.

When you succeed that—which is a pretty long process—you can begin to work on the seduction, the pleasure, on the vanity also. When Esther says: “You’re a smooth talker,” Quentin’s exquisite response is: “Not bad.” So he’s successfully performed the task. And it moved me also because Hubert Robert was Stendhal’s favorite painter and I thought the film had a very Stendhalian color.

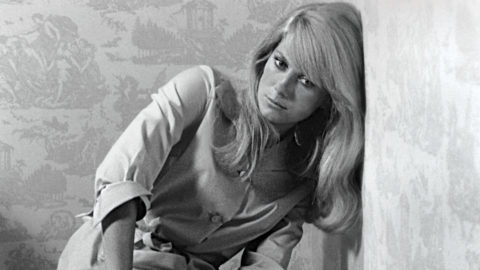

Another moment that struck me was Esther’s arrival at the party. There is something electric in that girl’s presence—she really is Kim Novak in Vertigo! Whenever she goes on stage, she absorbs all the light around her and one wants to watch only her. There is also the fact that your camera is often glued to her face and it’s more her look that tells the story rather than her words. Was this desire to stay close to the faces already present at the writing stage or did it appear with the discovery of the actors?

No, that appears with the actors. I have notes of course. But when I’m writing, I try to make the story work and I have little time to think about how it’s going to look. Of course I have vague ideas about it and I’m going to draw on these ideas when I shoot. But we rarely talk about the fabrication of a film during the preparation. And then when the actors come on board, they’re going to change my perception of the script, incarnate it, give it a shove. When you find actors to incarnate your characters, you know you’re going to film them and I try to let myself be affected by that. I try to get close to them, just like when I asked Quentin to master his text. I’ve got my tricks. So in that scene, I run the camera in slow-motion when Esther arrives and then it returns to normal speed when she meets Bob. So I have my old tricks, things that come from my background as a technician. It’s all about letting yourself be affected by reality and allowing it to modify your breakdown of the scene.

There’s another shot that’s not too far from this idea. It’s a very beautiful shot because I hadn’t rehearsed it. So, you see, Louise [Roy-Lecollinet] didn’t dance. She is a more melancholic girl. She’d just had a difficult year at high school and she was 17, so she didn’t want to dance. And I was telling her “If you don’t dance at 17, when are you going to dance?” So we had dancing lessons, we did the choreography of the dance and all that. But she was still a little embarrassed so I told her “Dance like me and that’ll do it,” and it happened progressively. And on the day of the shoot, I had planned the shot and everything but suddenly her face called me and I said to Irina [Lubtchansky, the cinematographer] “Hand me the camera please,” and I went for it. And I had to hurry to get her face, to move close with the camera on my shoulder. I had asked Quentin to play right next to me so I panned to him afterward and he had the most devastating look of the film on his face. When he looks at that girl, she exists so much and he exists so little. And the camera goes back to Esther still dancing and again rushes on her face. So on the one hand, there is a preparation process and on the other, this idea of allowing yourself to be affected by the actors’ performance so that they come and ruin all of the cautious planning you might have done, that they shatter it with their sheer presence.

The final part of the film, which focuses on Esther’s depression, really involves a continuous one-on-one between Esther and the spectator. It must have been extremely tough for someone who’s never acted on screen before to have to confront the camera so directly.

Yes, extremely. It was crucial that what happens with the character happens with the actress too. So on another plane it was the question of how to make her take control of the film, because that means becoming the film. That is to say that at the end, when Esther has her depression, she is the whole film. All the rest, the childhood memory, the episode in Russia melt away. She’s taken up all the space, she’s swallowed up everything. And I had this image in mind of a girl who takes up all the space in bed.

That’s not true, it’s men who take up all the space.

But that’s precisely Esther’s singularity. She takes up all the space. And he is delighted that she takes up all the space, that she becomes so cumbersome. So how to make her cumbersome? I remember a rendezvous we had with Louise before the shoot. I was telling her that for that section she really is going to have to hold on to me because otherwise she wouldn’t be able to make it. I told her “You have to take control,” and she said “I don’t want to take control.” And I said: “But you’re here for that. That’s why I invited you on this film, so that you take control of the film.” And I told her that she had to go for it, that she had to cry, give in, scream, that we needed to get Esther’s song heard. And then it was all about creating that utopia I had dreamed of. This dialogue was forged between us, people from two different generations. It was really beautiful to arrive at that, to film the rise in power of this actress. She allowed herself to ramp up like that and she was surprised at the end, saying: “Damn. I really know how to embody this character. I know how to do it. I know how to use Esther’s distress to talk about my own distress.” And there I had this writer’s pride that my words had served someone else.

It’s very moving that you’re not only shaping a character but also an individual.

Yes, but we’re two in doing that. And that’s what’s magical in cinema, this rise in power. I told her: “You have to cling on to me. I’m the only person who can get you through that scene. I’m sorry but we’re going to have to cooperate.” And so that created a very powerful bond between us. And there’s also something else that moves me a lot. Paul loves Esther because she is indestructible and Esther is crazy about herself because she is indestructible. And then love comes and she wants it to come and suddenly she becomes vulnerable. She hadn’t anticipated that, she didn’t know she wanted to become a heroine. Of course she wanted to become queen Esther. But there is a price to pay and that price is the distress at the end. And in Louise’s performance, I see the price to pay. She has no defense anymore, she’s lost it. She doesn’t know where she is anymore because love has arrived and suddenly she is fragile, this girl who was so unbreakable at the beginning of the film.

And there’s also a moment that moves me a lot. Esther says to Paul, “You’ll call me,” but Paul doesn’t have a phone in Paris, so he answers, “You’ll write to me.” And there is this tiny second there… We think Esther is not the type of girl who’d write letters. But at the same time, she slowly understands that she is going to write and that she’s going to become a writer. She’s going to become the writer of herself, the novelist of herself. But then again, she didn’t anticipate her vulnerabilities and her armor comes undone and she explodes.

Emmanuelle Devos—who plays Esther in My Sex Life and with whom you’ve worked on practically every film you made—is not in My Golden Days. But there is a very moving moment at the end of the film where she seems to inhabit the frame. When Mathieu Amalric is walking on the street and those Greek pages fly on his face, it almost feels like Devos is the wind that blows that night, that she manifests herself through nature.

Yes, that’s true. She’s missing from the film. And the film was constructed, I had the occasion of telling this once, upon her absence. She had to be absent so that the film could exist. The film is constructed upon Paul’s regret that she’s not there. It’s very melancholic that she’s not there but at the same time it’s necessary. It’s all about Paul’s saying to himself: “It’s very stupid. I shouldn’t have let her go.” But no, she’s not there. And that’s why we finish with the Greek lesson, that moment imperfectly comes to make up for her absence.

Paul Dédalus often reminds me of Holden Caulfield in Catcher in the Rye. His solitude, his melancholy, his interrogations, his continual battle against life and himself… His way of constructing his identity against society. Even the way he speaks, this mixture of a terribly childish jargon with a raffiné and almost scholarly language. What is your relationship to that book, if any?

Actually, my relationship with Catcher in the Rye happened in reverse. Two people, an editor and my girlfriend, told me not too long ago—it was before this film actually, three or four years ago—“You have to read Catcher in the Rye because you never stop adapting it.” I had never read it before, I guess I’d been too caught up in the books I read at school. And there’s something in what you said that I experienced through different detours and that I discovered much later in Salinger’s book. I always think of this sentence by Serge Daney that’s marked me so much and that seems to inhabit Salinger’s oeuvre as well: “To be in the world but not in society.” This refusal of society, this desire and curiosity that Paul the traveler has to go all the way to Tajikistan to discover the world, to be in the world but not in society. That’s something I learned from Serge Daney and years later, it was an editor—Olivier Cohen from the Editions de l’Olivier, which has a great collection of Salinger—who told me: “Well, read it since you don’t stop adapting it.”

Translated by Yonca Talu.