Interview: Anna Karina

Examples of filmmakers haphazardly discovering their muse abound in the history of cinema. In France, two such stories from the Fifties have come to be popular legends: Roger Vadim’s accidental discovery of 15-year-old Brigitte Bardot on the cover of Elle magazine (the director happened upon Brigitte’s picture while making a paper plane from a page of the magazine), and Jean-Luc Godard’s chance encounter with 19-year-old Anna Karina through a Palmolive soap commercial, which marked the Copenhagen-born Parisian actress’s first on-screen appearance.

Both of these episodes prompted the formation of two of French cinema’s most influential actress-director couples: Vadim turned Bardot into an enduring symbol of female emancipation, while Godard made Karina into the face of the country’s most radical and revered cinematic revolution.

In the seven and a half films they made together (Karina counts the 1967 short film Anticipation as half a film), Godard filmed his spouse from all angles, delineating her feline beauty with the precision of a portrait painter. Each Godard-Karina collaboration is a portal into the latter’s soul. A Woman Is a Woman (1961) was an overt celebration of Karina’s youthful impetuosity and playfulness, while Vivre sa vie (1962) highlighted her emotional depth and gravitas under the traits of doomed prostitute Nana. In Bande à Part, she was a frail gangster, and in Pierrot le Fou, a carnal and impulsive femme fatale who orchestrated her literary lover’s bloody destruction. Whether it’s Angela, Nana, Odile, or Marianne, the women Karina portrayed were beings of instinct, madly engaged with life and who laughed, danced, sang, and fought until their last breath, in praise of freedom.

In early May, Karina made a special visit to the United States for a spotlight on her career with Godard, including screenings of A Woman Is a Woman, Bande à part, and Pierrot le Fou. FILM COMMENT spoke with the lively and gracious 75-year-old in New York about embodying Nana, Jacques Rivette’s La Religieuse, and the eternal fusion of fiction and autobiography in the films of the pioneer who invented her as an actress and reinvented her as a woman.

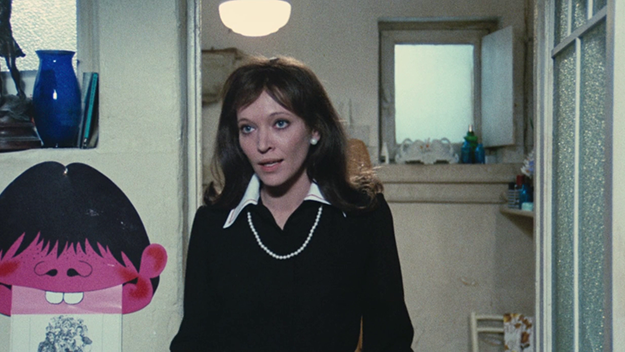

La Religieuse (Jacques Rivette, 1966)

Let’s start with Bande à Part since you are in New York on the occasion of that film’s re-release. Between Vivre sa vie and Bande à part, you went through a difficult period [Karina was hospitalized following a suicide attempt], and you later said that Bande à part saved your life. In fact in that film, you look very vulnerable, like a porcelain doll about to shatter at any moment… How do you remember that shoot?

Yes, in a way that film saved my life. I had difficulties at that time to live my life. It was pretty difficult between Jean-Luc and me. I was in the hospital, and not a very good one. And Jean-Luc came, took me out, and said, “We are shooting the day after tomorrow,” and I said: “Okay.” And that’s how Bande à part came about.

The film is like you and Odile’s shared cri de coeur: at bottom, it is the story of a woman who fights with all her strength to live.

Yes, you can say that. Nobody said that before!

How much did Godard direct you on that film and how much did he leave you to your own devices?

Well, he gave us the lines at the last minute, like always. But we were already familiar with the subject matter: the story of three little gangsters, and I was the naive one among them, a girl called Odile. And we went to English classes: “tou bi or not tou bi against your chest, it iz ze question.” [Laughs]

Claude Brasseur wrote that line to you on a napkin.

Yes, that was great fun! Godard never said you have to do this like this because in a way, it was all in the action, you see, in the dialogue. He didn’t have to explain it. Even with the cameraman, Raoul Coutard, they never really spoke to each other. They just knew what they had to do. I know it’s very special because I’ve worked with many directors, classical ones, you know, and it was very special with Jean-Luc Godard. Very special, because he didn’t have to tell us what to do really. It’s like, if you have to say “Hello” in a nice way, you don’t say “Hello” like this [She says it with an angry tone]. It was just natural, the movements and all that.

Okay, the Madison, that we rehearsed for about three weeks in a nightclub every night after the shoot from 7 to 8 and sometimes from 8 to 9, because the nightclubs never opened before midnight. So we went there with professional dancers and did the hand clapping and finger snapping. [She snaps her fingers and claps her hands.] We had to do rehearsals because the two guys, Sami Frey and Claude Brasseur, didn’t know how to dance. So we rehearsed that scene for a long time, and it became a long take in the film, about three minutes or so.

Every time I screen the film [Bande à Part], the guys in the theater mumble the song and start snapping their fingers. Anywhere in the world, be it London or South Korea. In Australia, there is this pizza place called Bande à Part, and I have my special pizza called “Anna Karina.” I went there once, ate my pizza, and danced the Madison. They also have a pizza called “Jean-Luc Godard” and T-shirts with pictures from the film. It’s very cute!

And recently I went to Bergamo, Italy, to screen the film. There were only teachers there. It was 6 in the morning and a full house. I also went to London and met fans who had tattooed my name on their arms. I couldn’t believe it! Then we went to Switzerland and Denmark where I got the Bodil Honorary Award for everything I did. It’s been quite a journey and I’m used to it, you know, because I used to sing with somebody called Philippe Katerine and we traveled all over the world, including Japan and Spain. It was great fun, for eight years. We went to Brazil too: there were 1,800 people in this big, big, big place and we were like small pigeons on the stage. I just came back from Italy. With Dennis [Berry], my husband, we used to live in Italy about 30 years ago. It’s changed a lot. When I was there now, I searched for our house—we used to live in a little wooden house on top of a mountain—but it was not there anymore and there was a kind of building in its place. It was so strange to see it changed that much.

Bande à part (Jean-Luc Godard, 1964)

Aside from acting and singing, you also wrote four books and directed two films—your book “Golden City” came out in the Eighties so you must have written it while you were living in Italy. What triggered your desire to write? Was it a sort of escape from cinema?

I’ve been writing short stories since I was a little girl. I left school when I was 14. But I always liked to write. So when I was living in Italy with Dennis, I didn’t know what to do—of course I spent time with Dennis and took care of the food and all that, and my father in law would come to visit. But then I said, I would like to write a book. So I wrote my first book called “Golden City.” Just for, fun in a way. It was 500 pages long, but they cut it down because it was a little bit too long! It’s a kind of thriller with gangsters.

So it has echoes of Bande à part.

Yes! It takes place in San Diego, and I invented a city called “Golden City.” It also took place in Mexico—I knew it a little bit because I went there a long time ago for a film festival. So I wrote this book and it came out in France. And after that, I wrote a second one, and then a third one, and some musicals and songs too.

What about Victoria, the film you directed in 2008? Did you write that because you wanted to act again?

No, the producer Hejer Charf, whom you just met [Karina came in accompanied by Charf], wanted to make a film again. So I said: “Okay.” But I wanted to do it in French with French actors—it’s the story of a woman who comes to Montreal and doesn’t really understand what’s going on. But the French actors couldn’t do it because of the quota, so I shot it with two Canadian actors. So it’s not really the film I imagined to begin with. It’s about an amnesiac woman who travels in Canada. She doesn’t know who she is anymore, she forgot all her memories.

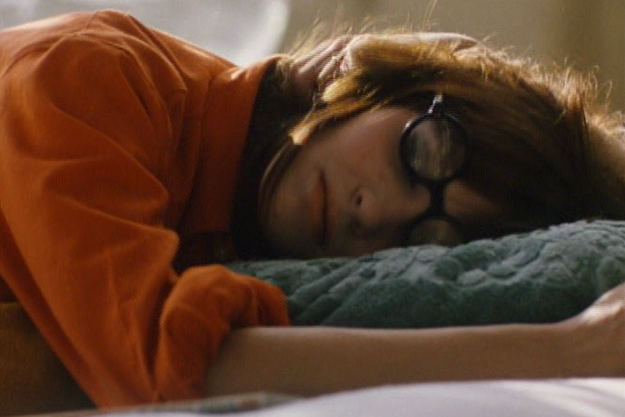

You mentioned the Madison scene in Bande à part earlier, which brings me to another iconic dance scene, the swing in Vivre sa vie. I watched the film again and was very moved by that scene—it just introduces such a breath of youth and cheerfulness into the otherwise somber and rigid film. It’s refreshing to see Nana take charge of her destiny, even for a short while. Can you talk a bit about the shooting of that scene? Are you the one who came up with the choreography, or did Godard do the blocking with the camera and then ask you to dance along?

I totally improvised that and then Godard followed me with the camera. Raoul Coutard is a great cameraman. He could follow anything, he’s really a genius. They liked that scene a lot in Brazil!

Another quintessential scene in Vivre sa vie is the philosophical conversation in the cafe. How did Godard write that scene? Was it one of those scenes he wrote the morning of the shoot, or did he write it in advance and give you guys enough time to absorb it?

He was very smart about that scene. He talked to the philosopher first, Brice Parrain was his name, and then he talked to me. He wrote down some dialogue for me, and then I sat in front of Brice Parrain and said the dialogue Jean-Luc had written for me. It was all written by Jean-Luc Godard, except Brice Parrain’s lines. He was saying what he wanted.

Vivre sa vie (Jean-Luc Godard, 1962)

So he was improvising?

No, he was being interviewed by Godard like I’m talking to you right now. So Jean-Luc talked to him first and he would say so and so and so. Jean-Luc would write that down, and then I would take Jean-Luc’s place and say what he wanted me to say. Jean-Luc was very smart about that scene because had I just talked to Brice Parrain myself, I wouldn’t have said the same things and he wouldn’t have given me the same answers. The way Jean-Luc shot it looks just like we’re speaking together, but it’s not the way it was done at all. We shot that film very quickly, in about three weeks. That scene was shot in a few hours. Everything was very quick with Jean-Luc because he got bored quickly, so everything had to be done fast. Except for the Madison!

The philosophical conversation in Vivre sa vie feels like a precursor to Pierrot le Fou. When Nana says, “The more one speaks, the more words lose their meaning,” she’s like a younger version of Marianne Renoir when the latter says to Ferdinand, “You speak to me with words but I look at you with feelings.” For many, these lines are autobiographical, and it was you, Anna Karina, who said them to Godard. At the time of the shoot, were you aware of the parallels between the script and your private life? In a way, all of Godard’s films from those years are letters to you…

I didn’t really think about that at the time. Of course, I knew it, but I didn’t think about it. You know, Jean-Luc was like that. He would write me beautiful letters but then I wouldn’t see him for three weeks because he would go out to buy cigarettes and never come back. It was very strange. He would suddenly leave, and then I would be sitting there in front of the telephone, waiting. It’s not the same thing today where everybody has smartphones and you can call anybody anywhere in the world. Back then, you had to talk to a lady and say, “I want this number. Can you give it to me?” And then you would wait for half an hour. It was another world. And when Jean-Luc left, I was all alone so I started to paint and all that.

Did you also write?

No, because I was married to somebody who would write everything down and I wanted to get away from that. Once we were going to Denmark for Christmas together to see my mother, and Jean-Luc wrote a lot on the plane. And then when we got to customs, they said you cannot enter the country, because Jean-Luc had written in his passport and had ripped off the page! So he couldn’t get into Copenhagen. I was crying, you know. It was Christmas, and he had to go back to Paris. He was sent back because he was trying to enter the country with a broken passport. It was a nightmare. So I was waiting and waiting and waiting, and two days later—it was Christmas and the Embassy was closed—he came back! He came back, and I went to get him. I never understood how he did it. But then I thought about it and figured it out. He was born in France, right? So he has a French passport. But he lived in Switzerland so he also has a Swiss passport, so maybe he went back to get his Swiss passport and then came back with that. And he didn’t write in the passport this time. He would do things like that. He would say, “I’m going out to buy cigarettes,” and then disappear.

Where did he go?

I didn’t know, and I was waiting and waiting and waiting. Sometimes I understood he was in Italy—he had gone to see Rossellini—because he came back with writings in Italian. Sometimes he went to London or to Sweden to see Ingmar Bergman. Or he went to see Faulkner in New York. And I understood because he would come back with things written in English or in Swedish. And he always came back with a present. Three weeks later! At that time, there was no phone, no answering machine. I’m talking about the ’60s—you weren’t even born then!

Bread and Chocolate (Franco Brusati, 1974)

I was far from being born! To change gears a little, I also wanted to talk about the Italian films you made. In Bread and Chocolate (1974), Franco Brusati’s marvelous tragicomedy on immigration, your performance is fascinating through your ability to constantly shift back and forth between humor and grief. How did you join the cast of that film led by Nino Manfredi?

Brusati came to see me in Paris, he liked my films and proposed me the role. But Nino gave me a box of chocolates and I gave him a piece of bread! Nino was a very nice person and very funny too. He had great scenes with chicken in that film, and the film was a big success. It got big prizes all over the world, including from the Church, because it talked about immigration. It’s like today, you know. In the film, Nino has to find work in Switzerland to feed his family in Italy. It’s very political in a way and very human.

You’re also the face of one of the most controversial films of the ’60s, Jacques Rivette’s La Religieuse. This film, which was considered blasphemous at the time because of its depiction of homosexuality in a convent, originated as a play in 1963, and after being banned for two years, finally came out in theaters in 1967. What are your memories of that shoot and how did you experience the period of censorship?

I really worked a lot for La Religieuse because, you know, I’m not French. And when I came to Paris, of course I couldn’t speak French. So I went to the movies to learn French and took lessons and all that. And when Jacques Rivette asked me to do La Religieuse, I worked day and night to speak this language Denis Diderot had written centuries ago. So we did it on stage to begin with.

Did Godard direct the play or Rivette?

No, Rivette directed it. I heard many years later that Jean-Luc produced it. I didn’t know, he never told me that! It was like a present. But I didn’t know, I swear I didn’t. He was like that, very secretive. So the film was a play first. Everybody loved it, there was no scandal. Everybody said it was great. Even Brigitte Bardot came to see it because she was dating Sami Frey at the time, and that was before we did Bande à part. I got the Best Newcomer prize from the radio and it was really great. And then we shot the film about three years later in the South of France and we showed it and it was banned, by the Church, by André Malraux. It really became a big scandal. Nobody understood why, because of course there’s this homosexual thing going on in the story. It was totally forbidden to talk about that at the time but today everybody knows about it! Priests abuse small children all the time, all over the world. Diderot’s book was forbidden for over 150 years in France. Denis Diderot is a big classic, and this book was forbidden in every school for many years.

Godard wrote an angry letter to Malraux asking him to lift the ban…

Godard was very angry because Jacques Rivette was also one of his friends. Even though Rivette and I didn’t see each other very much, I still had a great affection for him. We did two films together, and I was very sad when he died. Rivette was a little bit like Jean-Luc, he was very reserved. He was not a big mouth, you know. He liked classical music and he kept working until he died.

Anna (Pierre Koralnik, 1976)

You also made a musical with Gainsbourg in 1967, Anna, named after you. How was it to work with that wild man compared to the quiet Rivette?

It was so great to work with Serge. We spoke slang and drank red wine and ate cheese. Gainsbourg was a real perfectionist at the time, everything had to be perfect. So he was a little bit like Jacques Rivette in that sense, but in a totally different way. He was more fun. Jacques was very methodic and mathematical. Gainsbourg was a perfectionist too but in a more funny way. He still wanted everything to be as good as possible. But nothing is perfect, it’s impossible. Even though Napoleon said everything is possible! It’s impossible to be totally perfect, because what is perfect for you is not perfect for me.

Godard always said you should have worked in Hollywood, but that Hollywood at the time was already far from its Golden Age, the kind of cinematic paradise the young filmmakers of the New Wave had dreamed of being a part of. In fact, Godard had planned a film project in the U.S. starring you and William Faulkner, but put it aside when Faulkner died. Do you have any regrets about not having been involved with Hollywood?

Yes, Godard wanted to do a project with Richard Burton and William Faulkner, and I would be a kind of maid or gardener. But that could have changed too, because you never knew what could happen with Jean-Luc! But no, I do not have any regrets. I got my best share of Hollywood from working with George Cukor on his film Justine (1969). I really loved him and we became very good friends. Every time he came to Paris, we would see each other. He would call me and send me telegrams for my birthday. It was so great! We would go out to eat and he would say, “French food is a little bit heavy. Let’s go and have a nice hamburger.” But a real steak, you know!

Cukor taught me a lot. He said to me: “Anna, you learn the lines and then you say them in a bad way, in an angry way, in a crying way, in a hysterical way, in a funny way. Then you sleep on it, and then you see, when you come to the set the next morning, you will be able to do something very interesting.” You could do this as an actor because it was very rich in your head. Jean-Luc was the same. He would say: “You actors, you don’t work enough. You have to work at least eight hours a day in front of the mirror to see if you’re good or bad, because a worker works eight hours a day!”

Yonca Talu is a filmmaker living in Paris. She grew up in Istanbul and graduated from NYU Tisch.