Interview: Amos Gitai

With each new work—fiction or documentary—Amos Gitai examines the conflicts that make up the landscape of Israel. The latest chapter from his film diary, West of the Jordan River, which premiered in the Directors’ Fortnight at Cannes, traces his return to the West Bank’s Occupied Territories and the drama of daily cohabitation. This was Gitai’s first foray back to the Territories since his controversial Field Diary (1982), made before and after Israeli intervention in Lebanon. During the shoot, he faced the wrath of his compatriots, soldiers of the Occupation who threatened to smash his camera, and at the Jerusalem Film Festival, his critique of Israeli settlers was violently decried.

Gitai, Israel’s favorite filmmaking son, wounded in the 1973 Yom Kippur War, whose Bauhaus architect father Munrio Weinraub had fled Hitler’s Germany to become a heroic figure as the designer of Haifa’s Holocaust memorial Yad Vashem, went into self-imposed exile. “The turmoil and the hostile reactions were such that I had to leave the country,” he recalled later.

The renegade filmmaker, with a PhD in architecture from Berkeley, became not so much a man without a country as a man of several countries. His new home was in France, where he worked with great directors of photography, Henri Alekan and Renato Berta and, more recently, Caroline Champetier and Eric Gautier. He dramatized antique themes of the Golem on stage with Samuel Fuller, who became Gitai’s friend, as did Jeanne Moreau, who also starred in his telefilm Plus tard tu comprendras (2009). And in the vast Boulbon quarry during the Avignon Festival in 2009, Moreau read from Flavius Joseph, the 1st-century warrior-historian who recounted the fall of Jerusalem, in Gitai’s stage production The War of the Sons of Light Against the Sons of Darkness. At the Odéon in Paris in 2010, she also did a reading of the letters of Gitai’s mother, a creative storyteller, who went to Vienna to meet Freud.

Gitai made Free Zone with Israeli Hannah Lanslo, who won Best Actress at Cannes in 2005; Israeli-American Nathalie Portman; and Israeli-Palestinian Hiam Abbass; and then Disengagement (2007) with Abbass, Moreau, and Juliette Binoche. Last summer, he staged a theatrical version of his documentary Rabin, the Last Day (2015) under the title Yitzhak Rabin: Chronicle of an Assassination Foretold at Avignon’s Palais des Papes. Another production of this piece, now called Yitzhak Rabin: Chronicle of an Assassination, will be presented at Alice Tully Hall on July 19 as part of the Lincoln Center Festival.

West of the Jordan River opens on a 35-year-old Amos, interviewing a young Rabin—an interaction whose many twists and turns have provided the inspiration for theater works and video installations. One medium is not enough for Gitai.

In his Paris apartment, Israel’s rebellious son assumes the stance of a warrior. Slouched back in his couch, he appears both on guard and guarded, a man who contains a story too tumultuous, too rich in conflict to be shared without delving into ancient memories. But this story is told and retold in myriad forms, including a massive book Amos Gitai (2016) that covers his history and his cinema. Gitai has reinvented himself once again as a chronicler, and as an artist, swinging back and forth between film and staged events, fiction and nonfiction, reacting to political issues in a white heat.

A recent Paris Match interview was titled “Amos Gitai, Peace Nostalgic.” But in fact, he isn’t nostalgic: he looks back in anger, seeking to build something new on disputed land, looking for a better story. Here is the new Gitai, eternal seeker.

We first met in Cannes on Kadosh [1999] and then on Kippur [2000], your story of surviving a helicopter crash on Yom Kippur, October 6, 1973, during the holiday that turned into the Yom Kippur War. You made this movie 20 years after the accident. Today we meet in Paris on the day following the French presidential election to talk about your latest, very political documentary. How do you feel?

Well, slightly relieved, but these politicians who set populations against each other… We have one in Israel and we’ve had him for 20 years!

Kadosh was a film about interiors like David Volach’s My Father My Lord [2007], which also takes place in a stifling Orthodox home. But you are known for your exteriors—the helicopter scenes in Kippur and movies like Free Zone, which take place outside and feature traveling shots and visits and revisits to the Territories.

I haven’t seen My Father My Lord, but I’ve heard it’s very good. Volach came from a religious family; I didn’t. It makes for big drama, the differences between people in Israel. I’m still too close to my own film [West of the Jordan River]; still too close to know really. Editing is restructuring and sometimes you only understand after, like in Jewish law: I will do and you will listen—strange! First you do, you make, then when you edit, you listen. It’s a bizarre procedure that helps keep the flow intense, with emotional sequences, like the scene with the Parent’s Circle, where women from both sides of the conflict who lost a husband, a son, meet together—a kind of fatality.

The question is, as in my interview with Charlie Rose when he asked, what does [Israel’s Prime Minister] Bibi want? I don’t know what’s next—does he want more power? Today, people are persecuted, the Culture Minister closes private galleries. Bibi will succeed in destroying, like Trump; both are so brutal and vulgar, they harm their own country. The Minister of Education closed the theater in Haifa, and now Arabic won’t be the country’s second language—it’ll only be Hebrew—that’s ghettoization.

We saw the older Rabin, and his murder in Rabin, the Last Day. Your new film opens on a young you, who has come to interview Rabin, also young and vigorous. So it’s a kind of time travel. What dictated the form?

This film is a diary, a road movie. The killing of Rabin exploded the very possibility of a certain civilization—everything was blown up in fragments—so now let’s look for the fragments. In each project, including the exhibit and the book, it’s a question of looking through a different medium at the implications of that assassination.

You go on the road, revisiting scenes that you’ve already filmed and make discoveries, like that amazing Women’s Caucus scene, in which mothers and wives, Palestinian and Israeli, come together over their dead. Is this a rare initiative?

Yes, these women take responsibility, but the lack of responsible government prevents the individual from taking responsibility. My film is the act of a citizen, and this citizen’s act is at the root of the projects I’m working on today.

You have a surprising interview with a young woman, a rare settler who is open to the Arabs’ predicament and who gets shot in the hip!

She was great, and knowing she is a settler you expect her to denounce the Arabs viciously. I was afraid my producer wanted the usual stuff—Arab terrorists and so on. Instead, I looked for the cracks in the wall and found them, which was my intention, the point of this film.

You know, I’m not a professional filmmaker, I never studied cinema, but I am an architect. And I feel very privileged; I do what I like and most of my films are inspired by some impulse.

You were friends with Sam Fuller, credited him on Kippur and cast him as Flavius Joseph on stage and in the 1996 film Metamorphosis of a Melody with Ronit Elkabetz and Hanna Schygulla. It must have been quite something to work with the man who made The Big Red One.

It was great, Sam wrote about it in his memoirs. I was living in Paris and I made Golem, the Spirit of Exile [1991] on stage with Sam. We miss Sam, and we miss Ronit, too, she was very special. I am close to Jeanne [Moreau]—she just called me right before you came—she’s an extraordinary person. I learn from all these people.

And last year at Avignon, you worked with Hiam Abbass again on the project you are presenting at Lincoln Center. You move easily between mediums, different stages. Can you talk about the process, how you go from one project to the next? Would you say that each project is motivated by your reaction to injustice? That’s what we saw from the beginning, like in Kadosh, the way the childless couple in that Orthodox neighborhood were mistreated.

Kadosh was made against the Supreme Court, these guys in religious garb who want the country to be run by the laws of the Torah and the Talmud! When you see Kadosh, you may find it’s beautiful because the scaffolding is down, and now you have the film—Kadosh, too, was despised when it was released.

We know that Guernica was painted by Picasso about the Basque village, but today we see the painting, the colors. I’m that kind of filmmaker and I think that Israelis are touching and interesting and that we deserve a strong cinema.

Golem, the Spirit of Exile

And now, once again, Rabin is at the center of your film.

It all started over 23 years ago when Arte proposed that I follow the Oslo agreements to make a documentary [Give Peace a Chance]. I went to Washington and Cairo with Rabin and saw how he tried to bring about coexistence—and as a result was killed. So let’s begin by telling the truth. You have to be honest, you can’t tell people stories.

The Arena of Murder [1996], which looks as if it had been made in a frenzy, is your first film about the assassination of Rabin. You had planned a series, starting with Parcours Politiques (Political Paths). Another was made from conversations with Emile Habibi, Amos Oz, and David Grossman—but then, on November 4, 1995, Rabin was murdered.

And now, 20 years later, we are feeling the lack of a real political figure who wants to move forward, a lack that puts the whole Israeli project in danger. Nobody is an angel in this conflict… it’s a mix of angels and bastards on both sides. So this focus on Rabin is not about a cult of personality.

When we see him in your latest, West of the Jordan River, it’s a revelation: he’s young, high energy—it’s very moving.

He was moving; he was the kind of Israeli I like, a man with a certain simplicity. Even if you disagreed with him, he was the only Israeli political figure who told the truth. He was rare.

So this is the third film you’ve made about him—if you have a hero, he’s it?

Yes.

Kippur didn’t come only from your experience of your helicopter being shot down but also from political awareness; it’s not just a war movie. You interrupted your architecture studies to fight in that war.

Yes, I made that film because of the arrogance Israelis showed their neighbors in the period leading up to the Kippur War.

And when you made House [1979], the documentary about a house that becomes haunted, occupied by different families, from the original Arab family to generations of settlers, this too came from political awareness, from stories that are both beautiful and upsetting.

I didn’t know when I made House that it would become a trilogy—and I didn’t know it would be censored by Israeli television!

How did that film take shape?

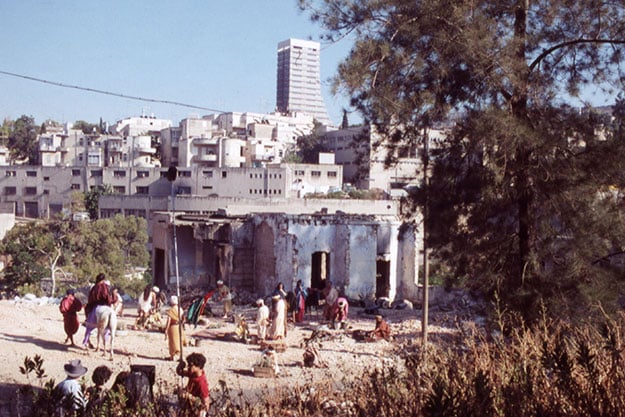

I was finishing my PhD in architecture at Berkeley and had returned to Israel. First, a Palestinian doctor owned this house in West Jerusalem until 1948. Then the government put an Algerian-Jewish couple in the house, and after the 1967 war, it became public housing. The new owner, an Israeli University professor, converted it to a villa, and brought in workers from the refugee camps.

So you have the entire history, one dwelling superimposed on another—perfect for an architect. And you went beyond architecture. How was it for you living in the midst of conflict?

I grew up with conflict; it’s not easy. It takes a lot of energy and you have to stay cool because if you enter a spiral of paranoia you destroy yourself.

You came from pioneering parents who had busy lives. How did you find your way?

I had a great mother, a great storyteller born in Tel Aviv, whose family had came from Russia in 1905. And she took me on trips. She didn’t have much money, but she took me to the King David Hotel in Jerusalem just so I could see it…

So, I had Russia, and Germany in my history with my father, an architect who had studied under Mies van der Rohe—a mix. My father having worked at the Bauhaus was great for form. It’s good for a filmmaker to inherit form.

You’ve said he didn’t have much time for you?

Yes, but there are kinds of communication that don’t require much talk. When I was 10, my father went to Japan, my mother to England, and I went to a kibbutz, so ever since, when I see a collective that leans in one direction, I go the other way.

How was the kibbutz?

Fun and torture—when you are a foreigner, it takes time. The fun part was living among nature, working in the fields.

Haifa, your birthplace, is still your home? You wrote:

“And there is also cinema

and its origins

Because I am of the Jews

Who inscribed in stone

Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image.”

Haifa is situated on Mont Carmel, where slopes are divided by valleys even more than in San Francisco. It’s not really urban, you don’t have the life of Tel Aviv, it’s much more low-key. It’s the only city where the relationship between Arabs and Jews is good.

Do you feel when you go back that you have support from your peers, from David Grossman, for instance?

We talk on Skype, yes. He said he feels that fascism is in the air, but I don’t use that term. I see a regime that is affecting education, culture, and other fields, an authoritarian regime. What can we do? We can make a film. It’s a beginning.

Grossman is a rare person.

An extraordinary person. I learn from these people. And my work, inspired by Israel, exists thanks to the French. It’s not the way it is in America. Even the talented Pedro Almodóvar gave up trying. You can make your own film, the French co-finance films from all over: Iran, the Philippines, China… And yesterday, we were delighted that they didn’t elect another crazy figure!

Sharon, Israel’s military hero ended up in a coma for eight years before dying; Rabin was murdered after a peace rally!

Jews of the diaspora, Golda Meir, Ben-Gurion, who were born in Europe, understood the fragility of Jewish existence. But after them, borders were not defined; they were elastic, too small, too big. Rabin was the only leader who sought dialogue, who sought agreement. With Sharon, there was no discussion. I prefer the Rabin way. And today, we have arrogant characters like Bibi, who have no memory of our fragility, so they are problematic. That’s where we are today.

And the Wall makes things worse?

People can’t even see each other. So there’s the impact on Israeli society and you hear things like, “Migrant workers are a cancer!” Can you imagine using such language?

And today, they are putting limitations on young filmmakers. Yet we were never disloyal, just critical. You can only be sad when this is the country you were born in.

It must be painful to be perceived as disloyal?

It is, but you have to stay lucid. If you enter a dark hole, you join the other side. You have to be optimistic, and you mustn’t be bitter about your own country because your country is the source of your inspiration. The relationship with one’s country is complex, but they don’t own you. If they start to behave as if they own you, that’s the end.

You go from documentary to fiction and back, and now your documentaries look like fiction.

Sometimes a documentary, like with Marcel Ophuls’s films, has the force of fiction.

West of the Jordan River is a French production with funding from television?

Yes, and the film will be shown in New York.

That should be interesting. Ophuls said something funny about New Yorkers’ reaction to his documentary The Troubles We’ve Seen [1994]. He said, “Ah, these New York Jews who have never gotten closer to a shtetl or a pogrom than Rumpelmayer’s and think they own the Holocaust!”

Yes, it should be interesting!

Yitzhak Rabin: Chronicle of an Assassination has its North American premiere on July 19 at Alice Tully Hall in Lincoln Center. West of the Jordan River is scheduled to open in New York on January 26 at The Quad Cinema.

Joan Dupont was a film correspondent for the International Herald Tribune and a longtime contributor to The New York Times.