Interview: Alex Ross Perry

Most of the conversations I’ve had about Golden Exits while on the ground at Sundance suggest what’s often called a “divisive” reception, which should be a recommendation—antipathy is almost always to be preferred to bland indifference. Alex Ross Perry’s fifth feature is perhaps less overtly aggro than his other output, but nevertheless vibrating with tamped-down emotions, an ensemble piece which concerns itself with the (sometimes secretive) comings-and-goings of a cast of New York thirty- and fortysomethings trying to keep their carefully curated lives together at the expense of absolute honesty.

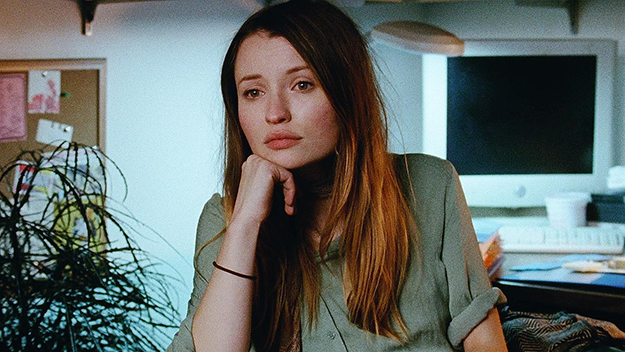

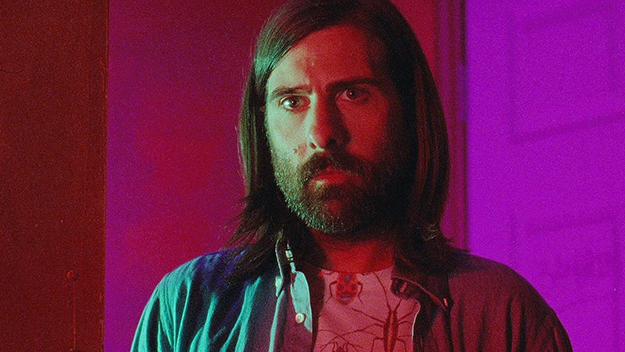

Following two-hander Queen of Earth, Golden Exits is by contrast a rather sprawling network narrative. Nick (Beastie Boy Adam Horovitz) is an archivist embarking on a project to preserve the effects of the deceased father of his wife, Alyssa (Chloë Sevigny), a project that is overseen by Alyssa’s older sister, Gwendolyn (Mary-Louise Parker). Gwendolyn manages her father’s estate with the help of her assistant, Sam (Lily Rabe), who unloads her existential angst in meetings with her sister, Jess (Analeigh Tipton), who runs a recording studio with her husband and former employer, Buddy (Jason Schwartzman). Buddy’s domestic harmony risks compromise thanks to a budding relationship with the 25-year-old daughter of one of his mother’s friends, Naomi (Emily Browning), who has arrived in New York from Australia to work as an assistant and amanuensis to Nick, who likewise feels stirrings of desire towards her—though the two men’s lives barely intersect, and they never know of their mutual infatuation.

Perry is working again with his well-established crew—cinematographer Sean Price Williams, composer Keegan DeWitt, and editor Robert Greene—while the cast is rounded out by familiar figures from the New York independent film world, including Kate Lyn Sheil, Craig Butta, and in a small role as a gormless barfly pick-up artist, Keith Poulson. Film Comment met with Perry at Park City’s Bandits Grill & Bar in order to talk shop the day after the world premiere of Golden Exits.

How did the structure come together, this network narrative idea?

For me, now, everything from Color Wheel onward is just scratching some itch that the last movie didn’t do. From that movie, where it’s two people in every single scene, I said, “I need to make a movie where characters kind of come and go.” With Listen Up Philip, you have characters drop in and out for sometimes thirty, forty minutes. After that, I said, “I want to do a movie where it’s one character in every scene,” which is Queen of Earth. After that, I said, “I want to do a movie where no one is in even half of the movie.” Even more than Listen Up Philip, where there really is no central character. I love movies like that. They’re very good when they’re done well. And it became an appropriate receptacle for where these stories were landing.

The movie started with the idea of Adam and Emily’s characters, and then I knew about wanting this Jason character, and then it was… If you give Jason and Adam each a wife, and then you kind of have this other woman who is the sister of Chloë, who is the woman that he works for, that makes sense. Now I should make a mirror on the other side, where it’s like, a triangle of a husband, wife, and sister-in-law. And now I have enough characters that I can do almost like a dollar bill narrative, where you’re passing from Person A to Person B. A lot of movies like that, at least the bigger, most famous ones—Nashville, Short Cuts, Magnolia—are usually a 48-hour time period. Which is a very comfortable framework for that. But this is about two months.

For the framework you have this archival project, and as somebody who knows a few people in archiving, these projects are very finite things where you’re scanning materials, you’re putting together whatever the narrative that is spelled out by the materials is, and then you come to a point where there’s nothing left. Eventually, you hit a wall with the material.

Yeah. Watching the movie again last night, I was reminded how much the feeling you just described, of getting to the end of something and hitting a wall, reminds me of why I wrote this movie, and how personal that aspect of it is, where you’re just like, “Yeah, I’ve been working on this for two years and now I’m done. What now?” This isn’t the end. Lifetimes packed into boxes, shipped away, and it’s like… How do you think I feel when I work on a movie for a year, and then I put it on a DCP that fits in someone’s pocket and then it’s gone? Is that what all that was for? And I was reminded, watching the movie, like, “Oh yeah, this was supposed to be really personal.” There’s a lot of my own questions, misgivings, and curiosities about the way I work and the way people like me work in what Nick is doing in this movie. I remembered that when watching with an audience. The way his despondency towards the end, about lack of emphasis, and the lack of any celebratory completion upon finishing a project, was exactly what I’m feeling when I’m watching the last scene of a movie at the world premiere. What now?

“Is that all there is?” I believe is your kicker.

Then I’ll go back home and I’ll see what else. Much like him. I’ll just go back to my desk and that will be that.

So the Nick character is the one you began with?

Him and the Naomi character. The idea of this guy as an archivist and the idea of this young girl as his assistant. Sort of classic Rohmer girl who comes to some place for some limited period of time and that’s what the movie’s about. So the two of them started, then, like I said, I was like, “Well, I know there has to be this Mary-Louise character, because that’s also part of this world.” That’s where the idea of the archiving came from, is the executor and these women and these children of these deceased people. And then it built from there, and added people where I was like, now we can pass off to spend time with these, and spend time with them.

You have these mirroring triangles and then you have your outlier, which is the Naomi character. An outlier in terms of her age, an outlier in terms of the sexual threat that she implicitly poses as someone blooming and in her full prime, and the discomfiture that is native to when you’re 35, 40 years old interfacing with somebody who is ten years younger.

It sort of happens to everybody at some point. She’s kind of a blank-ish slate in the movie. I mean, we know what her deal is, we know what she does, we know why she’s here, but she’s very mellow about her own ambitions and her own purpose. She says very early, she just finds the private lives of these people kind of compelling. She’s not forceful about it, she’s not old enough to be emotional about it. It’s just this thing that this young girl is exploring as a point of curiosity, and having her bounce back and forth between Adam and Jason, and the trickle-down effect of that. Most of her time she spends with the two men.

You spend a lot of time limning out this peculiar kind of interaction between her and these attached guys who take the matter of their fidelity seriously, but are also bending it about as far as it can go without breaking. Maybe not necessarily wanting to commit to cheating, at least not when sober, but also interested in seeing if that ability to stoke desire in another person is still there.

You see Jason getting a little puffed-up chest from the attention he’s receiving, without really bringing it in. In the first scene with them, he’s being funny, making jokes; he feels it, and is like, “I know what I am. This is my default mode of being a fun, gregarious guy. But yeah, this is having this effect that I need to keep an eye on.” And it’s stated by various people in the movie that both of them, Nick and Buddy, seem to have had various indiscretions in their past, which neither one of them brings up themselves. The Greg character, Craig Butta, screams it at Jason during the birthday party; Mary-Louise says it about Adam’s character. Which is just part of it. People try to heal and move on, and Adam and Chloë are in their forties, and Analeigh and Jason are in their thirties. And they’re both dealing with something that seems to have happened at some point in the past. And that was a conversation with both of them. How long ago did this happen? One year or five years? How was it dealt with? What is the relationship now? There’s a slipperiness to that. I think the motto of the movie and the way the characters live their lives is, “Let’s just not talk about this.”

In Listen Up and Queen of Earth, everything that the characters think is then said out loud to someone else’s face. In this movie, everyone seems to think, “Yeah, there was this affair and now he has this girl, but let’s just not talk about it. I’m sure it’s nothing and it will go away.” And then it does or it doesn’t. Emily sort of feels herself drawn towards Jason despite him not really doing much to bring her in, other than being friendly and spending all that time with her when she’s lonely. And then Adam really would love her to be looking at him in that way, but then she just never does at all. That’s a mirror element as well, of her being at the center of a triangle between those two men.

There’s a line that pops up, variations on it, a few different times in the movie. Somebody expresses a positive opinion of somebody else, and the rejoinder is, “Well, you don’t know the whole story” or “Wait until you get to know them.” That seemed to me emblematic of something that runs through the whole movie, this idea of, if you think you know something, you’re operating on insufficient information. It comes from talking about the archive, and the way that the materials don’t express the relationship that the two sisters remember between the father.

Yeah. Everyone has a different memory of your parents. Yours and your siblings’ could differ. One of the great film titles, really, of all time—you remember the Resnais movie, Private Fears in Public Places? I feel like that could be the title of so many movies. A big idea in this movie was, you put Emily in a room with Mary-Louise, Mary-Louise says, “Nick is a loser. Alyssa’s a liar.” And then Emily goes back to work, and Nick says, “I don’t listen to anything she says. The woman is a complete liar.” That is genuinely the way people talk about other people. That is 100 percent, exactly how everybody acts. Nobody doesn’t do that, except for, you know, the Pope. And no one ever lets on. And even at the end, Chloë says, “I know Gwen wanted to spend some time with her. I wonder if that ever happened?” We know it did, but she never mentioned it. No one ever mentions it.

I think that there’s something very murky about that, the private lives that people protect, and the way they want to try to put forth a certain image of themselves. Nick is just this guy on the straight and narrow who sits at his desk, Mary-Louise has it all together, and Lily is just sort of more verbal than all of them in grappling with the image that she tries to put forth, which is a very stylish, very together, cool assistant. But we see all the pain that she’s actually going through. Even though she has the fanciest clothes in the movie and the most styling, she’s clearly the one who hurts the most because she doesn’t have anything and wishes that she does. Other characters have something and are curious about why it makes them feel one way over another.

To return to the idea of the insufficient information, there’s also the fact that the event that seemed to be set up from the get-go, never happens: Adam and Jason’s characters at some point coming to an understanding that they both have been constructing a fantasy life around the same person.

Nor would it necessarily in life. That was a real editing miracle in the five takes we did of that loud, long-running party scene, the fact that the one, where it’s like a wide shot, actually in focus, and Jason just says, “What’s her name?” And no one hears him. That’s so important.

That’s a really unusual scene for the movie in that you have a lot of people clustered together. It’s almost like the sort of Ferrara shot where the camera is scanning this figural grouping, whereas a lot of the movie is basically like one-on-ones, maybe two-on-ones for the case of the two sisters.

We brought a lot of people in there. I mean, the scene had to feel cacophonous enough that what the Nick character does in the next scene makes sense. It had to, like a carbonated bottle, shake him up enough that when he leaves the bar, he just pops. It’s not a long scene; it’s under four minutes and it’s entirely blocked-off, tripod stuff. Just a lot of yelling and a lot of pumping men up, men just getting really mad. You cut into that scene from the quietest scene in the movie, where we took even the ambient noise out, with Chloë and Mary-Louise, where Chloë is home, having wine, dead quiet. We cut to Lily and Analeigh, the other set of sisters, different home, very quiet. And then just men screaming. Men just being lewd and vulgar and gross and miserable and talking about cheating on their wives and talking about all these great women that they’ve been with in the past, and then it just makes him be like, “Okay, I don’t want to be a loser.” After we’ve heard a character repeatedly refer to him as a loser up until that point.

When you’re looking at a movie that is a lot of one-on-one conversation, what are some of the ways that you address making that not monotonous, giving every scene a different tonal value and creating distinct identities for every one of these?

It’s tough. It’s so much about interior spaces and so few exteriors. You’re in the archiving office a lot, you’re at Adam and Chloë’s home, which is huge and feels so empty, and you’re at Jason and Analeigh’s home which feels very cramped and normal, and you’re at Mary-Louise’s home which feels even emptier. We shot this movie in wider shots than I’d ever shot anything before. At Mary-Louise’s house, you’re in this wide shot where you can practically see her head to toe for, like, 60 seconds. I’d never done anything like that. It’s just about the people in these spaces; it’s just about Nick in his office, and, to a lesser extent, Chloë in her office. And to a larger extent, Mary-Louise in her home, and Jason and Analeigh in their studio.

It’s just about these people in these spaces. It’s like a Paul Schrader thing, the man in the room. Whatever is the space that defines the human is a spiritual place for him. The room that the person spends their life in defines them, or they enter into a room at some point which defines them. This movie is very much inspired by that impetus as well. I mean, that’s me. I live at home, as most people do, and I work at home, and I don’t leave very often. If I do, I just go for a walk around, like Adam’s character does in the movie. I’m very defined by my space and my home. I don’t let people into it. I don’t leave unless I have to. The movie’s very honest to my life in the sense that it all takes place in my neighborhood. The only time that I leave Brooklyn is to go to Anthology. That’s it. That’s autobiographical.

It’s still a movie that’s very heavy-duty on close-ups, some very tight close-ups.

That’s always something that I’m drawn towards. I wouldn’t put actors in a movie if I wasn’t interested in seeing their face from six inches away on a movie screen. But yeah, the wider stuff, I just wanted to try it. When you’re in a wide shot for three minutes and suddenly you’re in a real close-up, you’re just by instinct saying, “Oh, there’s something narratively happening here that justifies that happening,” rather than just an entire scene of close-up coverage. That was kind of the idea, to make sure people felt those cuts and saw them, and processed the cut to a close-up very specifically.

Early on there’s a shot that almost looks like a split diopter shot.

That was a split diopter shot. We used a lot of that in Queen of Earth. I love it. We got it again, just because we got the same equipment list that we got from Queen of Earth. The split diopter was in there, we tried to use it. A domestic drama doesn’t necessarily need a split diopter, but we got it in there once. It was out of the edit for a while and then it came back in, because there was a dolly shot to cut to from that, and for a while we had dolly and split diopter. Then we said, it’s going to have to be one or the other of these two shots. And the dolly seemed too much, like we were trying to say, this is a big moment in the movie.

Talking about the desire to look at people from six inches off, I’d be interested to hear a little bit about how Adam Horovitz got in the mix, because he’s not acted in anything outside of While We’re Young, right?

He’s actually in one scene of another movie here, called Roxanne Roxanne. Didn’t even know that until I saw an interview with him and he was like, “I’ve got this other movie here.”

Sounds exactly like a Seinfeld movie.

Roxanne Roxanne. Rochelle, Rochelle. It’s actually based on a rapper from the ’80s, a true story. I mean, so many of the characters in the movie are right in the demographic of actors that I’d either worked with before, or the actors that I’d met with on projects that I would like to work with that I’d not yet been able to. Jason, Analeigh, Emily, and Chloë are all people I’d been in touch with—obviously I’d made a movie with Jason—or had met with, just to talk about other projects that did or didn’t happen. So that’s a demographic I had written for a lot. Then I was like, “I just want to make a movie about a slightly older man, like forties or fifties, but like an intelligent-seeming dude, not like a guy that kind of seems like he should be the uncle on a sitcom, the guy that you actually believe in the world of this movie.” So you get the list from the agency, and it’s like, we need New York actors; we’re not flying anyone in. We need a man who’s in his forties or fifties, who can be married to Chloë, who’s already attached. And he has to be available and willing to do a low-budget movie. And they sent me some people, and I saw Adam on it, and I was like, 100 percent, yes. Everyone else on it was names you would expect, kind of like New York theater type guys that are also very good actors. And then him, I was just like, yeah, that’s it. I mean, I loved him in While We’re Young, this would be perfect. This is the kind of guy that I need in the movie. And I would be really excited to work with him.

I know he’s not really an actor, but he’s a performer; he’s been performing for longer than anyone in this movie has been acting. So if he will do it, yes, that’s it. And I met with him, and I was just like, I want to tell him that if he will do it, I want him. And his agents were like, “Yeah! E-mail him.” And I did, and he said yes. I don’t know if this is entirely relevant to you, but we were just doing a panel, and I remember Jason mentioning this last night—the way he holds a microphone, it’s just like the only way to hold a microphone at a Q&A and look cool. [Picks up rolled tableware to demonstrate]

So he’s still got it.

He just can’t not be cool. We had to cut one shot in the movie because he was walking too cool. It was a shot that, previously, you see him walk in and sit down somewhere. We had to cut into the scene where he’s already seated. He’s a very good actor and a very interesting performer, but there’s just some parts of him that can’t not be cool.

In terms of prop usage, the glasses he wears at the office are fantastic.

That was his idea. He says he’s not an actor, but brings an idea like that into the character and is deciding when they go on and off. It makes such a difference watching him do that, and he just latched onto that as this important thing.

This film circles back to something that was central in Listen Up Philip, which is thinking about solitude as a lifestyle choice, and bargaining with solitude. People figuring out how much of it they need, the degree to which that can be integrated into a coupledom. That seems to be something that’s very close to you.

For better or worse. Basically, my existential quandary every day. That’s the Schrader thing again—movies grappling with solitude. That’s what he’s done thirty times. It just speaks to me, I don’t know. I’m not an exceptionally lonely person but I do lead a very small life, kind of by design. I’m not lost and sad; I’m very happy when I’m in my home, and very happy on the nights where I don’t go out and cook a meal and watch a movie at home. It’s a perfectly adequate lifestyle for me and I really don’t want anything else. In this movie, a lot of people have that, and someone says, “Do you want anything else?” and they say, “No.” Obviously, they’re like, “At this point, I don’t know. It’s been ten years of this. Maybe I do.” That’s been very personal to me. I find a lot of tranquility in the lifestyle I’ve had for the last two years, which is basically I write at home at my desk five days a week as a job. I start my work every day at around the same time, and I have a routine as though I had a job. Which I do, I just don’t have to go anywhere other than my desk to do it. It’s always something I was interested in; now that I really live it, I wonder if I’ll get tired of it. Two years in of just 11 a.m. to 6 p.m., writing and being on the phone and doing errands. It’s still kind of nice, and I still find it to be very enriching.

Doing this movie, we shot on a very manageable schedule, 9 to 9 every day. 8 to 8. Everyone was so happy. Everyone on the crew was like, “This is great, I can go home, I can see friends, I can go out, I can have dinner, I can actually see my girlfriend, see my whatever.” And Sean was miserable. Because every day, the day is over, he goes home and there’s nothing to do. All day one day, he was talking about some movie he had to go see. Dying to see. Couldn’t find anyone to go with him—didn’t go. And I was like, the more important a movie is to me, the less likely I am to try and get anyone else to see it. I love seeing movies alone, and I just really need that. It’s being alone, but it’s not being lonely. The movie asks about that. Because I don’t understand that. If I had the answer, I would have everything in my life figured out. But I just like sitting at home, by myself, or with [my partner] Anna, and I’m just very happy doing that. For Christmas, I’ve been working so much finishing this movie, everyone in the industry that I have any reason to interact with went on vacation on whatever day Rogue One opened. The 15th or something. And I had to do post until the 23rd. I was just stuck in this grind, and then starting on the 23rd, when I got home, I didn’t leave my neighborhood for like two and a half weeks. I sat at home every day reading Stephen King, watching screeners.

A lot of this is very close to Adam’s character in the film. But a big part of the movie is the discordance between the official version that people are giving of themselves, like Nick. He’s emphatic about the pleasure of a life that fits into these few city blocks, where everything is regimented up to the very finest detail, but at the same time, when we’re encountering this character, there is some disconnect between the self-presentation of having everything figured out and this desire—a very key word in the movie—which does not fit into that rubric at all.

Perhaps. In the parallels and mirrors we were talking about, a big thing that Jason said was important for him to understand about his character was how we see Jason’s character out a lot. At some point, he just said, “Does this guy go out every night no matter what his wife is doing?” And I was like, “Yeah, he goes out every night. Maybe just for a beer. But every night this guy has to just pop out for a little bit and walk around and have a drink and meet up with somebody just because he wants to. But this is that guy.” I don’t understand that guy at all. I can’t imagine living like that. I’d just be so tired all the time and spend so much money. But I was like, that’s this guy. And that’s the opposite of what Adam is doing. Like you said, there’s the official version, and then there’s the other thing that, in the span of this movie, you see nag at people. Which I like. I like watching it nag at people. It’s more interesting to see something nag at them for the sake of this story than it is to see them rage against it, as in the case of Philip and Queen of Earth.

I wonder if you could talk a little bit about the score, which is very strong. It has this insinuating quality that communicates an enormous amount of feeling that is not necessarily the stuff that the characters are being forthright about. This tamped-down longing comes through very strongly there. There’s I think some distinct movements that it goes through, the score evolves and changes as the film rolls along.

Working with Keegan now for the third time, as with Queen of Earth, he’s reading a script, he’s watching dailies, and we have music by the last day of the shoot, which is very helpful. So the one direction I really gave him, I said a lot of this movie is people not saying what they are feeling, and it should be really clear to the audience because of what we’ve seen from the characters. But the music should express what they’re feeling. So if it’s clear that someone’s really hurting, and may want their loved one to ask them about it, and the scene doesn’t contain that, the music should really underscore something that’s not in the movie. The other thing that we played with and abandoned, which I do want to do but it’s very tricky, is having themes. I wanted the music to be like, this is Nick’s theme, this is Naomi’s theme, this is Buddy’s theme. It became much more of a continuum rather than this sort of like, Star Wars, Lord of the Rings-type thing, where when someone talks about the Empire and you just hear the tones of the “Imperial March.” You’re with the rebels, and you hear the Empire music, and you’re just like, “That makes sense.” I wanted that, where someone’s talking about this character and you hear this motif about them, and you’re just like, you feel it. It just didn’t really land in the movie. So that’s an idea we have to come back to someday. It’s very tricky, at least in a dialogue-driven movie, to get away with that.

It might be fair to say that one of the subjects of the movie is monogamy being bent as far as it can go without snapping. Other than perhaps in the scene where Adam drunkenly wanders up to the apartment, nobody really heavily oversteps any bounds here, it’s more a matter of these very small, death-by-a-thousand-cuts deceits, this saying you’re doing something when you’re not precisely doing that, misrepresenting your activity. And the degree to which these characters can do that and be comfortable with it, and how far they can go and be comfortable with it.

Yeah. That’s kind of the Rohmer influence again—where the cracks are. Can Jason say, “Yeah, sorry I’ve been out till one in the morning. I was with that girl at the bar.” Of course he can’t say that. Did he do anything that he should be apologizing for? No. He didn’t, really. In fact, he sort of eventually comes to terms with what he’s doing. But you just don’t want to have that kind of conversation. So that’s why so much of the movie is just, let’s not talk about this.

How do we expedite these domestic situations?

I just like that slipperiness. I think people do it, both personally and professionally. I can’t even tell you how many times I’m supposed to be on some sort of phone call, and I’m like, “I wish I could, but I have this thing at the same time.” I’m just going to a movie. Someone in LA is like, “Can we talk at 8 p.m. New York time?” That’s end of day for us. I’m seeing a movie, and I’m like, “I’m sorry, that’s completely impossible. I can’t do it.” Which is the same kind of thing. Of course I could, and I’m definitely lying, but it’s a victimless crime. A lot of the movie, a lot of the lines are very victimless, except you do see that eventually these people do become victims because of the weight of a hundred of these little white lies. I’m just interested in that. There’s something fascinating about the idea of white lies, more than there is about the idea of huge, sweeping deceits. And there’s so much in the movie where, it’s not even lies, but people are just like, “You don’t talk about this at all.” And Chloë is like, “You don’t talk about her anymore.” And he’s like, “What is there to say?” And sort of doesn’t mention her. No one does. Everyone’s thinking about the same people, but no one’s talking to or about them. I think that’s kind of how I see a lot of interactions with people. I always am afraid that I’m being talked about when I’m being talked to.

Another big thing in the movie is this thing of people using other people as something to measure themselves against—particularly in the sibling relationships, the idea of the sibling as almost like this yardstick, or something that you use as a point of comparison. Or the Lily Rabe character, this personal assistant haunted by the idea that her employer is this possible fun house mirror reflection of what she thinks she may be 15 years in the future. It seems for a lot of the characters, talking about and thinking about other people is a way of measuring themselves and measuring their own insecurities about where they are and where they would like to be.

Sure. I think people definitely do that. Everyone does. I mean, being here at a festival is a perfect opportunity to talk about, “Oh, this person has this and I don’t.” People are very susceptible to that. I’m very curious about that. I think I was realizing, talking to people last night after the premiere about like, “Oh, it’s crazy, you’ve come so far from Listen Up Philip and Color Wheel.” And it’s like, yeah, I think the difference is just like emotionally, I eventually rounded a corner where I stopped constantly negatively comparing myself to people above me and started always positively comparing myself to people below me. Which makes me feel great all the time. And almost anyone can do that unless you’re absolutely at the bottom. Really, no one in this movie does that. I think, had that been pointed out to me prior to writing it, I would have alluded to that somehow.

You don’t get the sense that Jason’s character looks at anyone else and wishes he had what they someone else has. He just maybe wishes he wasn’t married sometimes when he’s had three beers and is at a bar with a cute girl. But he doesn’t wish he was more successful, or wish he was more free in his life, because he can do whatever he wants. He’s got a great wife. He’s out at the bar every night with someone else. He’s obviously just lying about where he is. So whose life would that guy prefer? He’s pretty much got most people’s idea of total freedom and whatnot. Comparing people to each other, and in a movie with two sets of parallels, two couples with two unmarried sisters on either side, it’s like, everyone’s got something that seems fine. You see this woman in her big, nice brownstone in Brooklyn, and she’s rich enough to have an assistant, that sounds really nice. I’d like to live in that house, but she seems kind of miserable. Maybe I shouldn’t live in that house. I should stay at my smaller apartment and not be miserable.

Nick Pinkerton is a regular contributor to Film Comment and a member of the New York Film Critics Circle.