Interview: Adam McKay

Last month, the man who had Will Ferrell plop his nutsack on a drum set in Step Brothers was nominated for a Best Director Academy Award for The Big Short, an adaptation of Michael Lewis’s chronicle of financial meltdown. What looks like an unlikely path to respectability for writer-director Adam McKay is actually a logical extension of his subversive talents. McKay has always been smart about being dumb, ever since co-founding the improvisational comedy troupe Upright Citizens Brigade, right on through his sneakily satiric features with Ferrell. And what could be dumber—and more ripe for subversive scrutiny—than the market-bubble demolition of the U.S. economic infrastructure?

FILM COMMENT spoke with McKay about The Big Short, his early years in improvisation, the aesthetics of comedy, and his bizarre podcast that never found an audience.

The Big Short is your most explicitly political film, but those elements have been in your work from the beginning, and I was curious what political material you did in your improv days. I read a story that you staged a revolution in the streets at one point.

Funny, I was just telling that story to someone. Yeah, we were with our group the Upright Citizens Brigade in Chicago, when we were just starting out, working out of coffee shops and small theaters. And we used to do a bit every night: it would start as a community/town-hall meeting about putting up a stop sign, and would quickly elevate into a full-on revolution, where we would hand out tiki torches and plastic guns. (By the way, this was a different era, back in ’90—we wouldn’t do the plastic guns now.) And we would lead the audience out into the streets to go and take over this congressman’s office, this guy Dan Rostenkowski, famous for being corrupt in Chicago. And then every night I would be driving around the corner, and Horatio Sanz was the guy leading the revolution, and I was supposed to hit him with my car. And he would kind of lean in to my car as I slowed down, and one night I came around the corner and he was being arrested, and by actual cops. I have videotape of it, and he doesn’t break character, he yells to this giant crowd, “Fight the power!” and the crowd cheers with tiki torches. It was pretty crazy.

How much of an influence was Del Close on performances like this?

Del Close was the improv comedy guru (both writing and acting) in Chicago when I went there. And he was the reason I went there. I was told about this guy doing groundbreaking work, where you are improvising plays, and he could teach you how to improvise scenes. He was a big influence on my life. I worked with him for a long time. Our improv group became an experimental group. He’d work out forms with us—Ian Roberts, Matt Besser, Rachel Dratch was in the group for a while, Neil Flynn, Miles Stroth. He would use us as his group, and what he taught, looking back on it, a lot of it was about writing. He had certain kinds of things he would push, like: always look for your third thought. Your first instinctual thought was a commonplace one, your second one was kind of respectable, but it was the third one where it got special. So he would have us stand on stage until we found that third thought, and eventually we got pretty fast at it.

He taught us a lot of things. He was a big believer in always playing at the top of your intelligence—even if you’re being dumb, be brilliantly dumb. And if you’re playing a kid, don’t play a kid as dumb, kids are smart. If you’re playing someone drunk, usually if someone’s drunk they’re trying to act like they’re not drunk. Don’t play them drunk. A lot of his work was about finding a more original choice. And he did a lot of game theory for creating scenes, and finding out what the scene is about. A really formative time of my life. And at that time—this was pre-Internet—there was just this crazy migration of talented people into Chicago. A list of like one hundred people that are still writing, directing, and acting now. All the way from Tina Fey to Mike Myers to Chris Farley to Dave Koechner, and on and on. Rachel Dratch, Jon Glaser. It was an incredible time to be in that city.

I’m curious how this training, which you brought through clearly in your comedy work, was applied to The Big Short, which is more of a scripted enterprise.

The thing that really helped me initially, especially when I went to Saturday Night Live, was, by the time I got there, I had improvised, written, hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of sketches. And we had starting doing a form called “The Movie”—basically, we would just improvise a movie. So out of that we started getting the structure of scripts and how to tell stories, different kinds of stories. All of that work really pointed in one direction, which was being very comfortable with ensemble work. It became the place I felt most at home.

So in the case of The Big Short, it’s a very ensemble-driven movie, and there’s a lot of juggling of different stories and ideas. And I would give a lot of credit to that training as far as making me feel comfortable with it. I was also an English major in college, and wrote a lot of fiction, and screenplays. I would constantly watch movies. So I’m sure a lot came from that as well. But definitely that emphasis on ensemble in Chicago is a big plus for all the movies I’ve done, the more absurdist comedies and The Big Short, which is obviously a little more grounded, a little more dramatic.

How did you alter your style moving from the absurdist comedies to The Big Short? You are working with DP Barry Ackroyd here, with more handheld and a catch-as-catch-can feel. In a recent conversation with Paul Thomas Anderson, you mention how comedies are traditionally shot with stable frames, centering the performer, while in The Big Short you get big laughs with a more mobile, on-the-fly camera.

I think every story, every movie, has a way that it needs to be told. I’m a believer in form-follows-function. And in the case of this story, I really felt that this was the opposite story of Margin Call and Wall Street, which are more about the power side of the story. These are more the anxiety-ridden, pit-stained, nervous guys that were on the fringe. So I always knew that I wanted to shoot this thing in a more vérité, Costa-Gavras kind of style. I watched a lot of his movies. And when you start talking about that as a visual style, there’s one name you come to which is Barry Ackroyd, one of the great living DPs. We don’t want to be stuck with a bunch of stagnant medium shots of people on phones—we wanted to go inside these moments, feel these guys’ uncertainty, anxiety, excitement.

The part that surprised me was that usually in comedy you’re told you have to keep your frame fairly stagnant to let the actor and the ideas play the comedy, and not the frame. And I was excited to see in this movie that even though we have that vérité style, we’re still getting very big laughs—which really made me think that audiences are becoming very sophisticated very fast when it comes to visual styles.

Do you think this is a style you will carry forward into your more broadly comedic films?

Yeah, I definitely do. I’m actually really excited about it. I obviously love working with Will [Ferrell] and I’ll be doing more movies with him—but next time I do one with him I want to shoot it like this. I really think it can work. And I think it brings an energy to the movie. I knew The Big Short was going to be sometimes funny, I was just surprised by how little of a problem the audience had digging into those funny moments. We had kind of done it on Step Brothers: I talked with Oliver Wood [the DP], and we had handheld, but it was kind of minimal. With this movie, obviously, we let it fly. So yeah, I definitely think I would do it with a comedy comedy.

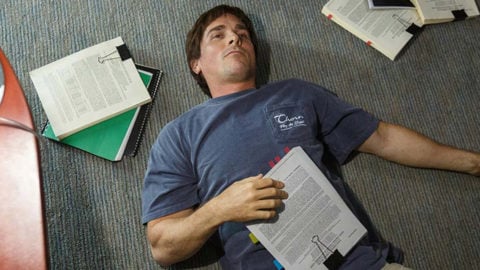

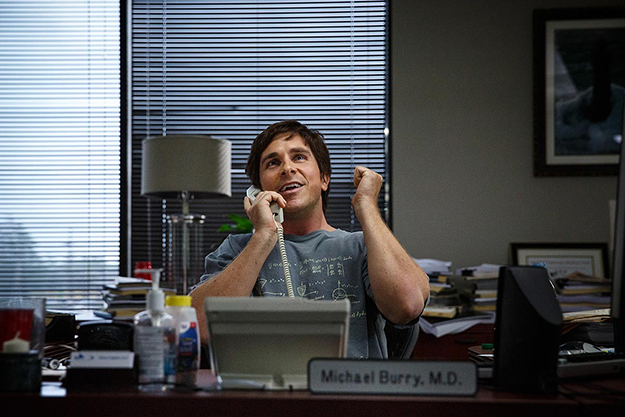

I’d like to talk about the performances in The Big Short, because they cover a range of styles. Steve Carell is tightly wound, Christian Bale is very mannered, Ryan Gosling is over the top, almost as if he’d come out of the Anchorman news team.

You know, it’s funny… If you met all the real people—which I did, I had dinner with each of them—you would go: “Oh yeah, they’re all spot-on.” They’re all different characters, interesting characters in their own right, and most of the actors used the real person as their model. I think Gosling had more freedom, because he lived inside and outside of the movie as the narrator and a character. But in the case of Bale [as Dr. Burry], he’s really drawing a lot from the real guy, and so was Carell [as Mark Baum]. Finn Wittrock and John Magaro I think are drawing a lot from the real guys. Jeremy Strong, without a doubt he is. I let Rafe Spall and Hamish Linklater have a little more leeway with their guys because I needed a certain dynamic there for those scenes to work. But what’s so great about it, and one of the reasons I love the book, is that you have these different tones and these different characters. And it allows for gears to shift throughout the movie, from contemplative, living-inside-his-head Dr. Burry, to Mark Baum, aka Steve Eisman, telling everyone they’re an idiot, and screaming at the world. Those layers of tones made that book stand out for me, so I wanted to capture that with the movie.

You mentioned that Gosling is both outside and inside the film. One of the interesting things about the film is how often it tries to pull you out of the narrative. A character will say an event didn’t actually happen. Usually in a docudrama it’s about guiding you along and being inside, but here you are continually pushing the viewer outside to be skeptical of things that are happening. Is that something your were thinking about while constructing the script with Charles Randolph?

That’s exactly what we were doing. The whole idea was that we wanted this to be a movie that was going to pull back the curtain on finance at Wall Street more aggressively than other movies had, although certainly other movies have done a great job of it. We wanted to get beyond any kind of hype or PR or bullshit whatsoever, because banks spend a lot of money portraying themselves as these stable, wise institutions. And so we were going to strip all that away and create a level of intimacy and honesty with the audience where, even if the script needed to collapse two events, we were going to let the audience know that it was happening.

Were the celebrity explanations in the script from the beginning of the process?

Oh, yeah. That was the very first idea I had when I read the book: you’ve got to break the fourth wall in this movie. And we all know the number-one rule of filmmaking is show, don’t tell. But in this case, you have to do it. I’d seen some movies do it really well, and certainly from my theater background I’d done it a bunch. So I knew it could work—it’s all about how much you do it, the way you do it. But yeah, the very first idea I had was going to those explanations. It developed into pop, iconic characters as I kept writing it. I wanted to riff on celebrity culture and how much room that takes up in our minds living in America, and how we missed this giant bubble that, looking back on it, was so obvious. But I always knew I was going to break the fourth wall and talk to the audience.

Did you have some celebrities in mind for these sequences that did not end up in the film?

The ones we have in there are mostly first choices. The only one that wasn’t was: I had just lazily written in the script Jay Z and Beyoncé, for the last one about synthetic CDOs. Right away everyone started telling me there’s no way that’s gonna happen. By that time we already had our dream cast, we had all these wonderful people, so I was like, that’s OK if it doesn’t happen, I can in no way complain at this point. So then we thought, wouldn’t it be funny to do a high-low thing, where you have a serious economist and then Selena Gomez. Once we had that idea I think I ended up actually liking it better.

That’s probably my favorite one. But I’ve heard people say that they’ve found those sequences to be condescending, implying the viewer is not smart enough to understand otherwise.

If anyone were to find them condescending, it certainly wasn’t me being condescending, because I didn’t understand it—that’s why I put them in. I had to research and learn this stuff. And I think you can pretty safely say, if you were going to run a quick Gallup poll, that probably 98 percent of Americans don’t understand it. So if there is someone in the audience who does understand it, God bless ’em, they have every right to say those are condescending. It hasn’t been the way I’ve seen it play. Every time we’ve tested it, every screening I’ve been to, the audience has been very happy.

And, you know, we’re telling them pretty sophisticated things. If we were really to condescend to them, we would have avoided the subject altogether and just said: “Some bad stuff happened.” We also knew with this movie that we were trying some stuff a little out of the ordinary, stuff that some people wouldn’t like. I’ve heard complaints about breaking the fourth wall, some people don’t like the Aykroyd style. Not everyone’s gonna like everything. But I was quite delighted with the way it ended up playing. Condescension was the last thing on our mind.

I was surprised how much I learned coming out of the film, about how all these financial tools worked, which I was not expecting going in.

Yeah, that’s how I felt about the book, and then obviously did research on top of it. The more research I did, I found out that this is pretty typical of boom-and-bust cycles: you see this crazy complexity of financial products that goes on, deregulation mixed with irrational exuberance. This pattern is repeated over and over again. And that’s exactly what happened here with all these derivatives. They created these complexities that were so complex they bought into their own scam and ended up taking themselves down. I didn’t know either, before I read it. But it was one of the reasons the book was so exciting, and the characters were so amazing.

How familiar were you with all of this before reading the book and researching the film?

I had a very rough shape idea of it—I had done some reading for The Other Guys, so I knew there was a housing bubble, and that these products had been made that amplified it. That’s all I knew. And then in reading the book, it got very specific about the products and the fraud behind them, and all the different levels of failure, the regulatory arms. Basically how the banks had captured the media, they captured the regulatory arms, they captured themselves. And that was the part that really surprised me: how giant the power and reach the banks had become. The biggest number that really knocked me out of my chair was that in the 1970s, banking was six percent of GDP and now it’s 24 percent. I remember reading that and going, how in God’s name was that never on the news? That it had become such a leviathan was a bit terrifying, when I came across that number.

You mentioned The Other Guys—the closing credits of that movie almost act as a preview of The Big Short.

Yeah, I don’t think we quite had the focus we ended up getting in The Big Short. But we talked about Ponzi schemes, we talked about the bank bailout, and how the top one percent benefited from it. I was very happy with those end credits. But then later, when I really dialed in on this one, it became very simple the further I looked into it.

Could you talk a bit about the editor, Hank Corwin, who’d worked on Natural Born Killers, JFK, The New World? I’m curious how the photo montages came together, which pull back and give you a wider context.

I can’t rave about Hank Corwin enough. The guy is just an inspired person. I had these ideas of showing snippets of popular culture, to see where Americans’ minds were at during this time, so there was some of that in the script. And he just took it and ran with it. So what was originally in the script a video of Ludacris playing on a monitor as you walked into a building, became a full on video intruding on the movie, with different snippets of stuff. Hank’s great at taking the spirit of what you have and going too far with it. So he and I had just the most fun back-and-forth collaboration with this.

The really brilliant idea was when I was trying to find a way to show the effects of this collapse. It’s such a big story you can only tell it through so many directions. We were in the offices and banks a lot, and so out of those snippets of video came the idea to use still photographs—just quick blips of people’s furniture on the street, people being tossed out of their homes and tent villages. And when we landed upon that, it was a major breakthrough. Hank and Barry Aykroyd were so essential to the fiber of this movie, and thank God I found them, because it had to be told in this style.

I’m going to veer away from the movie just to say I’m hoping somewhere down the line we get an update on how TJ. is doing. Because the “Owen and TJ Read the News” podcast was a great pleasure to me for a while. [In which Adam McKay plays TJ, a young North Florida delinquent who derails Owen Burke’s attempts to recap the day’s events.]

[Laughs]

https://soundcloud.com/owen-tj-read-the-news/new-posse

We need an update on TJ’s Jacksonville adventures.

You are without exaggeration the only person who has ever said that to me in my entire life. I didn’t know anyone listened to that. We did it, and it was so strange and bizarre.

It just seemed like you two were enjoying pushing things as far as possible, from TJ’s increasingly masochistic relationship with his stepmother’s boyfriend [Rob Riggle] to his stint in Florida State prison drinking toilet wine. Me and a few of my friends are huge fans.

Are you really? OK, I’ve got to tell Owen Burke that. We were having a blast—I was just wondering if the audience was. That’s fantastic.

Well, if you don’t mind doing another one for an audience of three—go for it.

You may have just got another episode of “Owen and T.J. Read the News.” I will tell Owen Burke this and we will do one. All right, that’s a done deal. Maybe T.J. will die. It’ll be our last one: I’ll die on the air.

R. Emmet Sweeney is a regular contributor to FILM COMMENT. He also writes a weekly column for Movie Morlocks, the official blog of Turner Classic Movies, and produces DVDs and Blu-rays for Kino Lorber.