The Man Who Knew Everybody

This article appeared in the June 22, 2023 edition of The Film Comment Letter, our free weekly newsletter featuring original film criticism and writing. Sign up for the Letter here.

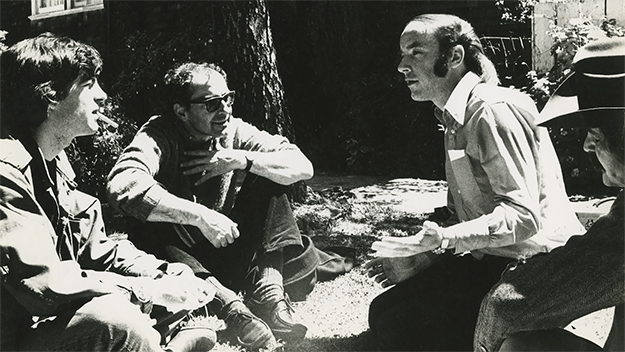

Tom Luddy (second from right) with Jean-Pierre Gorin and Jean-Luc Godard during their visit to the PFA in the 1970s. Courtesy of the University of California Berkeley, Berkeley Art Museum & Pacific Film Archive, Film Library & Study Center

At a Q&A between screenings of Breathless (1983) and The Big Easy (1986) last summer at the New Beverly Cinema in Los Angeles, director Jim McBride recounted how he got permission from Jean-Luc Godard for his Richard Gere–starring remake: “I knew this guy named Tom Luddy, who ran the Pacific Film Archive. I was visiting him and I mentioned this idea [to remake Breathless] to him . . . This was the guy, by the way, who knew everybody and knew everybody’s phone number, and anyway, he picked up his phone and dialed Jean-Luc Godard and handed me the phone.” This is often the first thing that those who knew Tom Luddy, the longtime Bay Area film programmer and producer who died this February at 79, say of him: he seemed to know everybody. His obituary in The New York Times describes him as a “human switchboard,” an apt metaphor for a man who counted among his personal contacts the likes of Francis Ford Coppola, Salman Rushdie, Alice Waters, and Ousmane Sembène—and who, across a six-decade career, introduced American audiences to numerous far-flung directors, from Werner Herzog to Larisa Shepitko.

Luddy earned his reputation early in life. After arriving in Berkeley from New York in 1962, originally to study physics, he developed a passion for film under Albert Johnson, a UC professor who programmed the Arts and Lectures series on campus and co-edited the journal Film Quarterly. Under Johnson’s wing, Luddy began his own film society (named after F.W. Murnau), assisted with others, and also wrote program notes for the Berkeley Cinema Guild, where another major figure of the era, Pauline Kael, had gotten her start. Shaped by his experience in the Free Speech Movement at Berkeley, Luddy presented Godard’s La Chinoise (1967), with the director present, at the new Pacific Film Archive in early 1968—the start of a long and fruitful relationship between the programmer and the filmmaker. Later that year, Luddy became general manager and program director of the short-lived Telegraph Repertory Cinema, a two-screen theater alternating between screenings of old Hollywood silents and contemporary art films. “Our purpose is to show films that are not shown by commercial theaters,” he told The San Francisco Chronicle in 1970. “There are hundreds and hundreds of films of definite interest to students of film that don’t get shown because they’re hard to find.” These principles would come to define Luddy’s career, as he sought to elevate work languishing in the shadow of commercial production.

This half-decade of independent programming culminated when Luddy was hired as program director for the Pacific Film Archive in May 1972. Originally founded in 1967 by Sheldon Renan within the existing Berkeley Art Museum, the PFA (formally known as BAMPFA since 1996) soon became, under Luddy’s direction, one of the preeminent cinematheques in the United States. A fixture of his programming was his eclectic enthusiasm for discovery: in a given week, audiences could see an early Soviet silent from an unknown director on Sunday, a William Wyler literary adaptation on Monday, the new Truffaut film on Tuesday, and a program of experimental shorts by the Kuchar brothers on Wednesday. As often as possible, Luddy invited filmmakers to introduce their films in person. (Many of these recordings are now available for listening on archive.org.) Modeling itself on the Cinémathèque Française in Paris, PFA quickly accumulated an enormous collection of close to 4,000 titles by the end of its first decade, including a large selection of Japanese, Chinese, and Soviet films, many of which were acquired after painstakingly searching Bay Area venues for prints. For Luddy, it was important that the repository live up to its name: the Pacific Film Archive. As he noted in a 1978 interview with Cahiers du cinéma co-editor-in-chief Serge Toubiana, “There are hundreds of thousands of Japanese and Chinese Americans here [in the Bay] and we decided to try and collect films from both cultures.” In 1998, Susan Sontag named BAMPFA the greatest cinematheque in the United States, citing Luddy’s efforts as key to its success—a claim few would dispute.

After nearly a decade at PFA, Luddy left the institution in 1980, citing burnout. Yet his talent for connecting filmmakers around the world came in handy when he joined Francis Ford Coppola’s production company, Zoetrope Studios, as a producer that same year. Luddy worked on numerous major projects at Zoetrope, among them Akira Kurosawa’s Kagemusha (1980), for which he helped to secure financing, and the restoration of Abel Gance’s Napoleon (1927), which he oversaw. His work with Godard merits special attention: Luddy spearheaded Every Man for Himself (1980) and Passion (1982) at Zoetrope, and was set to produce The Story, an epic about mobster Bugsy Siegel that would have been Godard’s follow-up to Passion. Though that project fell through in its early stages, its collapse inspired King Lear (1987), a turning point in Godard’s career. Luddy worked closely with the filmmaker throughout the production, securing actors and funding, and even introduced him to the film’s eventual star, theater director Peter Sellars. Luddy’s voice can be heard speaking to Godard and producer Menahem Golan over the phone in the opening sequence of the film.

Accounts of ’60s film culture often focus on pioneering filmmakers and film critics. Film programming rarely gets its proper place in the story, with Cinémathèque Française director and tastemaker Henri Langlois being the one exception. Luddy never published any criticism, but his influence on Bay Area and American film culture is equal to that of any of the great critics or directors of that generation. In addition to his local programming in Berkeley, he co-founded the nonprofit Telluride Film Festival in 1974, for which he served as artistic director until his death. In a profile published in the December 1978 issue of Cahiers du cinéma, Toubiana compared Luddy to Langlois (who often visited PFA in the 1970s): “If anyone understood Langlois’s experience, it’s Luddy. The principle is simple: show everything, censor nothing, be in search of what is rare, what is forgotten, and what is at risk of disappearing…” For Luddy, this approach to programming was an extension of the political values of his youth. “Hollywood has been very successful at convincing young people that the new films from Hollywood are the only ones they need to see, even if they’re bad,” he lamented to Toubiana. “This is why I prefer that the Cinémathèque is here. In Los Angeles, it would be too close to the commercial industry.”

At a moment when a small number of corporations exercise greater and greater control over what audiences get to see, Luddy’s legacy offers us an alternate vision of how film culture could be. In Berkeley, where he lived until his death, the number of movie theaters within walking distance of the UC campus fell from six to two in the last few years. On the other side of the Bay, the legendary Castro Theatre in San Francisco is sentenced to be gutted by its new owners, who seek to transform it into a venue for live music. SFMoMA ceased its film program in 2020, and no plans exist to revive it. Each of these developments is a blow to what was once a major center for film culture in the United States, thanks in no small part to Luddy’s influential efforts. His achievements may appear impossible to replicate today, yet in reading interviews with him from the ’70s, it’s clear that it was no easier then than it is now. Rather than lamenting the state of things, we would do the greatest justice to Luddy’s memory by following in his footsteps: being curious, seeking what is unknown, and refusing to allow commerce to have the final say on what deserves to be seen.

The author would like to thank Jason Sanders and the staff at BAMPFA for their help with research for this article.

Jonathan Mackris is a writer and film programmer based in California.