In Memoriam: Charles Silver

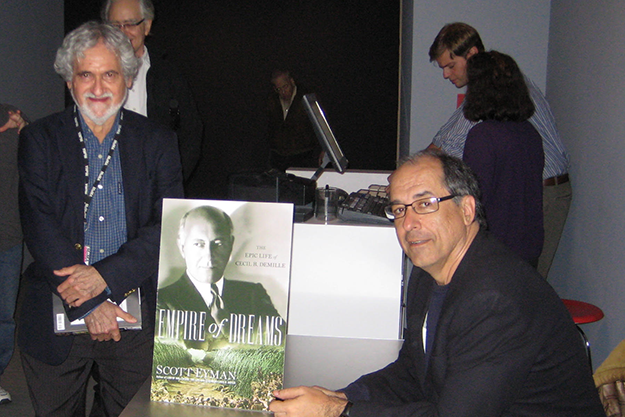

Left to right: Charles Silver and Scott Eyman

Begin at the beginning.

In 1987 I came to the conclusion that in order to avoid alcoholism brought on by desperate boredom—the occupational hazard of journalism before it was replaced by stark fear—I needed to write a book.

Since the topic I chose was Mary Pickford, and the only extant American print of Rosita was at the Museum of Modern Art, it was time to travel. There, a little gnome named Charles Silver showed me into a room with a 16mm projector, a table piled high with film cans, and turned me loose.

A day or two later, Charles dragged out something he thought I would find of interest: the original Biograph story register that contained the documentation by which the company had bought the story for The New York Hat from one Anita Loos, address 2915 F Street in San Diego.

Rosita

From time immemorial—well, since 1970—Charles had run the Film Study Center at MoMA, and every time I showed up to do research, Charles would first show me what I needed to see, and then surprise me with some arcane piece of related history I didn’t know existed. I would learn that this was typical of Charles; he was generous by nature. More than that, he was innately helpful, and eager to make your project as expansive as possible.

When we met, I knew Charles only through his writing, primarily an excellent book on Westerns, and very occasional pieces in FILM COMMENT. It was immediately clear that he was a dedicated Fordian, but I would have liked Charles if his favorite director had been Brian De Palma.

He was an enchanting, somewhat Dickensian character. He had a limp, he was invariably chewing on an unlit cigar, and he spoke in a low-pitched, murmuring monotone that forced you to lean forward if you were going to understand anything he said.

We had an immediate bond through our shared passion for John Ford, but it didn’t lead to conventional emotional intimacy. More specifically, it led to the kind of relationship that constitutes intimacy for Aspergerian film freaks, with movies serving as the only common ground for accessing the range of life.

Charles was painfully shy and quite private. I never asked him where the limp came from, and he never volunteered the information. He accepted compliments awkwardly, and didn’t give any indication he thought his writing had much to offer. I disagreed, and made a point to quote him in my biography of Ford.

Writers are competitive at best, viciously competitive at worst, and I don’t except myself. But Charles was, in his quiet, mumbling way, an outlier in that regard. He was an enthusiast as well as an innocent; once he made a private judgment as to your worth and level of intent, he would stick like Travis at the Alamo. Charles loved my books, so he generously offered many retrospectives at MoMA, and long dinners at Il Gattopardo during which we would catch up. Three or four years would go by, with perhaps a half-dozen emails or phone calls in the interim. And then it would be time for another book and another dinner.

I can’t claim to have known him intimately, and it wouldn’t surprise me if no one could. Certainly, Charles’s reputation as a union firebrand always seemed slightly out of character for those of us who knew him as a scholar, but part of what drew him to Ford was the communitarian ethic that fills the films.

I do know that Charles was a man of rare purity, untrammeled by careerist ambition. His passions were quietly stated but proudly displayed in his programming—a series on baseball in the movies; a retrospective for John Wayne during a time when he was completely out of style; his wildly ambitious multiyear Auteurist History of Film. He also had private sporting enthusiasms, among them baseball and an inexplicable—at least to me—interest in the New York Rangers.

What moved me then and now is that on some level each of us trusted the other on the deepest level. When Mary Lea Bandy was felled by a stroke, he sounded me out about applying for her job. Having no skills at management or taste for the infighting that bureaucracies entail, I thanked him but declined.

The last few times I saw him it was obvious that he was struggling; cancer had caused a severe weight loss. Late last year he told me that MoMA was going to publish a collection of the film notes he had written for the Auteurist series, a prospect that filled him with typical ambivalence. I told him that when he retired he needed to start writing seriously. He grunted noncommittally. Perhaps he knew there wasn’t time.

He finally left the museum—grudgingly—at the end of last year, but then MoMA was not a job to Charles; it was his identity. I wrote him to mark the occasion, but he never replied. He died less than two months later, on January 20.

Dennis Doros has suggested that MoMA christen the Film Study Center after Charles. It’s a perfect suggestion, albeit one that would undoubtedly embarrass Charles, at least publicly. Privately, it would mean everything to him. He might even light his cigar.

One last request, old friend: say hello to Pappy for me.

Scott Eyman has written 13 books about the movies, most recently John Wayne: Life and Legend. He teaches Film History at the University of Miami.