Gut Level: William Friedkin

This article appeared in the August 24, 2023 edition of The Film Comment Letter, our free weekly newsletter featuring original film criticism and writing. Sign up for the Letter here.

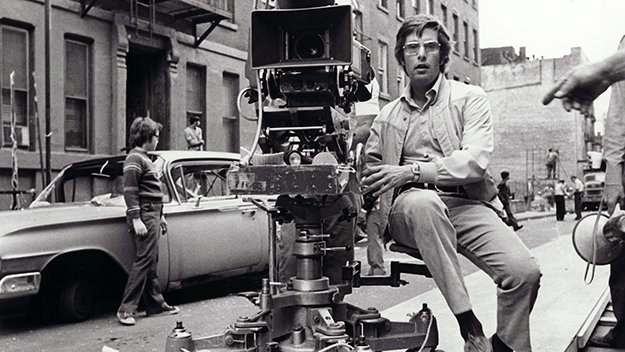

William Friedkin on the set of The Exorcist (1973)

“Most films should really be watched with your emotions, rather than with your intelligence,” William Friedkin, who died August 7 at 87, told the students of New York Film Academy in 2016. “Most of the films that interest me move me on an emotional level, or they don’t, and that’s how I watch them. I’m not looking to filmmakers or guys who work in the movie business for philosophy, or ideology, or psychology.”

If that declaration of taste also doubles as an artistic statement of purpose, it surely undervalues the intelligence (and philosophy, and psychology) of Friedkin’s meticulous films. Indeed, as always with genre auteurs, the difference between a popcorn thriller and a Friedkin thriller is that the latter can be savored both viscerally and intellectually. But the cerebrum is just the first stop en route to the pit of one’s stomach—the typical destination of a Friedkin film—and his genius for deriving spellbinding entertainment from genuine unease (and without winks or quips to offer facile reassurance) is his ultimate legacy. In Sorcerer, a truck carrying volatile dynamite attempts to cross a suspension bridge whose wood is treacherously rotten. The man guiding the driver on foot falls through a plank and pulls himself back up, but now the truck is nearly on top of him, and the driver can see nothing for the lashing rain. Also, both men are desperate criminals who have no cause to trust one another with their lives. Now consider that when the film debuted in 1977, it flopped abysmally, dismissed in many quarters as a “lesser Friedkin” for failing to equal the tension delivered by his prior two works, The French Connection (1971) and The Exorcist (1973). Here was a man who set the bar fatally high.

There were other reasons for the commercial failure of Sorcerer, a politically charged adaptation of Georges Arnaud’s novel The Wages of Fear, previously (and immortally) filmed by Henri-Georges Clouzot in 1953. It opened in the immediate wake of Star Wars (1977), the blockbuster nail in the coffin of the creative bacchanalia known as the New Hollywood—perhaps the only climate in which a maverick like Friedkin could thrive. The actioner’s title, taken from the name of one of the load-bearing lorries in the film, promised more supernatural chills in the vein of The Exorcist, but its concerns were strictly terrestrial. Above all, by the director’s own admission, his conduct throughout the shoot had “alienated the top management of two studios,” resulting in a ruinous lack of industrial support.

Mercurial behavior on set was nothing new for Friedkin. (How many movie directors have been nicknamed “Wild Bill,” anyway? One almost wonders if the name begets the temperament.) While making The Exorcist, he would fire hidden guns unexpectedly to prompt startled reactions from his cast; The French Connection’s legendary 26-block chase through Brooklyn was shot without permits or street closures, placing normal traffic and pedestrians in the path of a stunt driver running stoplights at 90 miles per hour. Sacking five of Sorcerer’s production managers in a row and going millions over budget were almost benign transgressions given his history. And to be clear, the resultant film, which has been critically rehabilitated in the decades since its release, displays none of the bloat or self-indulgence of contemporaneous auteurs-gone-wild fiascos like Michael Cimino’s maximalist western Heaven’s Gate (1980) and Francis Ford Coppola’s endearing but indefensibly profligate One from the Heart (1982).

Friedkin’s unyielding pursuit of authenticity can be traced back to a formative influence on the wunderkind filmmaker, born in 1935 to Ukrainian-Jewish emigrants in Chicago. In 1969, already with three features to his name (including the flavorful 1968 period comedy The Night They Raided Minsky’s), Friedkin saw Costa-Gavras’s political docudrama Z. It spoke profoundly to his background as a director of nonfiction TV, which he’d assumed was altogether discrete from narrative filmmaking. “It looks like [Costa-Gavras] happened upon the scene and captured what was going on as you do in a documentary,” Friedkin recalled in a 2012 interview with Fade In. “I understood what he was doing, but I never thought you could do that in a feature at that time until I saw Z.”

He may have applied documentary techniques to his next film, the 1970 adaptation of the landmark gay stage drama The Boys in the Band, in subtle ways (as in dynamic close-ups that highlight the characters’ physical, and all-too-human, imperfections—particularly standout actor Leonard Frey’s pockmarked visage). But realism suffuses every frame of The French Connection, which looks more like a gritty fly-on-the-wall doc than a polished police thriller. Friedkin’s refusal to sentimentalize extends to his protagonist, Detective Jimmy “Popeye” Doyle, played by Gene Hackman in one of the era’s defining performances. When one thinks of New Hollywood antiheroes, the Platonic ideal is not, quite frankly, the affable outlaw Clyde Barrow or the winsomely alienated Ben Braddock, but the monomaniacal, offhandedly racist, remorselessly rule-flouting Popeye—vile though he is, a figure of inexhaustible fascination. No mitigating backstory or implausible redemption arc is tacked on to make him more palatable to the audience.

The Exorcist is no less psychologically resonant, I would argue, because if you extracted the horror elements, the human interplay that remained would still arrest your attention. Embedded within Friedkin’s expert screen translation of William Peter Blatty’s paranormal page-turner are 40 minutes of Paul Schrader–worthy drama about a priest (Jason Miller) suffering a crisis of faith—mourning his mother, swilling Chivas Regal in his lonely room—and a second-wave-feminist study of an actress (Ellen Burstyn) struggling to balance single motherhood with her high-profile career. (Not for nothing were both actors nominated for Oscars.) Legions of subsequent Satanic-panic knockoffs have bypassed such detailed characterization on the road to tawdry scares, which is why Friedkin’s original remains the gold standard.

The disappointing reception to Sorcerer (which, as late as 2017, its director proudly called “the film that is closest to my vision of it before I shot it”) was followed by more critical and public drubbings—1980’s Cruising was picketed by gay activist groups, and 1995’s quintessentially of-its-time erotic thriller Jade, another of Friedkin’s personal favorites, was widely panned. His later output includes a pedigreed TV remake of 12 Angry Men (1997) that feels more like a long-overdue and exceedingly rewarding revival of a play—a good argument for taking already watertight scripts and refitting them with contemporary casts and crews. (Besides making the jury more racially diverse, it offers a chorus of brilliant performances—including what may be the best in either version, by George C. Scott.) Big-screen adaptations of two nightmare-inducing Tracy Letts plays—Bug (2006) and Killer Joe (2011)—feature direction by the septuagenarian so formally brazen and utterly cinematic, despite both pieces’ theatrical origins, as to permanently debunk the pernicious old saw that filmmaking is a young person’s game.

The publication of this article precedes the Venice premiere of Friedkin’s final film, The Caine Mutiny Court-Martial, by barely a week. In a series of memorial tweets, standby director Guillermo del Toro described the late filmmaker’s on-set demeanor as “precise, eloquent, and so full of energy that it was almost daunting to see . . . He would run long takes and produce drama beautifully.” Del Toro also shared a touching story about an actor stumbling over a difficult monologue, and Friedkin’s soft-spoken offer, despite the production’s tight schedule, to postpone shooting until the next day—a “healing [and] soothing” gesture. Whether it’s meant to be watched with one’s emotions or one’s intelligence, or both, the swan song of Wild Bill Friedkin was manifestly directed with emotional intelligence. What could be more authentic than that?

Steven Mears is the copy editor for Film Comment and Field of Vision’s online journal Field Notes, and is a contributing writer to both, as well as to Metrograph’s Journal, Bloodvine, and other publications. He wrote a thesis on depictions of old age in American cinema.