Ghost Dance: The White Crow and Nureyev

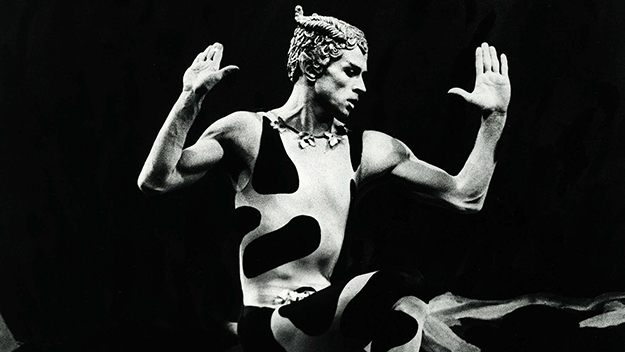

Rudolph Nureyev. Photo by Kobal/REX/Shutterstock

The life of Rudolf Nureyev might have been written for the screen. Born on a Trans-Siberian express train, raised dirt-poor in the Soviet republic of Bashkir, he overcame a late start in his ballet training to become one of the 20th century’s greatest dancers. The Soviet government was wary of his rebelliousness, but could not resist showing him off to the West as a trophy of their cultural supremacy; his dramatic defection at Paris’s Le Bourget airport in 1961 was a major blow in the Cold War. He went on to rock-star-level celebrity, an alchemical stage partnership with ballerina Margot Fonteyn, and an eclectic international career (including choreography, ventures into modern dance, and playing another Rudolf in the legendarily disastrous 1977 Ken Russell film Valentino) before becoming one of the dance world’s many losses to AIDS in 1993. But if the biopic writes itself, it does not cast itself. Nureyev possessed superhuman charisma; invariably compared to a panther or a tiger, he was worshiped for his explosive stage presence and exotic beauty—the Tatar fierceness of his cheekbones and eyebrows offset by sensuous lips and heavy-lidded eyes. As a sex symbol, he was on a par with the H-bomb.

People will persist in making biographical films about movie stars and other performing artists, despite the inherent challenge of convincing audiences to accept a stand-in for someone whose looks, voice, and physical presence they know by heart. The White Crow, Ralph Fiennes’s film about Nureyev, does not solve this problem: Oleg Ivenko, of the Tatar State Ballet Company, is a dancer who can act, but he does not remotely resemble Nureyev. However, the film mercifully sidesteps some of the other pitfalls that make artist biopics so predictably dispiriting. Faced with the task of giving shape to the disarray of a life, and accounting for the mystery of genius, they often settle for a hackneyed formula: Famous Artist, a struggling failure, has a tragically thwarted romance, which miraculously sets him or her on the path to greatness. So common is this cliché that The White Crow seems applause-worthy just for its attention to the actual work of being an artist, and its almost total lack of interest in its subject’s love life. (Of course, it is more fun to watch a dancer studying his craft than, say, a writer sitting for hours at his desk staring into space.)

The White Crow (Ralph Fiennes, 2019)

As a dance film—another genre that all too often disappoints—The White Crow gets many things right. Lovers of ballet will be relieved that it eschews the sleaze and slander that have become typical of movies about this most refined and demanding art. It does not present dancers as psychotic divas, ballet companies as snake-pits of backstabbing and bed-hopping, or ballet itself as a form of physical and psychological torture. (The film’s title—derived from Nureyev’s childhood nickname—suggests, perhaps intentionally, the inverse of Black Swan.) The classroom exercises that we see accurately depict the rigor and exhausting discipline, as well as the essential courtliness of ballet, which at heart is a physical expression of an ideal of human behavior. Fiennes also avoids the obvious but still sadly common mistake of casting a non-dancer in the lead and making do with body doubles and editorial fudging. Dance scenes are shot with refreshing simplicity, free from attempts to pump up the excitement with excessive cutting; the only real problem is that there isn’t enough dancing. The White Crow has other shortcomings. It focuses on the week Nureyev spent in Paris with the Kirov Ballet, leading up to his defection; this is intercut with flashbacks to his childhood and his training at the Leningrad ballet school. Following the current fashion in film narrative, these periods are chopped up and tossed into a chronological salad, necessitating the use of on-screen titles to orient us in time and space. It is never difficult to tell when the film returns to Rudi’s childhood, since these scenes have been digitally treated with a kind of “Soviet Gray” Instagram filter. It is always winter in Bashkiria, a land of snow and mud, almost totally drained of color, where Nureyev’s angelic mother hauls provisions on a sled in the early-morning chill, while his father is away fighting in the Great Patriotic War. No wonder that, when he arrives in a colorful, capitalist-paradise Paris, he gazes upward in awe, as the camera zooms in on the word Liberté on a monument. Sometimes, the interweaving of time periods works, as when Nureyev visits the Louvre, rising at dawn so that he can get there when it opens and have the place to himself. His rapt contemplation of Théodore Géricault’s The Raft of the Medusa is intercut with a scene of him alone at the barre during his school days, ferociously practicing, drenched in sweat, his feet thudding and brushing rhythmically against the floor. This sequence transcends its heavy-handedness to thrillingly convey the link between the corporeality of dance—flesh, muscle, bone, sweat—and its blazing, dramatic soul.

In many ways, the Leningrad scenes are the most interesting and complex. Arriving as a teenager at Russia’s most prestigious dance academy, Nureyev is at once insecure and arrogantly assertive. He insists on being taught by the celebrated instructor Alexander Pushkin, played by Fiennes (demonstrating his fluency in Russian) as a gentle, reticent, curiously passive man. Pushkin’s wife, Xenia (Chulpan Khamatova), takes a motherly interest in Rudi, bringing him soup, inviting him to move into their one-room apartment after he injures his leg, and then seducing him. Their relationship touches on the important role that older women played in Nureyev’s life—including Fonteyn and several of his other dance partners—and also evokes the stifling, oppressive intimacy of his life in Russia. A scene with a male lover indicates Nureyev’s homosexuality, but the central relationship in the film is his platonic friendship with Clara Saint (an elegantly restrained Adèle Exarchopoulos), the intelligent, well-connected Parisienne who helped to facilitate his defection.

The White Crow (Ralph Fiennes, 2019)

The climactic scene at the airport—when Nureyev is informed by a KGB minder that he is being sent back to Moscow rather than joining the rest of the company on the next tour stop in London, forcing him to choose on the spot whether to abandon his homeland forever—manages to generate considerable suspense despite our knowing how things will turn out. The ritualistic protocol of Cold War defection is absorbing, and the film is gradually anchored by Clara, who comes to understand how selfish, stubborn, and at times horrifyingly rude Nureyev can be, yet accepts him as he is. It is a fascinating paradox that this willful, freedom-loving egotist chooses an art as rule-bound as ballet, in which dancers are expected to be obedient and men’s traditional role is to chivalrously support ballerinas. Nureyev broke the rules, launching a golden age for male dancers and giving ballet a modern edge, but he also honored tradition, mounting new versions of the classics of Russian ballet during his last act, as the artistic director of the Paris Opera Ballet.

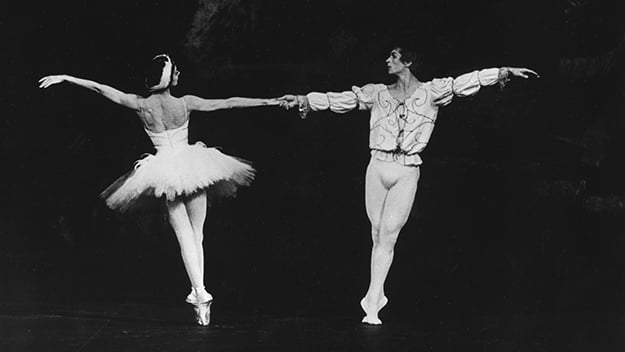

(Dame) Margot Fonteyn, Rudolph Nureyev in Swan Lake, 1967.

Photo by Neue Thalia/Upa/Wdr/Orf/Kobal/REX/Shutterstock

Ending with Nureyev’s move to the West, The White Crow focuses only on his development; the documentary Nureyev (2018), by David and Jacqui Morris, covers his entire life, with an emphasis on placing him in the context of his times. The filmmakers have assembled a wealth of archival performances and interviews, including some previously unseen footage of Nureyev dancing works by modern choreographers Martha Graham, Paul Taylor, and Murray Lewis. This is combined with newsreel footage, photographs, artworks, and original, semi-narrative dance sequences by Russell Maliphant. These elements are not just intercut, but superimposed and blended onscreen, creating palimpsest-like collages of imagery. The film’s visual effects morph to evoke the different eras it covers: from Soviet-style montage to 1960s-Hollywood split-screens to TV static and the soft, blurry color of 1980s videotapes. Some of these flourishes are merely distracting, but none of it upstages Nureyev himself. It is impossible to upstage a man who can pull off a snakeskin-patterned tunic and matching, knee-high, high-heeled snakeskin boots—the outfit Nureyev wore on “The Dick Cavett Show,” to a sustained ovation that (a bemused Cavett noted) was longer than the one Mick Jagger got.

The documentary provides insight into how the government of the Soviet Union used ballet—in moments of political crisis, Swan Lake would always appear on television—and reveals the extent to which Nureyev’s family and friends suffered as a result of his defection. (He was not allowed back into the country to visit his mother until 1989, when she was on her deathbed.) Generally admiring, and filled with the voices of his friends, the film touches on his notoriously violent temper and legendary self-regard (Richard Avedon described him, in a photo session, wallowing in a “narcissistic orgy of one”). His love affair with Erik Bruhn, a blond, coolly classical danseur noble—Apollo to his Dionysus—whom he displaced as the West’s most famous male ballet dancer, begs for its own movie. Here, a film clip of them rehearsing together in a studio is by itself worth the price of admission. But nothing is more mysterious and moving than Nureyev’s on- and off-stage relationship with English ballerina Margot Fontyen. Much is said about their magic, their chemistry, their glamour, and the depth of their affection (at the end of her life, he paid her hospital bills); but none of it is necessary once you see them dance together.

Finally, near the end of the documentary, there is an extended excerpt from a film of their signature performance in choreographer Kenneth MacMillan’s Romeo and Juliet. What Nureyev is doing in this scene—the one where Romeo finds his beloved apparently dead—is more acting than dancing, and even clipped out of the larger narrative it is devastating. (The relationship between acting and dancing deserves more attention; Louise Brooks wrote that she “learned to act by watching Martha Graham dance, and learned to dance by watching Charlie Chaplin act.”) In The White Crow, Pushkin instructs his star pupil that in dance, story is more important than technique; that steps are interconnected and have a logic, just as parts of the body are harmoniously coordinated to create “line.” But none of that film’s dance sequences are long enough to demonstrate this; they focus on pyrotechnics (jumps, leaps, turns) rather than dramatic arc or expressiveness. Much of the footage in Nureyev is likewise too brief, or too poor quality, to do more than hint at what knocked people out when he appeared on stage.

Jacqui Morris has said that one motivation for the project was the ephemerality of dance, and the desire to preserve the traces of it. Even film cannot fully capture the experience of a live performance, hence the agglomeration of different techniques people use to make up for what is absent. The best dance films of all—from Powell and Pressburger’s The Red Shoes (1948) to Wim Wenders’s Pina (2011), from Astaire and Rogers to West Side Story (1961)—are those designed for the screen, which choreograph with the camera and use cinematic space rather than a flat view of stage space. Nonetheless, we should be grateful for every record of someone like Nureyev, however blurred, choppy, or ghost-like. They offer some consolation, however inadequate, for not having been there to feel the temperature rise in the room when he came on—attacking his steps, Fonteyn wrote, “as though pouncing on a prey three times his size.”

Imogen Sara Smith is the author of In Lonely Places: Film Noir Beyond the City and Buster Keaton: The Persistence of Comedy, and has written for The Criterion Collection and elsewhere. Phantom Light is her regular column for Film Comment.