Film of the Week: The Wandering Soap Opera

The late Raúl Ruiz, who spent the larger part of his career away from his native Chile, regarded himself not as an exile, but as an “exote.” He said, “You’re an ‘exote’ when you go everywhere and each country looks like a different place, impossible to deeply understand. After that experience, you return to your own country, and your country is more enigmatic than the rest of the world.”

Ruiz’s posthumously completed The Wandering Soap Opera—to all intents and purposes his final film, although it was shot in 1990—can be seen as a returning “exote”’s attempt to make sense of a homeland that had changed in his absence. It’s hard to be sure, however, whether that primarily makes the Chile of this film “exotic,” or whether every country where Ruiz worked (among them, the U.S., the Netherlands, Britain, above all France) was made strange by the distinctive vision of a quintessentially “exotic” director.

The Wandering Soap Opera, which has its U.S. premiere at the Film Society of Lincoln Center’s current Ruiz retrospective, Life Is a Dream—is the result of six days’ 16mm shooting during Ruiz’s return to Chile for the first time since his departure in 1973, just before the Pinochet regime took power. The film is based on the idea—as Ruiz put in an interview included in Pablo Martínez’s making-of film, Exote (2017)—that “there’s no such thing as Chilean reality,” that reality in his country is a series of soap operas. Ruiz specialized in making wry comments about his homeland: one episode in his film bears the heading, “If you behave badly in this life, you become Chilean in the next one. R.R.”

His views on the fundamental weirdness of his national culture are to be taken with a pinch of salt: they’re in a spirit not that different from the way that the Portuguese, the Welsh, the Swiss talk about themselves (insert your own example). But the peculiar extremity of Chile’s destiny in the 20th century—a brutal period from which, in 1990, the nation was just beginning to emerge—explains something of the strange dreamlike tone of The Wandering Soap Opera, in which every character seems to be sleepwalking, and in which we can imagine the director too being in a state of head-spinning bedazzlement, coping with the strangeness of his return.

It’s worth noting that The Wandering Soap Opera is no more or less bizarre than any other representative Ruiz film. The delirious flavor of his work in France in the 1970s and 1980s can’t be attributed only to his experience as an exile, but stems deeply from his rich literary culture and fascination with the ontological and existential riddles of Borges, Chesterton, Stevenson, the Spanish Golden Age, the French Absurdists, various Islamic and Western philosophical texts… The Wandering Soap Opera is very much of a piece with the director’s sprawling output: its vertiginous use of mise en abyme and fragmented drift from narrative to narrative echoes both Life Is a Dream (1987), a science-fictionalization of the classic Calderón play, and his later Love Torn in a Dream (2000). The latter is arguably the nearest Ruiz came in structure to a book I once saw him carrying a copy of, Jan Potocki’s 19th-century novel-as-narrative-chain The Saragossa Manuscript (memorably filmed in 1965 by Wojciech Has).

Recently assembled for the first time by Ruiz’s widow and frequent collaborator Valeria Sarmiento (a considerable director in her own right), and premiered in Locarno last year, The Wandering Soap Opera is a gift for Ruiz fans. In a somewhat Borgesian paradox, which seems entirely characteristic, the film can be seen as a sort of sequel to the director’s actual final film, Night Across the Street (2012), a quasi-autobiographical last return to his Chilean roots and memories, also premiered after his death in 2011.

The Wandering Soap Opera is a kind of jeu d’esprit, a series of self-contained but implicitly linked episodes that seem, for much of the time, to be generated entirely by two elements: gratuitous wordplay, and parodic riffing on the conventions of the TV soap. In the first episode, entitled “People Are Watching Us,” a man and a woman—she’s elegant and mature, he’s a long-faded matinee idol turned patriarch—sit in a drawing room filled with pot plants that slowly grow from shot to shot, until the pair appear to be seated in deep jungle. He tells her how much he likes her legs, especially the left one; he says, “When I touch you, I feel like I’m traveling through Chile,” and recites a long litany of place names. They discuss Chilean divorce laws and it turns out, in typical telenovela fashion, that he’s romancing the wife of his brother (who, to make their situation more complicated, is a Catholic socialist). At one point, he offers her his muscles to eat, and whips them out of his jacket—two large chunks of raw meat. Throughout the episode, she keeps saying, “People are watching us,” although—until her husband turns up out of nowhere—there’s no one in the room. But of course, they are being watched: by us, Ruiz’s audience; by the viewers of the telenovela in which they’re characters; and, it’s implied, by the Chilean state. Plenty of seemingly casual or absurd comments throughout the film take on a chilling resonance when you remember that that it was shot immediately following the end of the 17-year Pinochet dictatorship. When, in one episode, someone talks about torture, we can assume he’s only ostensibly referring to the practices of the Spanish Inquisition.

As in all Ruiz films, there’s a thin line between the realms of life and death, and some characters here are actually dead or dying, or hovering zombie-like on the threshold—like two young men mysteriously glimpsed lying head to head in a gravel pit. A woman is visited by her late husband, who hovers in rough-and-ready cheap-TV superimposition: “I refuse to argue with the dead,” she says, defiantly. In another episode—which plays on Latin American political militancy as a maze of confused motives and rhetorics—two characters sitting in a car are suddenly shot, only for their killers to die in turn. The sequence could theoretically continue until Ruiz has run out of available cast members (there are actually 19 actors in the film, nearly all of them playing two or three roles).

In one episode, a man asks a woman whether she’s read that day’s newspaper. She replies, “No, I don’t have the time. Soap operas are a lot of work.” It’s a chilling comment about the way that, in critical periods, individuals may obsessively retreat into fiction over reality in their lives (something terrifyingly demonstrated as a malaise of the Pinochet era by Pablo Larraín’s Tony Manero). Conversely, you can see how addictive fiction, as represented by the Latin American telenovela, might provide some sort of lifeline to sanity in troubled times. But the characters in Ruiz’s film seem to be drowning in soap, as if uncertain whether there’s anything more to the world than the endless production of open-ended fictions. As the woman in that same episode complains, supposedly herself a character in a soap, “All we do is watch other soap operas and comment on them.”

One stretch of the film, overlapping chapters, could be seen as Four Characters in Search of a Telenovela: these people, ostensibly inhabiting the real world that Ruiz’s film was shot in (they’re even seen on a real street), know that they’re soap characters, but aren’t sure which soap they belong in. That the same actors turn up from episode to episode in diverse roles—making barely any effort to suggest differences in characterization—seems par for the course. I once, in the early 1980s, spent an evening in a restaurant in Portugal watching, fascinated but uncomprehending, a succession of Brazilian soaps, all with dazzling title sequences and equally tacky, rickety studio sets; several actors turned up from show to show, in different clothes and sometimes different hairstyles, but always recognizably themselves. The same applies here, where characters seem permanently lost in Soapworld, which is only one vast but specialized province of the wider Teleworld; in a bar scene, we glimpse an (apparently real) poster for a drink advertising itself as the “Telethon beer.” In an episode set in a strip club, no one’s looking at the dancers, but the TV is on and showing three women, apparently in a soap, talking about another show, Victims of Love. In the club, a woman gazes up at the screen: “How much do they earn per episode?” she asks hopefully.

The Wandering Soap Opera isn’t just an absurdist comedy about the unreality of the world. Nor is it just a dizzying infinite regress in which reality, such as it is, is mined by a series of fictions within fictions—although there comes a point at which the characters, like us, find themselves watching TV screens within screens. It’s also, if you want to put a realist slant on it, a fiction about the way that working actors and filmmakers survive in hard times. When the economic going gets tough—and presumably too, when draconian forces rule a nation—then artists are likely to find little work to do that’s at once honorable, exalted, and profitable. At such times, fulfilling roles in art movies may be thin on the ground.

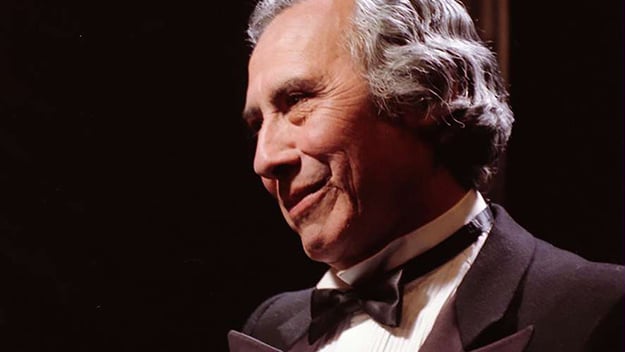

Soaps and other cheap-and-cheerful TV fodder, however, are likely to be plentiful, as long as you don’t mind being typecast, or directing stuff that sticks in your craw. The Wandering Soap Opera presents a succession of archetypes, of actors playing characters who essentially look exactly as you’d expect them to: the flighty ingénue, the nobly vampish middle-aged romantic heroine, the grey-templed older roué, assorted raffish bohemians, harassed civil servant types… I didn’t recognize anyone in the cast, although somewhere in there is Francisco Reyes, who can currently be seen as the ill-fated older lover in Sebastián Lelio’s Oscar-nominated A Fantastic Woman. One of the cast, Luis Alarcón, had worked with Ruiz on his early Chilean films, including Three Sad Tigers (1968) and The Penal Colony (1970); others had also worked with him in the past. According to Exote, the cast contains actors from stage and soap. You wonder whether, in fact, they’d all done soap service in their time; whether any of them were known primarily as TV faces; and whether Chilean viewers would have immediately identified such and such an actor as the jealous spouse or the scheming in-law on some show or other.

Ruiz wonderfully pastiches the stiffness, the talky longueurs, the abrupt discontinuity of the telenovela style— although the visual language occasionally becomes distinctly Ruizian, with bizarre camera angles, or beer glasses looming massively in the foreground. The new score, by his regular composer Jorge Arriagada, coats everything in just the perfect parodic thickness of slush. Sarmiento’s completed version bookends the film, shot in color, with two black and white sequences showing Ruiz on set: at the start, he calls “Action,” at the end, quietly announces, “OK, the film’s finished.” It’s a fond farewell touch, and a sweetly ironic one, because we know that in the Ruiz universe, no film, no story is ever finished. Dictatorships fall but art, and the desire to make it, go on. By its nature, the soap opera—however lowly it’s regarded—has a tenacious nobility of its own. Its ultimate meaning is always, “To be continued…”

Jonathan Romney is a contributing editor to Film Comment and writes its Film of the Week column. He is a member of the London Film Critics Circle.