Film of the Week: Staying Vertical

It isn’t till the very final moments that we discover the literal meaning of the title Stay Vertical, the new film by French director Alain Guiraudie. But other meanings are apparent before then. It’s partly a question of simply staying alive, and as usual in Guiraudie’s films, men’s ability to keep erect is also a key question, although it never appears to be a problem: there’s one hard-on glimpsed through a character’s pants in close-up, while lead actor Damien Bonnard appears visibly erect in the film’s most startling shot.

Note that this shot is startling not because of his erection itself—in Guiraudie’s films, that’s never a big deal—but because of the way his character, a directionless screenwriter named Léo, intends to use it. This is altogether a very perplexing film, but when you get to the ending and that other specific meaning of staying vertical, you’ll either gasp at Guiraudie’s unabashed idiosyncrasy or you’ll do that French thing of shrugging dismissively and muttering “Bof…”* as many critics seemed to when the film screened in Cannes last year.

If you only know Guiraudie from his taut, highly structured gay thriller Stranger on the Lake, then you won’t have the measure of the oddity of this director from the Aveyron region of southern France. Guiraudie’s particular genius as a low-budget filmmaker is to take ordinary, sometimes prosaic places and spin elaborate, often apparently free-form fictions around them that utterly transform the status of their reality—as in Time Has Come (2005), which converts his home territory into a landscape that belongs equally to the Middle Ages and to the Western, or his most dreamlike film No Rest for the Brave (2003), in which the reality of the world is radically undermined by bizarrely spelled road signs pointing the way to international locations (Oncongue, Riaux de Jannerot, Glasgaud).

In its seemingly improvisatory drift, Staying Vertical is much closer to Guiraudie’s other films than to the claustrophobic, Hitchcockian Stranger on the Lake. It begins with a long through-windshield shot of a drive on a country road, before the driver of the car—Léo, played by Damien Bonnard—decides to ignore an old man sitting by the roadside, ’70s heavy rock mysteriously booming out all around him, and turns back to address a young man he’s passed a moment before. There’s something rather Buñuelian here about the way that the film suddenly wrong-foots us, seeming to change its own mind about where it’s heading. Stopping to address the youth, a sulky kid named Yoan (Basile Meilleurat), Léo has the gall to use that hackneyed line, “Ever thought of a career in the movies?” Yoan decidedly isn’t interested; Léo moves on.

The next we see of Léo, he’s trudging across a windblown terrain: one of the causses (causse is translated here as “prairie”), or limestone plateau, of the Massif Central region, a frequent Guiraudie location. Here Léo meets an unsmiling young woman called Marie (the wonderfully named India Hair), who’s guarding a flock of sheep; they have a terse discussion about the wolves that are menacing the area, before Guiraudie cuts disconcertingly from a close-up of Marie to another of her hand in Léo’s crotch. Before long, the pair are an item—signaled by another close-up, this time of Marie’s naked crotch—and he has moved in with her, her two sons and her sullen farmer dad Jean-Louis. The latter is played by the scowling Raphaël Thiéry, whose face looks as if it has been roughly sculpted out of a great wodge of clay.

But Léo—essentially a drifter, having mysteriously abandoned his former life, friends, home and all—still has another life that he keeps flitting back to. Before long, he drives back to a coastal city in another part of France—it’s never named, but the end credits reveal it to be Brest, in Brittany—where he checks into a hotel room to work on a script that’s apparently long overdue. He manages to obtain an advance from his producer, but that doesn’t seem to get the script written, and eventually the producer tracks him down, locks him in a room, and makes him write the damn thing there and then. This seems a nicely self-referential comment on the way that the film refuses to cohere until it absolutely has to, although one colleague of mine is convinced that it’s just Guiraudie’s way of admitting that he didn’t know what the hell he was doing in the first place. (I don’t agree, but even if it were so, that’s not such a problem; great films have emerged from directors admitting they don’t quite know what they’re doing, 8½ being a case in point.)

Throughout, Guiraudie skips between three main locations and apparently unrelated situations. There’s the farm, where Marie soon gives birth to a third child—cue another crotch shot, this time showing the birth in all its stickiness, such an image arguably being cinema’s ultimate signifier of the real in its irreducible concreteness. Léo turns out a devoted, gentle father, but one day, the increasingly sulky Marie decides to take off with her sons and start a new life, leaving the baby behind; the film doesn’t make this decision shocking, as many would, simply treats it in a matter-of-fact way and deals with Léo’s problems in getting the baby looked after while he heads off to the film’s other destinations. The second of these is Brest, where he later winds up, baby in arms, trying to get a handout from passersby. It’s also where he has a truly nightmarish, yet oddly farcical, brush with a bunch of homeless men—all the more shocking because he’s holding his baby throughout (the film, by the way, will absolutely freak out anyone who has firm notions about appropriate methods of childcare, especially when wolves are in the vicinity).

The third location is the house of the old man seen at the start, where Léo returns in search of Yoan, whom he hopes to lure away. Yoan’s not interested, and gives Léo the slip, apparently heading off to Australia to seek adventure. Léo meanwhile bonds with Marcel (Christian Bouillette), the cantankerous codger whose house Yoan has been living in, on what basis we can probably guess. Marcel, apparently at death’s door, is forever unleashing streams of racist and homophobic invective—some of it quite outrageously imaginative—at Yoan’s expense, but like just about everyone in Guiraudie’s universe, he’s up for sex in the unlikeliest of circumstances. It should be said that Guiraudie’s view of eroticism is very much an equal-opportunity affair, and—unlike most filmmakers, especially in France—he cheerfully disregards the notion that you have to look good, or be young, to get it on in front of a camera. The King of Escape depicted a world in which the stoutest, straightest-acting middle-aged burghers of southern rural France were getting permanently priapic together. Here too, sex is always possible, in any permutations, including between the ugly and the more-or-less OK-looking, although even Léo seems rattled when Jean-Louis comes on to him—but that might just be because, even in Guiraudie’s world, sleeping with your baby’s grandfather is one transgression too outré to consider.

Nevertheless, Staying Vertical contains a scene in which an old man and a young man lie naked together and fuck; it’s the age differential that makes this quite such a confrontational flouting of taboo, of a kind that makes Gaspar Noé look like a rank amateur. It’s all the more true because the scene manages at once to be comic, touching, and entirely unexpected. It later has its payoff in Léo’s becoming a social pariah, cueing one of the most outrageous tabloid headlines ever used as a sight gag.

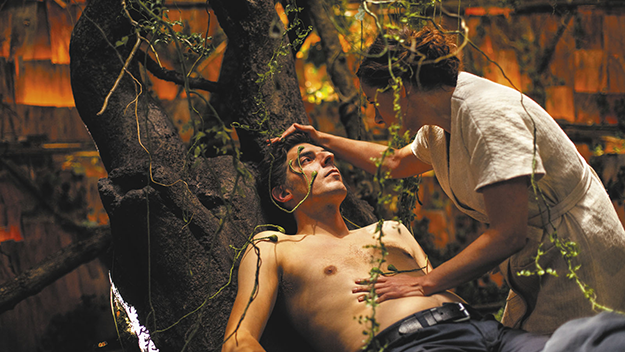

There’s a fourth location, too, seen in interludes, where the film slips into another register entirely. It’s a strangely constructed cabin in the woods, reachable only by river, where a white-coated female therapist (played by Laure Calamy, and identified in the credits as “Dr. Miracle”) tends to Léo’s sufferings, jacking him up to what would normally be electrodes, but which here are some kind of tendrils hanging off her cabin roof.

I have no idea what Staying Vertical is “about,” if it’s really about anything other than the difficulty of staying vertical. But then, with the possible exception of Stranger by the Lake, where Guiraudie concentrates fairly single-mindedly on the dual attractions of Eros and Thanatos, it’s never quite clear what his films are about—except perhaps, the joys of fiction, reverie, and unshackled libido. That, of course, is the whole appeal—and what’s mesmerizing about his latest film is the way that its narrative drifts with a logic that’s entirely unpredictable and yet, in its own way, seems absolutely coherent, even somehow inevitable. That’s why the casting of Bonnard as Léo is so inspired—he’s such an ordinary-looking guy, slightly disheveled, permanently bemused-looking, as if he’s always a couple of pages behind in the script, yet undeniably compelling in his glum but tenacious vulnerability.

Who knows how he does it, but Guiraudie has a genius for casting actors who are appealing but defiantly against the grain of conventional charisma—professionals, like Bonnard and Hair, as well as newcomers like sometime musician Thiéry—and getting them to do things that wouldn’t normally be in any player’s safety zone. As Marcel, the veteran Bouillette—whose career goes back to the early ’70s—is outstanding here, ranting and spitting venomous malapropisms, all to a permanent background of deafening progressive rock that he claims is Pink Floyd (it’s actually a mix of Wooden Shjips, Wishbone Ash, Joe Walsh, et al—the joke presumably being that, yeah right, Alain Guiraudie could afford the rights to Pink Floyd). Add a consistent tone of absolute, poker-faced normality—those tendrils notwithstanding—and somehow Staying Vertical seems like Guiraudie’s most dreamlike film of all.

* Something between “Go figure,” “Give me a break,” and “Let me come back to you on this one”—but so much more succinct.

Jonathan Romney is a contributing editor to Film Comment and writes its Film of the Week column. He is a member of the London Film Critics Circle.