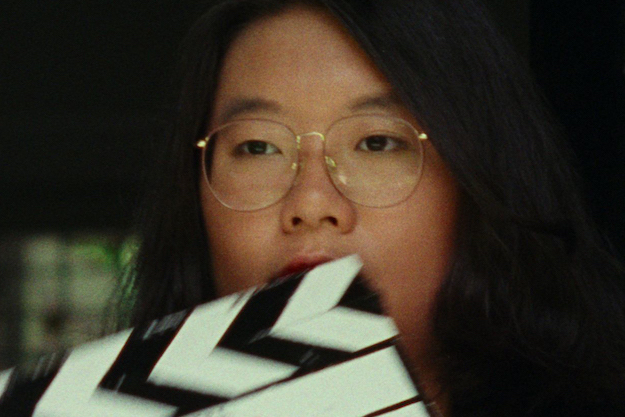

Film of the Week: Shirkers

The key point about Shirkers is that it is definitively “a film by Sandi Tan.” This documentary is the only film in existence called Shirkers, but there very nearly was another one—a Singaporean road movie made in 1992, and that one could properly have been labeled “a film by Sandi Tan and friends”—except that it would have carried the name of a different director entirely. As it turns out, there never was a 1992 Shirkers, and whether that non-existent film was in any normal sense directed by that other person, one Georges Cardona, is one of the mysteries that emerge from the actual Shirkers, the very entertaining documentary that Tan has now made about the nightmarish abortive start to her moviemaking career.

On one level, Shirkers is a memoir—a fond, self-deprecating mulling-over of Tan’s crazy, inspired, partly embarrassing but furiously creative youth. “When I was 18, I had so many ideas that I hardly slept at all,” she remembers, and what’s great about Shirkers is the way that it summons up a torrent of thoughts, images and sounds from a multitude of sleepless nights. Over a scrapbook-style assembly of film and video clips, photos, animations, what have you—the result coming across rather like a more cheerful Riot Grrl answer to Jonathan Caouette’s Tarnation—Tan remembers her teenage years in the Singapore of the ’80s, a time when “the state and the family were constantly in your face,” and when “the government was so uptight they even banned chewing gum.”

It wasn’t a great time to be a creatively minded young woman. In other words, it was a great time to be a creatively minded young woman, as the rebellious teenage Tan found out together with her school nemesis turned best friend Jasmine Ng—14-year-old outsiders who were into the Coens, Jim Jarmusch, and obscure blues. They went their own way, falling out with a prominent but very boys’-club Singaporean rock mag (“We were way too punk for them”) and living by the principle that “hysterical was superior to ordinary.”

In a burst of imaginative energy, Tan wrote the script for a film to be called Shirkers, a low-budget pop culture odyssey that would be a time capsule of the Singapore she knew, framed as “a road movie in a country you could drive across in 40 minutes.” Tan would play the lead, a 16-year-old killer named S., and the film—a collaboration between her, Ng, and their friend Sophie Siddique Harvey—carried traces of their U.S. indie passions, including Heathers, as well as Singaporean genre movies that preceded them, notably 1978 actioner They Call Her Cleopatra Wong.

To a dizzying montage of clips and fragments, Tan gives us a voiceover résumé of the film that Shirkers would have been: the delirious coming-of-age journey of a heroine who’s a sort of Singaporean female Holden Caulfield, who meets a “visibility inspector,” whatever that is, and abducts his son; meets a “funny guy” called Montana Bob; falls for a mystery man whom she then has to kill; encounters a self-made man who’s made a fortune in sticky tape; and is destined to lead people to another world, although “it’s not clear if it’s heaven, hell, or a supermarket.” Judging by what we see, the journey also involves little girls in pink ballerina costumes, kids in masks, a man selling multicolored toothbrushes, and lots of goofy early ’90s novelty sunglasses. In the movie, Tan concludes, “things happen, or maybe they don’t. Because maybe the whole thing was a dream after all.” In fact the plot, remembers Harvey, interviewed today, was immaterial: “It was a mood piece.” Tan asks another friend from that time, whether he thought the script was childish. “Yes,” he replies, “but that was the beauty of it.”

Shirkers ’92 looks as close as a movie can get to being a free-associative, glue-it-all-down fanzine in celluloid; as Tan’s rock critic friend Philip Cheah says, “This film could have been a rallying call, that it’s OK to try anything.” Instead of which, it remains—as Harvey puts it—“the ghost in Singaporean history.” Shirkers never emerged, to young Tan’s bitter chagrin, but partly (you suspect) to the relief of Tan today. What happened?

What happened was a man called Georges Cardona, who emerges from the film as what you might call a “toxic Svengali.” He was an American who ran a filmmaking class than Tan attended, and was a charismatic figure of the sort that can make people believe, as another once-dazzled former acolyte puts it, that an adventure was about to happen. Tan fell under his spell, somewhat to her mystification today: somehow she ended up driving across the U.S. with a much older married man, believing he was her best friend (the relationship was platonic, but she started getting “weird signals” en route, before he made advances).

Cardona, who seemed to know the filmmaking ropes, became the designated director of Shirkers, although what he really did on the film remains nebulous—until his actual role in it becomes clear. Meanwhile, it was Tan, Ng, and Siddique Harvey who put their hearts and souls—and eventually their savings—into the project. There are aspects of the making of Shirkers which are endearingly amateur in the classic guerrilla indie style, like the way the team enlisted a group of senior citizens who may not have known what they were getting into, or Siddique Harvey’s faking of a seizure in order to draw a crowd for one scene. But otherwise, the team did anything but shirk when it came to putting things together: assiduous location scouting, elaborate and highly professional storyboards, even the hiring of the biggest dog in Singapore.

And then Shirkers disappeared, and with it Cardona—who vanished from Tan’s life, taking all the footage with him, and leaving behind only a series of voice messages on cassette, in a creepily affectless voice. It would be a spoiler to reveal too much about what happened later, and how Tan—having become a film critic, then a Columbia film student, then a novelist—was miraculously contacted, across the years, by this ghost film that she’s all but forgotten. Suffice to say that the second half of the documentary becomes a detective story in which she—together with other victims of Cardona’s dubious, damaging charm—goes in search of the truth about an exploitive dilettante and mythomaniac.

The happy ending of Tan’s film is that it brings together people who once figured hugely in her life—together with others she never previously knew, including the late Cardona’s widow, who prefers to appear nameless and face blanked out (she’s credited as “The Widow”). Sophia Siddique Harvey is now chair of film at Vassar, while Jasmine Ng is an activist and filmmaker, who made the 1999 “motorcycle kung fu love story” Eating Air (which, from the clips shown here, looks a blast). Ng, who showed her defiance for authority by always brazenly chewing the proscribed gum on set, still shows traces of the schoolyard enemy of Tan’s that she once was. “You’ve always been an asshole,” she tells her—and her saying it as much a sign of undying friendship as is the fact that Tan includes it.

It’s clear that the disappearance of the apocryphal Shirkers (Georges Cardona, 1999) was a life-scarring calamity for Tan, and perhaps a major loss to Singaporean film history and film history in general, who knows—although, between the lines, Tan seems to be telling us that we haven’t really missed much. But that its vanishing should have resulted in the very enjoyable—and, in its flip way, oddly profound—Shirkers (Sandi Tan, 2018), well, that’s simply a miracle, and a delight.

Shirkers opens October 26, and on October 30 at 7:00 p.m., The Film Comment Free Talk with Sandi Tan takes place at the Amphitheater at the Film Society of Lincoln Center.

Jonathan Romney is a contributing editor to Film Comment and writes its Film of the Week column. He is a member of the London Film Critics Circle.