Film of the Week: Ryuichi Sakamoto: Coda

“Coda” might be considered a tactless term to apply in a documentary about a musician who, at 66, is perhaps in the autumn rather than the winter of his career. But Stephen Nomura Schible’s portrait film Ryuichi Sakamoto: Coda is about an artist very much concerned, these days at least, with the idea of endings, and of what comes after. Japanese composer, soundtrack writer, and electronics pioneer Ryuichi Sakamoto was diagnosed in 2014 with throat cancer, and much of Schible’s intimate film shows him musing courageously and wryly on his own mortality: having currently beaten the condition, Sakamoto says he knows he might live for another 10 years, or 20, or possibly just one. Inevitably, this gives particular urgency to the work of someone who–having started his current career in his twenties–has barely stopped working since and, despite a reluctant obligatory hiatus, isn’t inclined to stop now.

But the physical devastation that Sakamoto has experienced–and on which he comments with robustly philosophical humor–is paralleled by the planetary devastation that is another theme of the film. Coda begins with a vista of a blasted landscape that could be the setting for a Tarkovsky film. It’s actually the zone around the Fukushima nuclear site, and Sakamoto is first seen, in a wonderfully resonant sequence (word play intentional), investigating a piano at a nearby agricultural school. The piano survived the tsunami which so catastrophically hit the region; it floated on the flood waters and somehow emerged with both its casing and its inner workings intact. There’s a waterline on its side and one, showing the flood level, on the curtain in the background, which now strangely looks like scarred concrete. Sakamoto picks at the piano’s innards, hits the keys. The sound seems mangled, distorted, but in a way, it’s the pure sound of survival, and Sakamoto–who will sample this piano to use in new compositions–has captured what’s most poetic about it.

Environmental catastrophe has been a key preoccupation of Sakamoto in recent years. He has lent his voice to the campaign against reopening Fukushima’s reactors, and the film also shows him on a trip to the Arctic Circle, where he records the sound of trickling water from melting ice that, he notes, existed in the pre-industrial age: it also finds its way into his work.

Described this way, Coda could come across as the portrait of a conceptual tourist, a globetrotting flâneur (he is, after all, of the generation of David Byrne and Peter Gabriel), cherry-picking global reality for vague ideas to turn into sounds and spectacle. One has, for example, to take it on trust that the anti-nuclear composition “Oppenheimer’s Aria,” briefly glimpsed here in performance–using clips from Hiroshima Mon Amour and a loop of the nuclear physicist’s famous “destroyer of worlds” line–is a substantial statement, not just an inflated, somber spectacle.

But Sakamoto does come across as an engaging, insightful ideas man. Apart from the discussion of his health–which is intimate enough as self-revelation goes–we don’t learn anything about his personal life (according to Wikipedia, he has two children with his current partner) and in his New York apartment and studio he is only seen alone. The impression created–which may be partial or misleading, but which establishes a certain persona–is of a retiring, solitary thinker, someone currently engaged in a pensive process of re-investigating the world around him. Sakamoto, though, doesn’t come across as any sort of eccentric–despite an endearing shot in which he sticks a plastic bucket on his head to contemplate the thunk of falling raindrops.

Archive material and film clips recap Sakamoto’s career, from the electronic pop guru of the 1980s, through his early soundtracks, to his current status as somewhat cerebral creator of chamber music in a more or less ambient vein. There’s live footage of the band that made him famous, Yellow Magic Orchestra, whose 1978 number “Tong Poo” now sounds disconcertingly like prog-funk, just a step away from the likes of Level 42; and a delightfully artless interview in which the young Sakamoto explains that computers are useful because they can play the fast stuff that humans can’t (although he goes on to show that his hands can pretty much match any sequencer for sheer velocity). He’s also seen in 1984 in a snazzy sport jacket and comically horrible blue and green eyebrow make-up, commenting on the economic and technological boom that transformed Japan into an international locus of fantasies about the hi-tech future.

Sakamoto also recalls, with some amusement, his soundtrack work: his own cheek in insisting that he would only act in Oshima’s Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence if he got to score it as well, and his athletic feat in writing a vast amount under intense pressure deadlines for Bertolucci’s The Last Emperor. When he told Bertolucci that a point-blank rewrite request was all but impossible, the maestro imperiously replied, “Ennio Morricone would do it”; how could Sakamoto resist a challenge like that? We also see Sakamoto at work on the score for The Revenant–and given how bombastic some of that film’s sounds are, it’s fascinating to see him approach things in a DIY way, tinkering at home with a violin bow on a gong, or running a teacup over the surface of a cymbal.

Having made his reputation as an arch-futurist, Sakamoto is now thinking a lot about the past, and about the transcendental. He has become preoccupied with the sounds and images of Tarkovsky’s films–Solaris is extracted here–and particularly with his use of Bach’s chorales. Inspired by them, he writes a chorale in his own style–you can hear the results on his recent album Async–although it’s a bit of a comedown, after his spare solo piano run-through of the piece, to hear it pumped up into a ponderous, even kitsch synthesizer extravaganza at a recent concert.

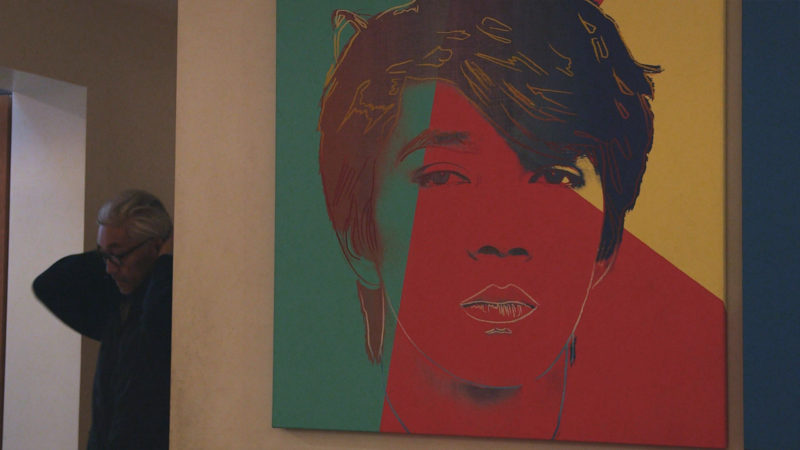

Sakamoto is fascinating to watch. He’s a charming, lively presence, and it’s always a pleasure to watch his expressions of delight and surprise at the new sounds he’s discovering, his own or nature’s. He also, despite his illness, seems to have beat the aging process in a way that many of us will feel is deeply unfair: he looked impeccably gorgeous in his youth (as witness a glimpsed Andy Warhol portrait), but his professorly autumnal image–grey bob, sober monochrome wardrobe, chic savant glasses–suits him even better.

He’s also fascinating to listen to, especially when arguing that what we think of as instruments going out of tune is really a question of materials returning to their natural state: what we consider to be natural harmony is entirely imposed and unnatural. The tsunami piano is an emblematic case of an instrument, as he puts it, “retuned by nature.”

I wish I felt, though, that Sakamoto’s music was as captivating, and as conceptually challenging, as his statements about it. As with other currently fashionable contemporary composers–Nils Frahm, Johan Johanssson, Max Richter–Sakamoto’s sounds are often reassuring rather than unsettling, and much of his work draws on a traditional repertoire (elements of Debussy, Satie et al, even echoes of Michel Legrand) that aren’t necessarily designed to rewire your listening circuitry. Schible has appealingly and elegantly given us the life; maybe it’s just this listener’s problem that the work itself comes across as more than a little bit lifestyle.

Jonathan Romney is a contributing editor to Film Comment and writes its Film of the Week column. He is a member of the London Film Critics Circle.