Film of the Week: The B-Side: Elsa Dorfman’s Portrait Photography

Errol Morris’s interview films are notorious for using his device the “Interrotron”—devised for getting subjects to talk directly to camera, and named by his wife, Morris has said, for its combination of two key concepts, “interview” and “terror.” In Morris’s new film, there’s no sign of this contraption, nor any hint of terror—it’s hard to remember any of his subjects talking about themselves with such cheerful ease as the good-humored artist portrayed in The B-Side: Elsa Dorfman’s Portrait Photography. But, more than any of Morris’s films, The B-Side is directly about the mystery of capturing a person’s identity on film, whether it’s moving or still. Elsa Dorfman, as a veteran photographer specializing in the mystery of the moment—captured specifically by large-format Polaroid cameras—knows more about this topic than most people, and demystifies it with bracing readiness. Forget any of the philosophical mysteries you may associate with discussions of the still image and the revealed self. “I’ve always been into the surfaces of people,” Dorfman confesses. “I am totally not interested in capturing their souls.”

Whether or not Dorfman does reveal her subjects’ souls—and you’d be churlish to say that she didn’t, given how vital and eloquent many of her images are—Morris certainly seems to capture some of Dorfman’s own, as she affably holds forth about her life and work. Now 80, Dorfman, based in Cambridge, Mass., came to photography late—she says she didn’t pick up a camera till she was 28—only really adopting her craft when another practitioner handed her a Hasselblad and suggested it might suit her. As a young woman, Dorfman hung out at the Grolier Poetry Book Shop in Cambridge, where she met a diverse literary crowd: her portraits from that milieu include Charles Olson, Robert Creeley, Robert Lowell, and Jorge Luis Borges. She went to New York and worked briefly at Grove Press, then at the height of its notoriety and of its primacy as a cultural salon. One day, in walked Allen Ginsberg and asked, “Where’s the can?” She had never heard the word before; they became lifelong friends. He became a regular subject; she in turn became his subject when he later picked up a camera.

Dorfman didn’t stay in New York for long; it wasn’t her kind of place, she says. “There was no woman that I met who wasn’t an alcoholic, who wasn’t promiscuous, who wasn’t a druggie, who was creative or had an interesting life.” She got a degree as an elementary school teacher and taught in Concord before that person with the Hasselblad told her she could be a photographer. “Nobody had said anything to me except, ‘You could be a jerk.’” Dorfman has a penchant for this sort of self-effacing jokiness. Asked by Morris, when shown a nude portrait of Ginsberg, whether she had suggested the nudity, Dorfman does a mock simper: “No, I was a good Jewish girl.”

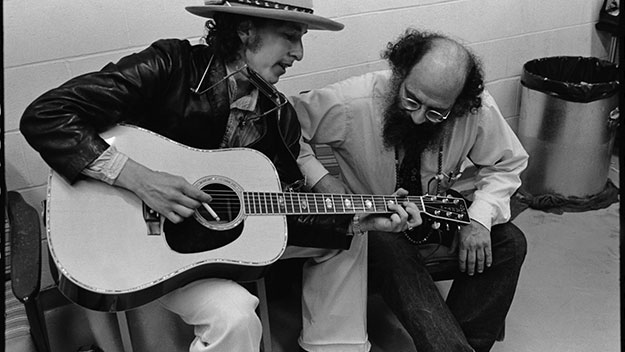

Dorfman got to photograph more famous people: from a fertile ’70s stretch, W.H. Auden is here, as are Andrea Dworkin, Anne Sexton, Joni Mitchell with beret and autoharp, and Bob Dylan backstage during the Rolling Thunder Revue tour, hunched close over a guitar with Ginsberg (a favorite of Dorfman that she has titled The Music Lesson). There are also friends and family: Dorfman’s lawyer husband Harvey, a silent presence glimpsed only intermittently, turns up in one vintage shot as a youngish man, shirtless, beaming and very hairy.

Dorfman’s breakthrough in finding her artistic identity was her adoption of the Polaroid as her chosen medium—the Polaroid Corporation was founded in Cambridge—and especially the company’s giant 20 x 24 format, for which there were only five cameras in existence. Dorfman was never a “pet” of the company she says, never even got a box of film for free; but by hanging around the business for long enough, and by “being a nag,” she says, she eventually got to install one of those five cameras in a studio space of her own, and the 20 x 24 portrait became her trademark.

The film’s title comes from the fact that Dorfman has always taken two large-scale pictures of her subjects. There’s therefore an “A” print which the subject takes away to keep, and a “B” print, which she holds onto, and which can be very different. This “B-side” to the official finished product may not necessarily be superior or more revealing, just different—in one, the subject has accidentally been decapitated by some fluke of exposure—but it’s clearly the version that Dorfman prefers, the one that catches subjects off-guard, or with their imperfections more exposed. Chatting in her studio with unfailing lucidity about her craft, but with absolutely no trace of ceremony, Dorfman talks about how “truth” in photography is an absolute myth: all you’re getting is the split second at which a shutter happens to be displaced, and the convention we attach to it is that a moment of truth is revealed. That’s what Dorfman loves about photography, she says in a revealing 1970s TV interview: “It’s not real at all.” Nor is the craft a big deal that needs to be dressed up in words: the matter-of-fact nature of her chosen art is one thing that seems to especially appeal to her. “You look for a narrative—but there probably is no narrative. You don’t go by a script, that’s what I’ve decided.”

The magic of Polaroid photography, on which the technology was so long marketed—before it was, relatively recently, laid to rest by the company’s later owners—derived from the way that its images would slowly form on paper before your very eyes. Dorfman’s own identity seems to have formed in a similar gradual way. We see self-portraits of her over the years, but in the earlier ones it’s hard to know who we’re seeing: her face is oddly blank, placid, somehow refusing to interact with her own camera, as if she would rather erase her own presence. The characterful, wisecracking, irreverent Dorfman we see at ease in her studio today seems to be someone who has come into being over the years in front of her own camera, as if only slowly becoming herself: a late developer, you might say, if you wanted to indulge in photographic wordplay.

This likeable close-up portrait may not be one of Morris’s most substantial films, but it’s his most likeable and most casual. That’s only natural, as it depicts probably his most relaxed subject, who’s visibly at ease being herself and entirely free of mystificatory notions of what she does. Surprised by her present-day visibility after years of being snubbed by the art photography establishment—“For so long I was at the bottom of the list… I just kept ploughing along”—Dorfman doesn’t make a big deal about her understanding of human nature. But just look at the thousands of people she’s photographed—adults, children, people you recognize, but mostly people who just wanted to have their picture taken by a good professional—and you can’t help thinking Dorfman knows a lot about people, and about their souls, even if she is supposedly only interested in how they look. The most heretical thing she says as an artist, if you’re attached to the idea of capturing souls—and to the notion that souls should be depicted in all their bleak, stormy depth—is that she was never one for the bad times. “When you’re down,” she says, “it’s enough, you don’t need a picture of it. I’m not good at”—she puts on a raspy the-end-is-nigh voice—“‘Oh yes, it’s really bad, your mother is a witch, your husband is awful, the food is lousy.’” Yes, photography can be a sorrowful art of mortality—especially when the traditional technology is dying, the prints are super-fragile, and mortality is written into the very fabric of the practice (“Maybe that’s when photographs have the ultimate meaning,” muses Dorfman in a rare moment of quizzical melancholy, “when the person dies”). But ultimately, she wants people to feel better, in front of the camera, and looking at themselves: “Look, it’s easy,” she says, “let’s have fun.”

Jonathan Romney is a contributing editor to Film Comment and writes its Film of the Week column. He is a member of the London Film Critics Circle.