Film of the Week: The Plagiarists

Images from The Plagiarists (Peter Parlow, 2019)

Peter Parlow’s micro-budget The Plagiarists is a concise rebuttal of the idea that all feature films need to be substantial with a capital S. It’s a curious sliver of a provocation; you may not always feel it gives you a huge deal to engage with while you’re watching it, but it certainly leaves you with plenty to chew over once its 76-minute running time is over.

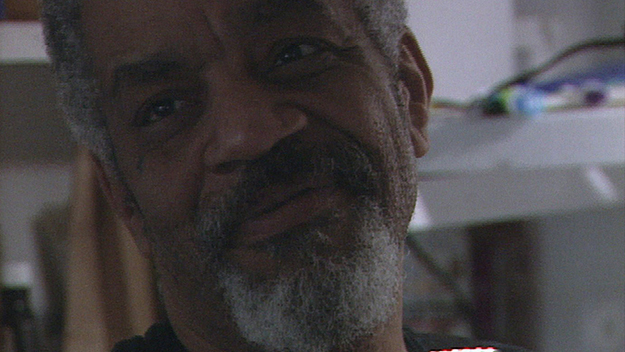

The story comes across like the stuff of mere anecdote. One winter, couple Anna and Tyler (Lucy Kaminsky and Eamon Monaghan) are heading off to the country to visit a friend, Allison. Their car breaks down, and a friendly passerby offers to help them out, eventually offering them overnight hospitality while they wait for repairs. Anna, a writer with a long piece in the works—she’s uncertain whether to call it a novel or a memoir—gets talking to their host, Clip (Michael “Clip” Payne), and listens enthralled as he spins a poetically elegant reminiscence of his childhood.

Next summer, the couple are again en route to see Allison. Anna is reading a book—I won’t spoil things by revealing which one, but it’s a currently very popular first-person work by a European writer whose name gets comically mangled in the course of this second act. Turning a page, she’s shocked to realize that Clip’s apparently autobiographical reverie was actually a verbatim rendition of a key passage in the book. Anna is baffled—why would someone do something so weird, passing someone else’s words and experiences off as their own? Then she feels humiliated, violated, thoroughly taken advantage of. She had subscribed in good faith to Clip’s lyrical candor—“I gave my complete attention to this man, innocently assuming those words were heartfelt and personal and genuine…”—believing him to be “Solomonic and deep and profound.” It turns out he was plagiarizing all along. But perhaps Clip is just a convincing, spellbinding actor—why, after all, shouldn’t he be?

As the couple argue about the meaning of Clip’s imposture, this apparently trivial episode expands way beyond its apparent significance. It takes on dimensions of both farce and outrage, and I couldn’t help thinking that the situation was very like a Seinfeld episode—possibly because Monaghan, who plays Tyler, not only looks remarkably like the young Jerry Seinfeld but also captures the toothy, agitated, self-righteous smugness of the comic’s TV persona. Was he cast for this very reason? It’s possible—after all, The Plagiarists is very preoccupied, both in style and subject, with the 1990s.

As the couple’s argument about Clip goes on, the affair throws up a whole slew of contemporary issues—the question of truth and authenticity, the ownership of original ideas as opposed to their artistic execution, the potentially racist implications of Anna’s anxiety. Does she, a white woman, feel that Clip, as an African-American, isn’t entitled to the same insights and expressions as a hallowed European author? Not unrelated to the last issue is a nexus of sexual anxieties. Tyler can’t help raising the possibility that Clip—whom he sees as having tried to seduce Anna with his speech—has in some sense raped her. Certainly, the film’s first section constantly plays on Tyler’s, and our, sexual nervousness about what is happening: teasingly, the bottle of wine that Clip reaches for is labeled “Ménage à Trois,” and when the couple hear creaking bedsprings and a mystery woman moaning in passion somewhere in the house, Tyler at first assumes it’s Anna.

The Plagiarists appears on the surface to be a drolly mocking story about white denizens of the culture world having their sense of security disrupted by assorted inexplicables—notably by a black man doing something seemingly innocuous but that seems infinitely threatening because they can’t fathom it. There are several mysteries around Clip, who appears to be an acquaintance and neighbor of Allison. For one thing, we don’t understand his connection to the pre-teen white boy who lives in, or is staying at, Clip’s house, who sleeps upstairs but doesn’t join the adults for dinner. Then there’s the question of why Clip’s backroom is a treasure cave of vintage camera equipment—including a Sony VVW200, which he offers to Tyler, a professional DP, for the Evian ad he’s been commissioned to shoot. “Evian would kill me if I shot on this thing,” Tyler comments; instead, he says, they’d insist on using an expensive state-of-the-art model, then spend $10,000 on postproduction to make it look as if it was shot on the VVW200.

The Plagiarists itself, if I understand right, is shot on that very camera—and constantly reminds us that it is. A series of harsh, fuzzy images fill the screen when Clip is telling his story—trees in the snow at night, a yellowy study of a ceiling fan—before a crash and a wobble suggests that we’ve been seeing what Tyler is shooting before he drops the camera. Overall, the look of the film, with its manifestly clunky preponderance of close-ups and medium shots, refers back to a certain style of no-budget independent cinema, American and other. Overt references are made to Dogme 95, which Tyler is vaguely aware is Norwegian or Danish (“What’s the difference?”), underlining the difficulty of telling authenticity from artifice, “natural” expression from creative game-playing.

On a simple level, there’s accessible, enjoyable, more or less unproblematic stuff to latch onto here. There’s a mystery story—what exactly is going on with Clip? There’s the story of Anna who, with Alison’s encouragement (they have a long conversation scene towards the end), overcomes her self-conscious awkwardness about writing, facing up to her very contemporary anxiety that the written word can’t compete with the more demonstrative prestige of the filmed image. And there’s a ripely comic character study, with the increasingly unlikeable know-all Tyler revealing his pomposity, prejudice, and pettiness: “What kind of request is this—‘pick up lattes’?” he whines with dyspeptic incredulity at a note from Allison. The dialogue also dips in and out of patches of pure non sequitur surrealism. After an exchange in which Tyler introduces the topic of Justin Bieber into a discussion about cameras, Clip counters, “Modern cameras have a hedonistic pout?”

Somehow, however, The Plagiarists feels like one thing in its first third (captioned “Winter”), then something entirely different in the second (“Summer”)—as the revelation about Clip sparks the debate about ideas—and then another thing again in the brief coda section (“Winter” again, but apparently a prequel to the first winter, rather than chronologically following “Summer”). The coda—a series of wintry images accompanying a voiceover letter to Anna from Allison (Emily Davis)—leaves us further perplexed about what we’ve just seen, its meaning, and what kind of film this is, especially when the end credits reveal that in many ways this has been a “sampled” film. Rather than “plagiarizing,” hiding its sources, Parlow’s movie credits passages from the celebrated European author; from a Guardian article about the relative value of books and movies; and from an episode of NPR’s Fresh Air radio show in which critic Justin Chang discusses Lynne Ramsay’s You Were Never Really Here. That film’s relevance here is unclear, although it triggers a bizarre in-car discussion about whether sex slaves really exist or are somehow an illusory side effect of 9/11, but perhaps the title is a clue. Maybe it’s there to signal to us that there’s no “here” here, no stable ground to settle on in The Plagiarists. In addition, the film’s score—including cocktail jazz, funk, and the glimmering keyboards that accompany Clip’s speech—is taken from available source music on the website Pond5.com.

Co-written by writer-director Robin Schavoir and filmmaker/artist James N. Kienitz Wilkins, The Plagiarists itself comes across as an act of imposture. It feigns to be a throwaway comedy of character and situation while really being a discursive package of philosophical and theoretical arguments, and one that manifestly, increasingly unpicks itself and displays its contradictions as we watch. Various effects are built in to notify us that we’re not quite watching the film we think we are: including the deliberately retro visual execution, rough ’90s-style video indeed, and the odd fact that Clip and the other characters never appear in the same frame. Reportedly, Payne—not usually an actor, but a musician and a long-term member of the Parliament/Funkadelic collective—never even met the other cast members.

Clip’s ripely toned, incantatory delivery of his “faked” reminiscence in his languid basso (ah, but do I mean Clip the character, or Michael “Clip” Payne the performer?) is a mesmerizing moment, a five minute passage that stands out as being foregrounded, as if separate from the rest of the film and tonally at odds with it. Which is the point. We come to realize that it has in a sense been pasted into the movie, a collaged object. The Plagiarists is an elusive, alluring, sometimes maddening thing—not so much a narrative film in conventional terms, more like an artifact, as “Mixed media: dialogue, actors, video camera, American indie movie.”

Jonathan Romney is a contributing editor to Film Comment and writes its Film of the Week column. He is a member of the London Film Critics Circle.