Film of the Week: Pasolini

Images from Pasolini (Abel Ferrera, 2014)

“To scandalize is a right.” You can imagine that motto being tattooed somewhere close to Abel Ferrara’s heart; it was a declaration of Pier Paolo Pasolini, who went on, “To be scandalized is a pleasure. And I believe those who refuse the right are moralists.” It’s unlikely, however, that many moralists today would be particularly scandalized, pleasurably or otherwise, by Pasolini, Ferrara’s tribute to the late Italian filmmaker, writer, and thinker. Made in 2014, Pasolini vividly, but perhaps a little reverently, covers the last days before its subject’s brutal and much-debated death. It also delves into his social and political thought, his imaginative universe and—to a degree—into his personality, although you emerge from the film having more of a sense of the world that Pasolini inhabited, the turbulent Italy of the 1970s, than of who he was.

Pasolini certainly doesn’t resemble any other film by Abel Ferrara, but then again, it doesn’t resemble anything that the Italian director made. Written by Mauricio Braucci and based on an idea by Ferrara and Nicola Tranquillino, it’s a sort of free-wheeling assemblage of ideas about Pasolini—a mix of biopic, discourse, dramatized fragments of his literary writing, together with Ferrara’s evocations of sections from Porno-Teo-Kolossal, the epic parable that Pasolini never got around to making.

His scoop in those sequences is to cast Ninetto Davoli, the director’s long-term muse since the early 1960s, as the apocryphal epic’s lead (he was to play the sidekick role). Davoli—in his mid-sixties when Pasolini was made—is now a stocky patriarch with a resplendent mop of snowy hair (and a bizarre, hitherto-unsuspected resemblance to latter-day Richard Gere), but still recognizably the toothy, ebullient clown of yore.

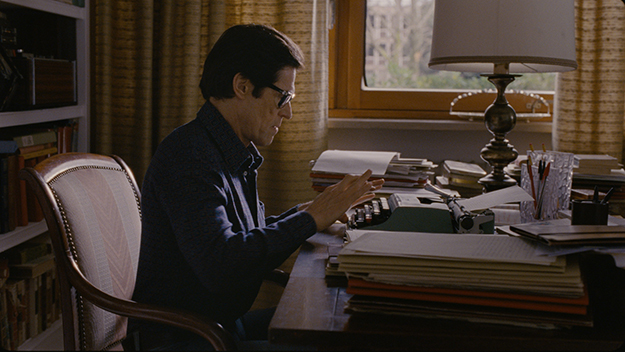

Pier Paolo Pasolini is played by Willem Dafoe, and the resemblance is so extraordinary that you’d almost be happy gazing at a still of Dafoe for 84 minutes, marveling over the tense brow, the leathery cheeks, the frown behind the heavy dark glasses—uncannily Pasolini himself, and the absolute embodiment of the auteur as saturnine penseur. Dafoe approaches the role respectfully and with a commanding sense of the absolute seriousness of the man. We also get Pasolini’s gentler, compassionate side—the austere intellectual as jovial uncle—as when he sits in a trattoria, tenderly cradling the baby of Davoli, here played as a character by Riccardo Scamarcio. The warmer Pasolini emerges too in the scenes where he meets Pino Pelosi (Damiano Tamila), the young man who would accompany him to a fatal rendezvous on the beach at Ostia on November 2, 1975. Yet despite these glimpses, the film tends to fixate on a colder, cerebral Pasolini, the abstract thinker and political polemicist, and this is rather where the film, and Dafoe’s performance, come undone.

For one thing, Ferrara has taken the odd decision to cast Italian actors and have them speak English in Italian accents, while Dafoe, with his undisguised American accent, often finds himself speaking dialogue, taken from Pasolini’s interviews, that sound awkwardly translated from the Italian. It takes an extraordinary actor not to choke on lines such as, “Refusal . . . has to be great—absolute—absurd,” or “The meaning of this parable is the relationship of the author to the form he creates.” And while Dafoe delivers them with a serious, reserved intensity, the interview sequences in which they feature feel formal, as if they belong in a staged dramatization of Pasolini’s statements; perhaps if Ferrara had made a point of accentuating their theatricality, they wouldn’t have felt so awkward.

Pasolini presents both Italy and Pasolini’s career in a state of crisis—which, in the early ’70s, they both were—with the director in the position of a public philosopher constantly sought by the media to deliver his often apocalyptic diagnoses on the state of his nation and of Western society. In fact, the film all but suggests that Pasolini’s career as a filmmaker was effectively a sideline to his presence as an intellectual guru and scourge of consumerism—but then, Pasolini himself, when asked to define himself, replies, “On my passport, I simply put ‘writer.’”

The film is set after the completion of Salò, Pasolini’s most scandalous film (which was long considered, indeed, as cinema’s most scandalous). Salò is briefly excerpted at the start (“Are those actors masochists?” a journalist asks), and we hear that it faces censorship in Italy, but it soon disappears as a topic. Italy, meanwhile, is in turmoil, in the thick of the so-called “Years of Lead,” with political violence erupting both on right and left.

One of the film’s most perceptive takes is the way that it roots Pasolini—this supposedly distant, lofty, Olympian spirit—in an everyday domestic setting, in the apartment he shares with his mother Susanna (Adriana Asti) and his cousin Graziella Chiarcossi (Giada Colagrande), who seems to perform the functions of both housekeeper and secretary. It’s a pleasure to see the maestro doing something as mundane as choosing his shirt for the day, although it’s apparent that even when he’s there he’s not entirely there, frowningly sinking into his newspaper rather than engaging much with his family. And it’s certainly a pleasure to see the veteran Asti—who appeared in Pasolini’s Accattone (1961) and was the idolized young aunt in Bertolucci’s Before the Revolution—with her eyes like brilliant black beads undimmed at 83, her age when Ferrara’s film was made; Susanna’s grief on learning of her son’s death is painfully trenchant, the film’s one true release of emotion, at least before the brutal climax.

Equally pleasurable in these scenes is when Maria de Medeiros sweeps in with outrageous panache as Pasolini regular Laura Betti, waving a ludicrously extended cigarette holder, wearing a huge bobbed blonde wig, and regaling the family with ripely scabrous comments about the Yugoslavian actresses she encountered on the set of Miklós Jancsó’s Private Vices and Public Virtues (where, she jubilates, she got to direct the orgy scenes herself).

These glimpses of the private life serve partly as a frame for dramatized sequences of Pasolini’s lesser-known work. We see him at his typewriter—the Olivetti poignantly shown in close-up in the film’s final shots—working on a new piece of literary fiction that is less a novel, he says, than a parable. One of the dramatized sequences—based on Petrolio, the uncompleted political novel that was published posthumously in 1992—involves Pasolini’s apparent alter ego Carlo (Roberto Zibetti), a protagonist he nevertheless describes as “repugnant to me,” attending a high-society reception where the overheard talk around him is all about the oil trade, banks, the Vatican, bombings, and on-and-off Italian premier Giulio Andreotti. In a private salon, a bearded, magus-like man tells a story about an ill-fated flight to Cape Town and a moment of truth among the rose-colored sands of the Sudan—at which point, Ferrara tosses in a macabre visual image so ludicrously kitsch that the film very nearly loses all the credit that it’s won till then.

We also get the intermittent reconstruction of Porno-Teo-Kolossal, in which the real Davoli plays an affable holy fool figure named Epifanio ( “Epiphany”) who hears murmurings that the Messiah is coming, and decides to follow the annunciatory star in the sky, having spotted it while taking a piss; he later takes another piss on the stairway to heaven, the kind of cheerfully irreverent act that Davoli was born to. Epifanio and his young cousin (also played by Scamarcio) travel by train to Sodom—“the most free city in the world . . . the city of lesbians and gays.” There they’re taken to witness the “Feast of Fertility,” the annual event at which, for one night a year, men and women have sex for the purpose of procreation. For a moment, Ferrara catches something of the anarchic explosive sexuality of Pasolini’s ’70s ‘Trilogy of Life’ ( The Decameron, The Canterbury Tales, The Arabian Nights)—although notably he does it with heterosexual sex in a raucous mode, as fireworks explode and the assembled throng chants “Vaffanculo!” from the side.

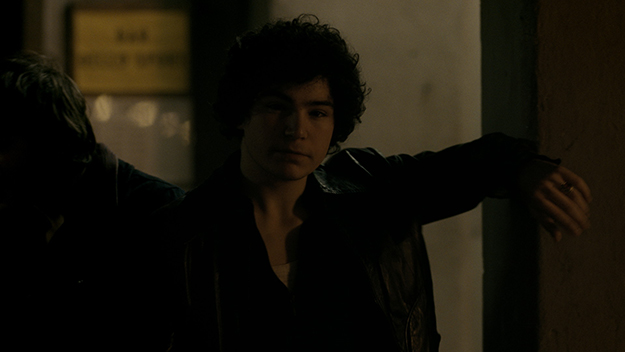

While Ferrara invests considerable energy in this sequence of male-female action, there’s a feeling of clichéd awkwardness about Pasolini’s gay activities, associated here strictly with the night and with danger. You can take Ferrara out of New York (he’s been based in Italy for several years now), but you can’t take New York and its mythology out of Ferrara, and in the scenes where Pasolini cruises Rome at night, appraising its curly-haired leather boys, he couldn’t resist placing posters of Lou Reed (from the Transformer sleeve)—partly, no doubt, as a tribute to the recently dead singer, but perhaps also as a convenient signpost to the kind of nighthawkery we’re dealing with here.

This strand leads us straight to Pasolini’s death at the end of the film—a murder that has been the subject of much controversy and political speculation. In Ferrara’s version, tying in with Pino Pelosi’s later statements, the youth is not the killer per se but a bystander—although he’s presented here as a troublingly complicit one, perhaps tied up from the start with the men who brutalize Pasolini, although there’s no direct suggestion that they’re acting specifically from political motives. The sequence, partly filmed from above in a crane shot, is staged as Pasolini’s own Passion—a moment of approaching sexual rapture, then one of violent agony. In terms of what we see, this could just be a viciously mundane gay-bashing. In terms of the film’s overall logic, however, what’s suggested is the sexual and political martyrdom of a man punished by society for the threat that he poses with his statements on paper and film and his increasingly severe media pronouncements.

Through all the strange jumble of incident and texture that makes up the film, and Ferrara’s odd choices (why does Pasolini drive around to “Polk Salad Annie,” of all things?), this is perhaps the theme that emerges most coherently: a nostalgia for a bygone age when scandalizing was an activity that mattered; not just a right, but for some, a dangerous calling. As a tribute, Ferrara’s Pasolini is sincere, even scholarly; as a film, it feels too stilted and reverent to capture much of that sense of danger.

Jonathan Romney is a contributing editor to Film Comment and writes its Film of the Week column. He is a member of the London Film Critics Circle.