Film of the Week: Out 1

Jacques Rivette’s Out 1 is one of the legendary “impossible objects” of modern cinema, and for a long time was one of the great (almost) unseen films. The result of six weeks’ shooting and six months’ editing, it was originally shown only once, in a work print, in Le Havre in September 1971 (reputedly, the projector broke down). It later resurfaced in the late Eighties and early Nineties, and has even become available on DVD, but there’s no substitute for immersing yourself in a big-screen projection, which is now possible thanks to the film’s restoration.

It’s worth defining exactly what Out 1 is and isn’t. Sometimes known as Out 1: Noli Me Tangere (although the subtitle never appears in the credits), this is an eight-episode, 773-minute fiction film; it was originally intended as a TV serial, but was turned down by French broadcaster ORTF. It shouldn’t be confused with Rivette’s later four-hour re-edit of some of the same narrative material, under the title Out 1: Spectre (so called, apparently, because that film was a sort of “ghost” of Noli Me Tangere, which means “touch me not”). And while the complete Noli Me Tangere was never actually a TV serial, it has the shape of one: it arguably offers the first-ever case of a “Previously on…” sequence, with each episode (starting with the second) prefaced by a series of black-and-white stills from the preceding episode.

Prospective viewers hoping to lose themselves in the drift, the immensity, of Out 1 should be warned of Rivette’s original intention, as he told Le Monde in 1971, to make a film that would “function like a bad dream . . . one of those dreams that seem all the more interminable because you more or less know that’s it’s a dream.” Out 1, given the vaguely hippie-ish milieu it is set in, could also be called a bad trip, not just because of its hallucinatory bending of time and causality, but because of its rueful melancholy; it’s a story about things, people, and communal causes falling apart, arguably a lament for France’s failed utopia of 1968.

There was never a script, more a kind of “chart” of possibilities, with coherence supervised by Suzanne Schiffman, credited as co-writer. No stranger to improvisation—notably in the two films that came either side of Out 1, L’Amour Fou and Céline and Julie Go Boating—Rivette gave his actors freer rein than he did elsewhere, allowing them to create their own characters and stories. It was the very personality of the actors that generated these possibilities. For example, Schiffman persuaded Rivette that Jean-Pierre Léaud wouldn’t excel at improvising, that he needed an instrument and a text to work with: thus, his character Colin ends up playing the harmonica and trying to decipher scraps of paper that seem to be encrypted with references to Balzac and Lewis Carroll.

The film plays out between two communities: two theater groups led respectively by Lili (Michèle Moretti) and Thomas (Michael Lonsdale), both attempting to rehearse Aeschylus plays. Both companies seem, however, to have thrown their texts away and instead practice a very Sixties form of freak-out exercise, influenced by the likes of Peter Brook, Jerzy Grotowski, and possibly, in Thomas’s case, a Bacchic touch of Viennese Actionism. Some of the theater sequences last as long as 40 minutes, and to be honest, whenever I’ve revisited Out 1 on DVD, these are the parts I’ve skipped; but, for the sake of the whole durational thrust of the film, you should be prepared to live through them once.

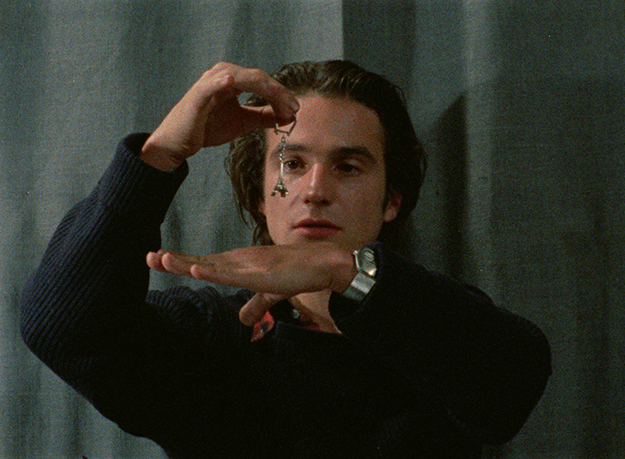

More intriguing, and providing the real spine of the film, are the parallel investigations of two eccentric loners (both of them defined as “out,” excluded from the social circuits they investigate). There’s Colin (Léaud), originally billed as “the deaf-mute,” although he eventually starts talking; he’s first encountered wandering round cafés offering customers a “message of destiny” and blasting them with tuneless harmonica, with the blank-faced aggression of Harpo Marx (possibly a joke about Bob Dylan’s own reedy blasts being taken as oracular broadcasts).

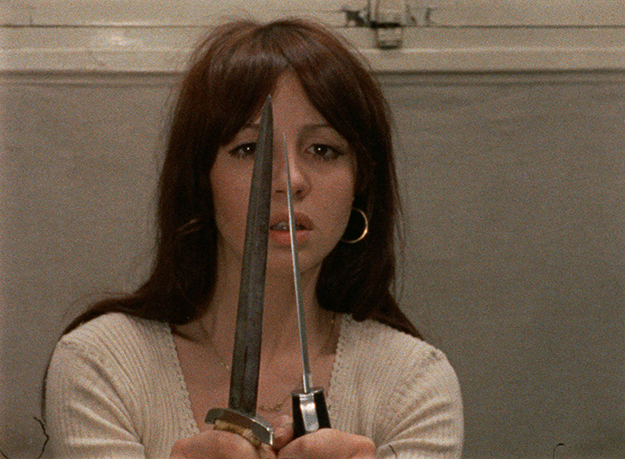

The other loner is Frédérique, played by Juliet Berto: a piratical, gypsyish, sexy yet oddly child-like grifter and petty thief, who—if you’re inclined to read Out 1 this way—might be dreaming the whole thing up in her lonely attic room, “writing” the intrigue from her end of the detective work just as Colin is writing it by decrypting the mysterious sheets of paper he has been given. Frédérique’s route leads her through the Paris underworld; Colin’s leads him through an “underworld” of arcane meaning, seemingly to be deciphered by reference to Lewis Carroll’s The Hunting of the Snark and Balzac’s vast novel cycle the “Human Comedy.”

The slender thread that both outsiders follow has to do with a supposed “Thirteen,” a secret conspiracy evoked by Balzac in three novellas (one of which, The Duchess of Langeais, Rivette later adapted as Don’t Touch the Axe, in 2007). Certain characters in Out 1 appear to be members of a modern-day Thirteen, although they turn out to be neither terribly sinister nor very formal as an organization—more a vague grouping of friends knitted together by interpersonal intrigues and fallings-out. The two sleuths’ independent investigations simply serve, on one level, to bring them into contact with assorted characters, sometimes in episodes which connect with the plot, sometimes in stand-alone encounters. Frédérique certainly has many of the latter, not always quest-connected, and one of the film’s great joys is Berto’s skittish duets with figures including Jean-François Stévenin (also the film’s AD) as a sub–Wild Ones biker who turns nasty on her; a pair of comic pornographers (one played by film historian Bernard Eisenschitz); and Honeymoon (Michel Berto), a rueful middle-aged man whose unrequited love for a young Adonis later threads its way into the story, bringing the whole a certain unexpected closure of sorts.* As for the French literary subtext, Eric Rohmer—very funny and nervy as a desiccated Balzac specialist—turns up as Colin’s advisor on the Thirteen, his words serving to notify us that the very idea of a conspiracy can be patently no more than a device to create an impression of order and design beneath chaos and contingency.

Perhaps the closest thing to Out 1 in 20th-century French literature is André Gide’s hugely self-reflexive experimental novel of 1925, The Counterfeiters, also built on the premise of a conspiracy. The novel explores the possibility that a novel might be driven by the autonomy of its characters, who develop according to their own rhythms and drives, and sometimes exert a fascination on the author that he might not be able to account for or control. In the book’s last sentence, the novelist character Édouard says he’s curious about a marginal character called Caloub—who just happens to have been mentioned in passing on the very first page. So the novel loops back on itself, Möbius-style. By the same token, the final shot of Out 1 is of Marie (Hermine Karagheuz), a member of Lili’s troupe, whom we’ve barely paid attention to so far—except that she, mysteriously, was the very person who started the narrative ball rolling by placing a message in Colin’s hand. Is she about to plant another communication (and thereby perhaps instigate the Out 2 that Rivette once planned)? Or is the final image as seemingly arbitrary as all the Parisian street shots that appear throughout the film? To quote the title of another Rivette film, Va Savoir—“go figure.”

What forcefully asserts itself in this final shot, however, is the pre-eminence of the arbitrary: we know that the film could have ended with a shot of any other character. The contingent, the unforeseeable and uncontrollable, is a privileged element in much 20th-century experimental art—in music and painting as much as in film and literature—and Out 1 honors it to the maximum. But giving actors their head as much as Rivette does here brings a particular urgency to the idea of fictional characters controlling their own fates: here, the characters genuinely emerge as a result of the performances evolving in particular ways.

The most extraordinary example of that is the case of Sarah (Bernadette Lafont), a writer enlisted by Thomas to help bring new life to his production. Sarah hovers on the fringes of the action for a long time, seemingly benign and unfocused. By the final two episodes, however, she has become something else, an apparently sinister, foreboding presence who, without warning, starts speaking backwards on the soundtrack—an eerie touch of Twin Peaks years avant la lettre. The final episode features a long scene between Sarah and Emilie (Bulle Ogier), sitting on a bed together, speaking seemingly inconsequential dialogue spiked with repetitions: “Why are you looking at me like that”, “Why don’t you go to bed?” But the scene becomes intensely ominous and troubling, partly because it’s largely shot in a mirror, to eerily distancing effect, partly also because of Lafont’s impassive sotto voce delivery and implacable blank stare—performance effects that profoundly inflect the scene in a way that couldn’t possibly have been predicted, either by script or by direction.

Mirrors, in fact, become increasingly evident in Out 1, and in this final episode, two mirrors facing each other on opposite walls create a visual effect that suggest the fiction potentially spiraling off into infinite parallel dimensions. Out 1 may be very much a film of its time, but it has a peculiar currency now, in that today’s mainstream storytelling media, increasingly over the last decade, have become very much fixated on the possibilities of infinite narrative expansion: comic-book series that can spin off new hordes of characters, initially discrete movie fictions that can be rebooted over and over again, TV series that can be spun out regardless of coherence to keep a good thing going as long as is profitable.

But there are more serious versions of this dream of narrative elasticity and variety. Out 1 has literary and theoretical affinities both with Jorge Luis Borges’s story “The Garden of Forking Paths” (about a fiction that can theoretically accommodate all contingencies) and with Julio Cortázar’s 1963 novel Hopscotch, which invites readers to plot their own zigzag course between chapters; more recently, Out 1 finds echoes in the populous and very non-linear longer novels of Roberto Bolaño. As for cinema, the filmmaker currently following Out 1’s principle of contingency to audacious extremes is Lav Diaz, whose (usually hyper-extended) fictions genuinely follow the lead of their actors: if one player chooses to leave, or happens to go to prison, Diaz simply lets their character drop out of the action, and follows whatever new path emerges as a result. Watching Out 1 today, you certainly don’t feel that its adventure, like so much Sixties experimentation, leads towards a glorious but quixotic blind alley; it’s still one of the most artistically exciting films you’ll see. In all kinds of new ways that might not have been apparent even 10 years ago, it feels strangely close to us today.

* Honeymoon is, incidentally, the only gay male character I can think of in the Nouvelle Vague canon—unless I’m missing some in Chabrol, perhaps?