Film of the Week: Long Day’s Journey Into Night

All images from Long Day’s Journey Into Night (Bi Gan, 2018)

The two features of Chinese director Bi Gan are haunted by echoes and eerie recurrences: tunnels, water, clocks and watches (broken, or drawn as child-like images on walls and wrists); cars, motorbikes and trains; apples and a grapefruit-like citrus fruit called a pomelo. Rewatching Bi’s second feature Long Day’s Journey into Night, I struggled as much as on first viewing to piece together the plot, if it really is a plot. But this is a film that makes less sense in terms of who people are and what they do than in terms of the way specific objects and images turn up, and how they’re filmed.

Long Day’s Journey Into Night is unmistakably the work of the director who made his fiction debut with Kaili Blues in 2015, although it’s also more derivative, in the sense of being packed with echoes of other movies. Kaili Blues wasn’t—at least not obviously. It was a film of striking individuality and waywardness: one of those works that make you realize exactly what filmmakers mean when they talk about formal freedom. That film was rooted in realism, and in the cultural and geographic specificity of Bi’s home region, the subtropical southwestern province of Guizhou. But Kaili Blues also gave itself free rein to vault at will desired into the realm of dream, to absolutely follow its own nose in its exploration of space. Its most virtuoso passage was a 40-minute single take which followed the film’s doctor protagonist on various vehicles to a riverside village, then sidetracked as if on a whim to follow a new character, a young woman in a yellow skirt as she crossed the river by boat, then walked back to her point of departure. At one point, just as the camera is following the doctor’s motorbike down a hill, it suddenly veers on a detour down a flight of stairs to rejoin him at the bottom—because why not?

Something of the same lawlessness prevails in Long Day’s Journey Into Night although it’s a much more elaborately contrived film, bound by very precise and consistent control. It also pushes the dream dimension of Kaili Blues much further to become the entire substance of the film—so much so that it becomes moot whether anything we see is actually real at all. All we know is that it’s the stuff of cinema—which is to say, such stuff that dreams are made on. At one point, taciturn hero Luo Hongwu (Huang Jue) muses in voiceover on the difference between film and memory: films are always fake, he says, whereas memories are made of truth and lies. It’s hard to know what that makes dreams: perhaps a specialized kind of cinema that’s closer to truth because it’s so intensely composed of memory.

Long Day’s Journey Into Night is ostensibly about a man who returns to his hometown of Kaili after his father dies, to find himself musing on the past and trying to retrieve its traces. Haunting him—as a memory but also perhaps as a ghost—is Wildcat, a friend from his youth, found dead down a mine after getting on the wrong side of Zao, a gangster. Also refusing to let go of Luo Hongwu is a woman (Tang Wai, from Lust, Caution) he once hoped would help him find Zao. Her name, she tells him, is Wan Qiwen. “Sounds like a pop star name,” Luo says, and certainly she’s more vivid than life: a sultry, sullen film noir vamp in a dark green silk dress. Much later, she seems to have taken another name and disappeared: it’s as if Luo isn’t just pursuing Wan Qiwen, but a whole series of different women (including the memory of his dead mother), who may or may not be all versions of the same one.

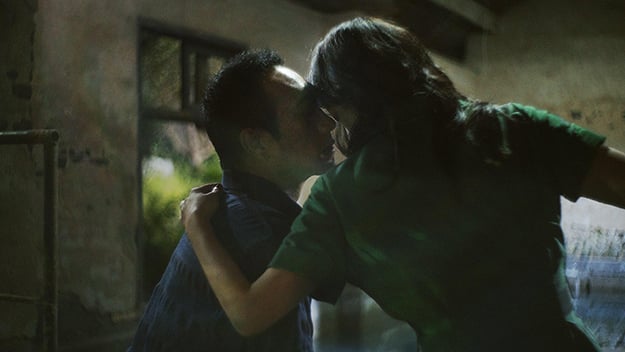

Needless to say, Luo—seen skipping between his present and past selves so fluidly that we cease to notice the difference—starts an affair with Wan Qiwen, albeit of a stylized, idealized, somewhat decorously torrid kind. They’re seen sharing an upside-down kiss while lying by the side of a pool of water, the camera tilting down to explore its green depths, filled with foliage and what may be a broken clock; later, their heads are lit with the same dark emerald color as her dress. The film is steeped in neon and residues—colors and gestures—of the collective memory of paperback thrillers. There’s a wonderful sequence that offers a shamelessly fetishistic image of Wan Qiwen’s feet as she playfully trips along a brick wall. Even people who swooned their way through the gorgeously styled retro-romance of In the Mood for Love may find Bi’s film a little ripe.

There’s certainly a lot of Wong Kai Wai here, not least in the constant ducking in and out of the labyrinth of memory and storytelling: in a bottomless regress, characters often recall things that other characters once told them long ago, in conversations or letters. Wong’s influence can be felt in the existential economy of the characterizations: handsome man on a hunt, beautiful lost vamp, malign heavy in a fedora… But there are so many stylistic reflections that the film is as vertiginous as a hall of mirrors (and let’s not forget Vertigo, either). Bi Gan loves water and ruins as much as Tarkovsky and Tsai Ming-Liang: he even has water trickling down the wall of a prison room when Luo is interviewing a woman through a beehive-pattern grille, part of a thread of honey references. The lavish neon is very 1980s, with one shot of a street market suggesting that this Chinese director is riffing on a canonical Western fantasy of Asia: Blade Runner. More than anything else, I found myself reminded of the luscious early-’80s effusions of the cinéma du look, of Carax and Beineix (notably the latter’s florid, much-maligned The Moon in the Gutter).

The abandonment of narrative transparency in favor of the associative, constantly switchbacking logic of dream is also very reminiscent of Raúl Ruiz, although where his oneiric movies were always overtly artificed, Long Day’s Journey Into Night, for all its stylization, always conveys the effect of a natural free-associative flow. There are multiple literary allusions, too: as Dennis Lim noted in his Film Comment feature last year, Bi Gan has acknowledged the influence of writers like Patrick Modiano (the Nobel-winning French bard of fugitive memory) and Roberto Bolaño, notable for his absolute liberty with form (the Chinese title of Long Day’s Journey Into Night is Last Evenings on Earth, after a Bolaño collection).

Just over an hour in, Long Day’s Journey Into Night becomes, not a different film exactly, but the same film in a different register: it jumps into 3-D. Wiling away time on the search for Wan Qiwen, Luo enters a run-down cinema and dons a pair of 3-D goggles—at which point, we’re invited to don a pair too and enter the film he’s watching, which seems to be called Long Day’s Journey into Night.

The following hour is again a single traveling shot—rather than “tracking shot,” which would suggest a process shackled to the ground by heavy rails. No, this shot travels—along flat ground, through the air (twice, in entirely separate and miraculous ways), up and down the stairs of a ruined fortress that might have been designed by Escher or Piranesi. It travels so seamlessly that you simply let yourself be carried along in wonder, as Luo himself is carried along within the movie—on a mining trolley, a motorbike, a cable car and on foot in the wake of two mystery women (one played by Sylvia Chang in a red wig and carrying a blazing torch) who may be nocturnal twins of women from the real world.

This hour, if you have the chance to view it properly in 3-D, is as immersive an experience as any big-budget Hollywood production (Bi Gan is known to be an admirer of Gravity) and is as close as 3-D comes to the aspirations of virtual reality in the sense of seeming to pull you weightlessly yet quasi-physically into the space of the screen. Here it’s to do partly with the canny deployment of space on multiple levels (we’re forever floating downwards, surging up again), partly to do with the way that surreal non-sequiturs take on a matter-of-fact autonomy (mine tunnels turn into a mountain road, a boy wearing a cattle skull announces himself to be a ghost), partly through deliriously beautiful mise en scène, like pastel-colored carnival lights seen from high on a hill at night (the three DPs include Dong Jinsong from Black Coal, Thin Ice and David Chizallet, the French cinematographer of Mustang). There’s also the use of silence, sound, music: whistling wind, pop balladry on a village PA, an eerie distant choral chanting that you may find haunting your own dreams afterwards (if you’re lucky enough to have them fully wired for sound).

Certain elements will be elusive for non-Chinese viewers, notably local references and use of Guizhou dialect, the names of certain characters (why exactly does Wan Qiwen sound like a pop star’s name?) and possibly some symbolic allusions, like the wild pomelo that Wan demands as part of her deal with Luo). None of this really matters, as Long Day’s Journey Into Night is an all-enveloping experience that genuinely approaches the condition of hallucination: one steeped both in anxiety and in rapturous eroticism.

This may make the film something of an anomaly today. In a politically fraught era, movies that cast a spell, that envelop us in a state of imaginative otherness, rather than giving us solid information about or somehow reinforcing our engagement with the concrete world, are often held to be trivial, irrelevant (unless those films are fantasies backed with multi-million-dollar budgets, in which case they’re generally held to be part of the political real and thus worthy of attention). Yes, Long Day’s Journey Into Night could easily be dismissed as mere poetry—but when it comes to poetry this imaginatively spellbinding, there’s no “mere” about it.

Jonathan Romney is a contributing editor to Film Comment and writes its Film of the Week column. He is a member of the London Film Critics Circle.