Film of the Week: “I Do Not Care If We Go Down in History as Barbarians”

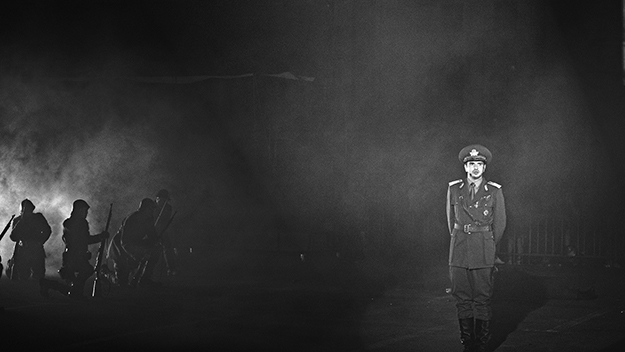

Images from “I Do Not Care If We Go Down in History as Barbarians” (Radu Jude, 2019)

Radu Jude was one of the first directors of the Romanian New Wave to stray from the austere visual realism that seemed to have become the default mode for that country’s reinvented national cinema. Aferim! (2015) was a black-and-white 19th-century epic with a visual style somewhere between Miklós Jancsó and Sergio Leone, while the ’30s-set Scarred Hearts (2016) used tableau-style compositions to depict life in a sanatorium, with striking use of horizontality to reflect the fact that its hero spent much of his time lying immobile with his chest in a plaster cast. These two films established Jude as one of the most intriguing stylistic experimenters in contemporary Euro-fiction. But his latest work steps away from such visual invention; it’s unadorned, but pugnaciously challenging in other ways. The film’s confrontational stance begins with its title,“I Do Not Care If We Go Down in History as Barbarians.” The quotation is from Marshal Ion Antonescu, Romania’s dictator—or self-styled “Conducător”—from 1940 to 1944. Tried and executed for war crimes in 1946, Antonescu was the head of a nation that, although eventually fought against Germany, did so only after initially collaborating with it. Romania’s history of anti-semitism in the ’30s and ’40s was the subject of Jude’s last feature, the extraordinary archive documentary The Dead Nation (2017); he now pursues the theme very differently in “I Do Not Care…”.

The central fact of the film is the Odessa massacre of October 1941, following Antonescu’s orders to execute the Bessarabian Jews of the city, then under Romanian control, resulting in up to 34,000 deaths. The heroine of Jude’s film is Mariana Marin (Iona Iacob)—not to be confused with the poet of the same name, Iacob herself announces at the start. Marin is directing a live project to be staged outdoors in Bucharest—a “stylized, compressed, theatrical” reenactment of the massacre. Early on, we see Marin auditioning non-professionals for her cast. Some are people who seem to have wandered in by chance, others dedicated war reenactment buffs, not all of whom approve of her using reenactment to “subversive” effect, as she puts it: they want their idea of authenticity, bloodshed, fire, and all. We also see Marin at home, reading aloud texts related to her subject—including a commentary about a letter by Hannah Arendt and a lengthy passage from the Russian writer Isaac Babel on his experience of the Polish-Soviet War of 1920. In a subplot, she’s seen with her boyfriend (Serban Pavlu), a married airline pilot by whom she may be pregnant.

She’s also seen—in a sequence lasting some 17 minutes in long takes—discussing the nature of truth as related to national history with a man named Movila (Alexandru Dabija). He represents the municipal body that has greenlit her project, and which can pull the plug at any moment. This section of the film is essentially a philosophical debate between the two characters. Marin has a clear idea of the historical truth that she wishes to expose in her project; opposing her idealism and sense of purpose, Movila puts forward a skeptical, even cynical relativist case that borders on outright denial of the nation’s past. The fact that he’s an affable member of a literate liberal intelligentsia is what makes him all the more troubling an opponent. He’s able to meet Marin on her intellectual ground and bring his own reading to bear (“I’ll raise you Richard Rorty and Thomas Kuhn,” as the subtitle puts it). Movila begins, like any cautious producer worried about alienating the public, by insisting that Marin’s show shouldn’t scare children; before long, he’s questioning the very basis of her project. What good does it do to alert people to the existence of atrocities in the past when they go on happening regardless? Events are “historical,” he says, only because historians write about them; he is voicing an increasingly common view in a world that is ceasing to care about experts or about verifiable truth (and in which even one of Marin’s hip female friends can look at German troops in a newsreel and comment admiringly on their elegance).

A passing joke about Alain Resnais’ Hiroshima Mon Amour (1959) is one of the more accessible references in a densely allusive, extremely erudite film. Assorted historical and cultural figures are cited, among them E.M. Cioran, Mircea Eliade, and the late Lucian Pintilie, who before the New Wave was Romanian cinema’s most internationally visible name. A recurrent reference is to Sergiu Nicolaescu, the director of historical dramas. One of his films turns up on Marin’s TV: entitled The Mirror (1993), it is effectively an apologia for Antonescu, who is depicted as an altogether noble figure at his trial. “Imagine that in Germany,” Marin sourly comments, “Films on TV paying homage to Hitler.”

For much of the time, Jude directly addresses the business of filmmaking—or at least, the creation of visual spectacle, since Marin isn’t a filmmaker per se—and the ways in which recreating the past can obscure history’s meaning as one gets caught up in the making of illusion. Marin is seen with a sound designer who plays her a series of different gunshot sounds, some authentic for the period, others more expressive dramatically: a context in which instruments of death simply become effects. We also see much archive newsreel, on film (played on a Steenbeck), TVs, and laptops. At one point, Marin considers using footage of wartime shootings and burials in Lithuania: it looks right and besides, there is a dearth of film showing the actual events that concern her. But this footage is similarly becoming just usable material; it’s only too easy to forget that we’re watching images of murder.

Amid this dense battery of historical and cultural argumentation is some pithy comedy, all the more slippery as it’s couched in the self-conscious framing of Jude’s film. At the start, its lead introduces herself to camera as Ioana Iacob, tells us that she’s playing a character called Mariana Marin, and then strides off, rifle slung over her shoulder, with a cheery “Enjoy the film!” (We also see a clapperboard with Jude’s name on it). From this point on, we’re aware that we’re watching a self-reflexive demonstration-by-masquerade, with everyone playing a part. The amateurs that Marin recruits for her cast are a raggle-taggle bunch of all shapes, sizes, and ages—an elderly woman who puts on a display of anguish, comparing her own performance to Mrs. Ceaușescu on trial, and assorted musclemen, beer-bellied burghers, and wild-eyed youths who join up to play soldiers. Significantly, a quarter of Marin’s recruits enthusiastically volunteer to be Germans, and some express outrage that Gypsies are taking part in the performance (Aferim! was very much about the historical mistreatment of Gypsies in Romania).

The first part of the film largely takes place in and around Bucharest’s National Military Museum, its gardens filled with tanks and other battle vehicles. The film becomes truly disturbing when the action shifts to a city square, where the performance is staged at night.The format also shifts from 16mm to DV, as if Jude is now shooting an actual non-fictional event, docu-style: in a sense he is, since this performance actually happened in a Bucharest square, staged for the film. Marin’s show is a kitsch display, with spectacular video projections, a brass band in white regalia, and various actors, including one playing a speechifying Antonescu. It’s hard to define, though, exactly what kind of show Marin thinks she’s mounting: whether it’s the sort of reenactment as performance art that has been undertaken by political artists such as Jeremy Deller (e.g. his recreation of the Battle of Orgreave, the 1984 confrontation between British police and striking miners) or a piece of municipally-funded civic entertainment, which she has perhaps ended up staging unwittingly.

What’s truly horrifying, apart from the show’s content, is the response of the audience gathered in the square. When the German army march on with swastika banners, people happily clap along to the brass band—then boo when the facsimile Russians appear. They also cheer when an actor playing a priest spouts virulent condemnations of the Jews. But here’s the question: did a real audience actually cheer? Are the audience members themselves extras playing the public in Jude’s film, and if so, were they instructed to cheer (or indeed, was the cheering added in post-production)? Or conversely, are these real citizens of Bucharest who turned up for the show and spontaneously showed their true colors? Can we conclude that, in staging this nightmarish spectacle for his cameras, Jude has effectively pranked the Romanian public into exposing its darkest convictions?

That element of uncertainty is the film’s most interesting and troubling aspect. In other ways, “I Don’t Care…” is awkwardly on-the-nose in making its points—and arguably too cluttered with specific references to communicate easily with non-Romanian viewers, who won’t have heard of Sergiu Nicolaescu and won’t get the joke (as I confess I don’t) about Marin sharing her name with a poet. Yet Jude’s point seems to be that, given the cultural blindness and short memory he’s critiquing, most Romanian viewers won’t get it either, or even care. That’s why Marin—constantly dropping historical and philosophical references in front of her baffled cast—is effectively shouting into the void. Jude, using her as his surrogate, is concerned that he may be doing the same. Indeed, it’s constantly evident that Marin’s didactic venture may be futile or even counter-productive—simply contributing more bombastic spectacle to the world, exemplifying the tendency towards the “pageantization” of history, defusing and obscuring the real meaning of the past. The show may even, for its audience, end up legitimizing or fueling anti-semitic feelings.

Jude’s self-reflexive, agonized attempt to evoke history—while musing on the dangers of uncritical historical reconstruction—reminds me in some ways of Atom Egoyan’s flawed but bracingly complex Ararat, which focused on the much-denied realities of the Armenian genocide and on the contradictions inherent in trying to make a realist movie about the subject. “I Don’t Care…” is at once more playful and more intense, denying us the lush imagistic pleasures of Egoyan’s film, instead offering a caustic, sometimes farcical humor that channels its maker’s rage. The general tone, however, is closer to early ’80s Godard films such as Sauve Qui Peut (La Vie) (“Every Man for Himself, ” 1980) or Passion (1980), another film about the problem of making images that may be realistic, as opposed to true. Ioana Iacob, with her punchy, boomy voice and general don’t-give-a-fuck demeanor, makes a genially arresting center to the chaos as the beleaguered intellectual heroine who’s also a natural clown. There’s a lovely comic moment when Marin and a gaggle of helmeted mock-militia huddle under a table to shelter from a rain shower. It might just be a goofy sight gag, yet it reminds us that you can hide from the weather but you can’t hide from history.

Jonathan Romney is a contributing editor to Film Comment and writes its Film of the Week column. He is a member of the London Film Critics Circle.