Film of the Week: Erased,___Ascent of the Invisible

All images from Erased,___Ascent of the Invisible (Ghassan Halwani, 2018)

Digital technology has made it possible to cleanly and imperceptibly erase any aspect of a still or moving image that you don’t want to be seen—wires in an action movie, blemishes on an actor’s face, Kevin Spacey. Ghassan Halwani’s Erased,___Ascent of the Invisible—screening in FSLC’s Art of the Real on Saturday April 27—is not specifically concerned with the now routine matter of digital-age erasure, but at a time when it’s increasingly hard to believe in the fidelity of images to any original truth, this film makes us acutely aware of what erasure can entail, politically and philosophically, and what it might mean to attempt to counteract its effects.

This fascinating hybrid piece by the Lebanese filmmaker, animator, and artist could be called a speculative documentary, an essay film, a conceptual art piece, or any combination of the above. Early in the film, the screen is filled with a seemingly innocuous black-and-white photo showing a nondescript patch of yard between walls. But as we look, we start to notice incongruous elements. Something resembling a hat hovers strangely in mid-air at head height, offering something of the same uncanny incongruity as the stretched skull in Holbein’s painting The Ambassadors. And there’s a curious blur in the air, like a heat haze, as if one or more human figures had almost, but not quite, dematerialized. That’s exactly what has happened. Halwani has altered the photo to erase a group of human figures, leaving only traces: the hat, a shoe, the blurry patch where their bodies were and, strangest of all, a slogan from a T-shirt that, with the shirt and its wearer erased, now becomes a piece of graffiti on the back wall (“I Gave My Best Shots” [sic]).

Talking off screen with the man who took the photo, Halwani establishes what the picture originally showed: a man being kidnapped by two militiamen during the Lebanese civil war, specifically around the time of the Sabra and Chatila massacre of 1982. Tantalizingly and troublingly, Halwani shows the photographer the original picture, and the man describes what he witnessed back then—a hostage with a bag over his head, the gun one of his captors carried. But we’re not allowed to see the original: our imagination, fueled by the photographer’s memory, has to do the work.

His treatment of the photo is one of several devices that Halwani uses in two ways. One is to make us consider the phenomenon of erasure, and what it might mean when applied to people and the historical events they are caught up in. The other is to attempt to revive, if only for a moment, people whose memories, faces, and names have been lost in the fog of history (or rather, non-history, since their disappearances were never recorded). Some 17,000 Lebanese citizens disappeared during that conflict, Halwani tells us—although we also hear an official insisting that the number was only two thousand or so. Halwani doesn’t want these people to be forgotten, and finds methods of symbolically bringing back to life some of the disappeared.

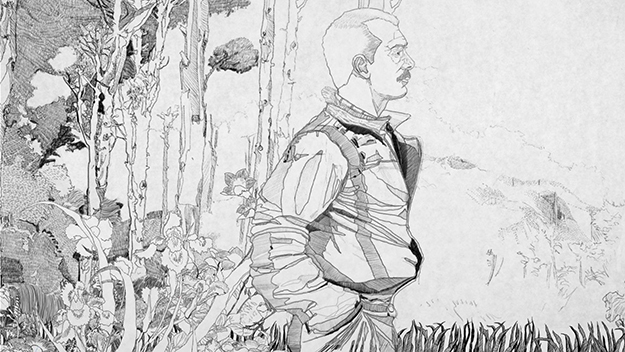

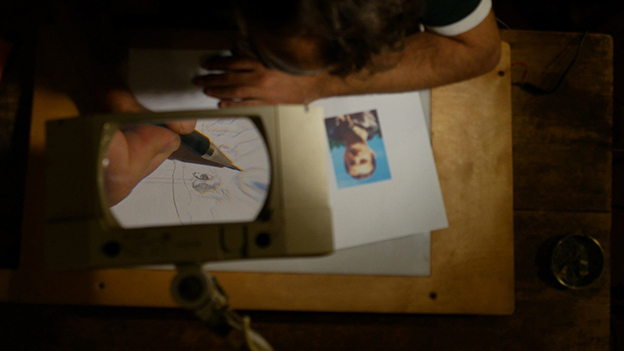

In one sequence, we see him painstakingly cutting out the likenesses of individuals from a grid of pictures that collate a lost multitude. Lost in this collective portrait, he points out, these people lose their individual being, become purely part of a system of symbols: he intends to make some of these people real again. With methodical attention and patience, he turns their photos into line drawings, then gives them dimension by extrapolating from these frontal pictures into reconstructions of his subjects in profile. Those images then become animations. A man referred to in the English titles as “George” is seen standing windblown among waving foliage, mustachioed and in a flak jacket, and with added color, to reconstruct the moment long ago when George was photographed outdoors.

Another of Halwani’s methods comes across like a supremely patient act of performance art. He is seen slicing with a scalpel-like art knife at a wall of posters, trimming away ads for theater shows and dance nights to uncover images of faces underneath. Sometimes a whole face will appear through gaps, sometimes just a pair of eyes; he also unearths written captions in Arabic (“It is in our memory that she lives on”). Where the paper won’t peel off, he applies a paintbrush steeped in water, a delicate process of erosion that causes the faces underneath to slowly materialize, like pale ghosts. We also see him adding numbered captions: restoring names to these long-forgotten faces.

Erased… offers some fascinating thoughts on the question of memorialization and of the official function of forgetting, when that serves a regime better than true remembering. A key site that fascinates Halwani is Beirut’s vast Normandy garbage dump, where many bags of human bones were unearthed: officials, however, have insisted that that they were animal bones, or even that they were from the 17th century, contradicting forensic evidence. We see footage scanning the surface of this massive site—and what could be a more concrete trace of human presence than a garbage dump? It turns out, however, that the Normandy dump itself has been erased and built on. It has been “rebranded,” as the English caption tells us (the word redolent of a corporate-style rewriting of history) as Beirut’s prestigious “New Waterfront District.” The district is the location for a memorial to the dead of the civil war—to its “martyrs,” as they’re officially termed. But, as Halwani points out in a voiceover conversation with a brigadier-general who pushes the official line, commemorating the disappeared as nameless martyrs only serves to erase them once again: the Normandy dump bore witness to their ordeal, but that witness is itself now eliminated.

Another briefly glimpsed set of images, seen from above as Halwani studies them at his desk, comprises a book of photos (or possibly hyper-realistic drawings) of the sometimes damaged personal effects of nameless individuals: glasses, combs, watches. They are never explained, but these are presumably things left behind by people abducted or killed, in Lebanon or elsewhere. You inescapably think of the personal effects left behind by the dead of the World War Two camps; or of Patricio Guzman’s documentaries (Nostalgia for the Light, The Pearl Button) and the Chileans searching in the Atacama Desert for remains of their relatives (sometimes just fragments of bone) who disappeared in the Pinochet years.

As Halwani puts it in another of his (sometimes confusingly phrased) English captions, a crime is committed in two acts: one is the act of killing, but the other is the hiding of the crime, the denial that it ever took place. The most disturbing revelation of Halwani’s film is that the disappeared of Lebanon are not officially dead—have never been allowed to die. While their relatives and descendants may have later passed away and been recorded as dead, the disappeared remain on official registers as still alive, for reasons of political expediency: Halwani notes that to acknowledge their deaths would be compromising to both the Lebanese and the Syrian governments. Never granted the closure of individual death or burial, these people have instead been left in the abstract limbo of collective “martyrdom.” They are the “immortals,” as Halwani calls them. Two representatives of this vast shadow population are finally seen walking down a Beirut street in one of his minimalistic drawn films, transparent ghosts in black outlines against white. It’s the final moment of Halwani’s sensitive but provocative act of symbolic exhumation—or, you might say, re-animation.

Jonathan Romney is a contributing editor to Film Comment and writes its Film of the Week column. He is a member of the London Film Critics Circle.