Film Comment Recommends: The Kalampag Tracking Agency

This article appeared in the August 18, 2022 edition of The Film Comment Letter, our free weekly newsletter featuring original film criticism and writing. Sign up for the Letter here.

Discussions about film history in the Philippines usually resemble elegies. Due to government neglect and a lack of funding for preservation, thousands of Filipino films have been lost over the years, creating what film scholar Bliss Cua Lim has called an “archival crisis” that places the country’s moving-image heritage at risk. The Kalampag Tracking Agency, a program of experimental shorts curated by Shireen Seno and Merv Espina, moves past the tendency to merely lament the loss of these works. Screened in various states of restoration and degradation, and covering the period from the end of Ferdinand Marcos’s dictatorship to the present day, the shorts in Kalampag assemble an alternative film history that accommodates the imperfection and incompleteness of the archive.

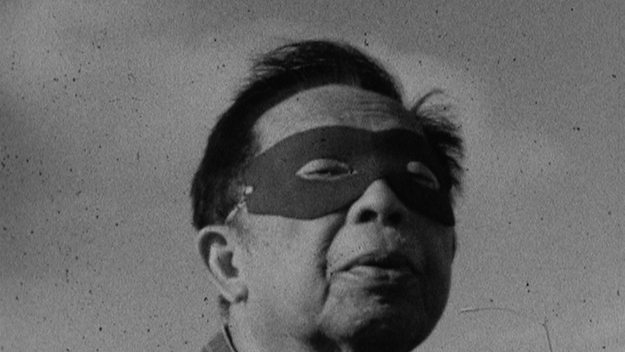

In their program notes, Seno and Espina explain that “kalampag” in Tagalog refers to a mechanical bang—a sound signaling that something has jammed, come loose, or fallen off. A shock to the system, or maybe a glitch. Their use of this term is similar to Hito Steyerl’s concept of the oft-discarded—but noble—“poor image,” though Seno and Espina apply it to both digital and physical media. Some films in Kalampag are literally made of refuse: Tito & Tita’s Class Picture (2012) uses expired short ends of 16mm film to replicate the look of faded yearbook photos, containing fuzzy, unrecognizable faces. R.J. Leyran’s mesmerizing montage of action scenes, Riddle: Shout of Man (1990), was made from decaying found footage dumped in a creek outside a film studio. Other films approach loss and degradation in a more metaphorical sense: Miko Revereza’s Droga! (2014) ponders the filmmaker’s fraught experiences of identity as an undocumented Filipino immigrant in the U.S., and Martha Atienza’s Anito (2012) portrays a parade during the Ati-Atihan festival on Bantayan Island, where traditional fishing livelihoods are imperiled by climate change.

Many of the films have been converted multiple times across formats (whether for artistic or distribution purposes) and severed from the contexts in which they were originally developed. A paradigmatic example is Raya Martin’s Ars Colonia (2011), commissioned by the International Film Festival Rotterdam: it was shot on Hi8 tape, transferred to 35mm film stock and hand-colored, then projected on film or HD video as a header before films financed by the festival’s Hubert Bals Fund. Tad Ermitaño’s The Retrochronological Transfer of Information (1994) contains hardcoded Japanese subtitles, because it was sourced from a VHS at a now-defunct Japanese television station. These idiosyncrasies invite us to study the technical specifications and credits of these films, which contain clues about how they were bankrolled and circulated. In this way, Seno and Espina mobilize the film screening as a kind of crowdsourced archival practice: by touring the program in the Philippines and abroad, they have collected important information about the films from audience members and used the resources of each arts institution to create better transfers.

My favorite selection in Kalampag is Cesar Hernando, Eli Guieb III, and Jimbo Albano’s Rust (1989). One of several films in the program that were produced at workshops sponsored by Mowelfund and the Goethe-Institut of Manila in the ’80s (and led by German experimental filmmaker Christoph Janetzko), Rust cuts between a scene from Peque Gallaga’s controversial erotic thriller Scorpio Nights (1985) and footage of U.S. military incursions and anti-American protests. A man descends on a woman under the shimmery veil of a mosquito curtain; as they fuck, soldiers roll into fields and cities on Jeeps, leaving imperialist destruction in their wake. The film’s hazy, sepia-tinted images erupt like a roiling cauldron of sex and brimstone, superimposing colonial violence and carnal desire. They bring to mind one of the many tragedies of the American colonial period in the Philippines: only five of the estimated 350 Filipino films produced during this time (1898-1946) are known to have survived. Like all of the films in Kalampag, Rust embodies the tension between remembering and forgetting, life and death.

Emerson Goo is a writer from Honolulu, Hawaiʻi. He is currently pursuing an undergraduate degree in landscape architecture at Cal Poly, San Luis Obispo.