Film as Art: Daydreaming with Stanley Kubrick

This past summer, an extensive exhibition entitled Daydreaming with Stanley Kubrick has occupied the West Wing of London’s Somerset House. It was co-curated by artist and musician James Lavelle, a founding member of the English trip hop band UNKLE and the Mo’ Wax record label, and curator James Putnam of University of the Arts, London. Over 50 artists in contemporary art, music, film, fashion, performance, photography, and sculpture contributed either new or existing works that owe their inspiration (or a sort of fellow feeling) to Kubrick. “Daydreaming” has a very catchall ring when applied to the experience of any body of films, although in the case of this variegated sampling of Kubrick’s oeuvre, daydreaming breaks down into many states of consciousness.

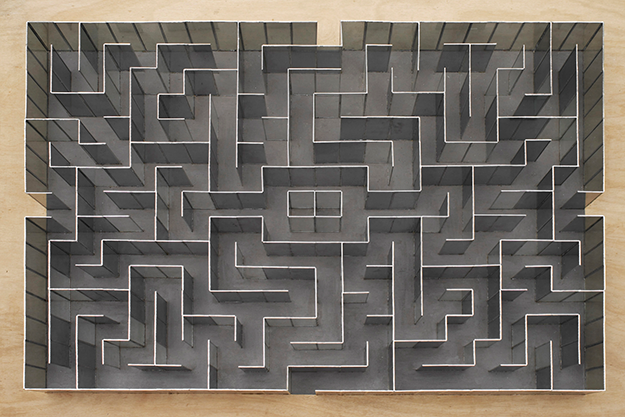

The exhibition aims, for one thing, to extend our sense of “Stanley Kubrick” by fragmenting and reassembling the elements of his films in different ways. The 45 exhibits, or installations, in this ambitiously curated show each take off from a Kubrick film, or a situation, motif, or atmosphere within the films, and spin this out into a self-contained version of “Kubrick.” Running through the hallway is exhibit no. 9, The Shining Carpet, a floor covering patterned after the hallways in the Overlook Hotel.

The Shining also figures, for example, in Stuart Haygarth’s PYRE, a pyramid of glowing electric fires which references a scene, according to the Somerset catalogue, “Kubrick shot twice, once for Jack Nicholson’s take, and once to capture the roaring fireplace.” In Stephen King’s original novel, fire engulfs the Overlook, and it’s a visual motif in the film (or is that just the hell Nicholson’s character makes of the Overlook?). But it’s an element that anchors this installation too explicitly. To the extent, in fact, that the installations isolate elements of plot or theme (or motifs, a major example being the eye) there seems little room left for daydreaming. Something similar undermines No. 7 (In Consolus – Full of Hope and Full of Fear), James Lavelle and John Isaacs’ rumpus room for giant-sized teddy bears, dressed in Clockwork Orange or Lolita outfits, amidst a litter of enlarged cereal boxes like an explosion of the Shining pantry.

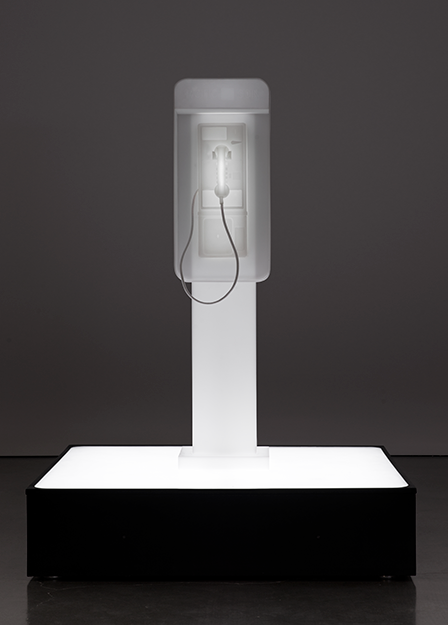

Nothing could be more apparently self-evident than a public payphone, lit in a soft glowing white light in a large four-sided room of mirrors (as in Doug Aitken’s 2014 installation Twilight, now a featured display in Daydreaming). But if “communication” is the theme here it seems as all-encompassing and finally non-communicative as anything in 2001. Where a thematic or narrative clincher is missing, the installations occupy their own mysterious space that can be both baleful and teasingly elusive (Kubrickian in their own way). The show’s second piece, by Mat Collishaw, does a little reverse take on 2001’s evolution. A space helmet sits inside a glass case, and a film projected within the helmet shows a chimpanzee in a rocky landscape investigating the camera (poking it with a stick: he’s grasped the principle of tools) while a skull—all our yesterdays and tomorrows?—floats in the background.

In some cases, the element of mystery that detaches an installation from Kubrick is the artist’s personal connection with the film that he or she is referencing. The “semi-autobiographical” Anywhere Out of This World, written by actress Samantha Morton and directed by Douglas Hart of the Jesus and Mary Chain, shows a little girl taking her solitary seat in a cinema showing 2001, though the climactic stargate/transformation is now set within more violently transgressive scenes of childhood nightmare and sexual assault. Composer Michael Nyman has spoken of his terror on first seeing Dr. Strangelove, and his A Phoney War is a hypnotically distorted montage of frantic telephoning in the film, linked with stock footage shots of operators busily working the lines (or is this the Omsk information switchboard which the Russian premier tells the U.S. president to call at one crucial moment?).

In a show that is a hymn to the art and artistry of Kubrick, what is often most piquant are exhibits that dwell on matters of craft, the way his “vision” involved the painstaking and time-consuming assembly of physical materials. In No. 15’s collection of glass objects, for domestic or scientific use, each is engraved with the title of a Kubrick film, like a set of crystalline Kubrick props (or “a swim in the Kubrick aquarium,” as artist Seamus Farrell describes his work here).

Then there is the overwhelming Kubrick factory assembled by Iain Forsyth and Jane Pollard in Requiem for 114 Radios. A cavernous room is filled with littered electrical worktops and research tools such as The Amateur Radio Handbook and The History of Napoleon Bonaparte, while the voices of individual singers performing a version of the “Dies Irae” are broadcast over 114 analog radio sets (the inspiration being Dr. Strangelove’s CRM114 Discriminator).

Requiem’s soundscape infiltrates many of the other soundtracks in the exhibition, and it’s hard to escape the impression that Kubrick himself might have designed the elegant, flowing spaces of the neoclassical Somerset House (from his favorite period, the 18th century). For a disconcerting moment, the Andrews air conditioner humming in a corridor might be taken for another artifact, but it seems to be the real thing.

The 45th and final installation, by Joseph Kosuth, winds up and around one of the building’s architectural showpieces, the Nelson staircase, its pale gray-greenish walls backing a staircase in white marble and blue-painted iron. Following you up along the walls is transcribed dialogue from a scene in The Shining, as Shelley Duvall backs up another staircase, tearfully fending Jack Nicholson off with a baseball bat as he reassures her that he wants to do nothing more than bash her brains in. Reading the dialogue as you drift up around the staircase is itself a kind of daydreaming, the kind of dislocated state Kubrick often achieved by setting off extreme violence with mockingly elaborate art direction (perhaps taking his cue again from 18th-century rococo).

Richard Combs is a longtime contributor to FILM COMMENT.