Festivals: Vienna

Noroît

“Tonight, I am double”: this cryptic declaration, delivered by Bernadette Lafont’s pirate queen moments before a nocturnal duel to the death with her vengeful doppelganger (Geraldine Chaplin) at the climax of Jacques Rivette’s psychedelic and balletic Noroît (1976), curiously resonated with a number of the films included among the selection at this year’s Viennale. In Noroît, these words serve to acknowledge that its two female leads are each other’s double, counterparts whose eternal feud mirrors that of the goddesses played by Juliet Berto and Bulle Ogier in Duelle, the film which preceded Noroît in Rivette’s never-completed “Les Filles du feu” series. But the notion of “being double” also conjures a sense of multiplication and division, of expansion and contraction, of films surprising us with decisive changes to their own shape and scope. Indeed, several of the 2016 Viennale’s standout titles dynamically pulled the rug out from under you.

Noroît, which was presented in a new digital restoration, is one of the most delirious works by the late French master of going-long. We meet our protagonist Morag (Chaplin) having a meltdown on a beach over the demise of her brother (film producer Humbert Balsan, who also acted in Bresson’s Lancelot du lac and assistant-directed on The Devil, Probably). She infiltrates the ranks of the pirates responsible for his death (including one played by Balsan in a double role) and slowly but surely enacts her revenge plot against their groovy, swarthy boss Giulia (Lafont) with the uncanny precision of one who is fully aware that she exists within a fiction. (Adapted from Cyril Tourneur’s The Revenger’s Trilogy, Noroît marks the only time that Rivette adapted a play.) In counterpoint to the sense of predetermination effected by Morag’s patient angling for her shot at the head honcho, Rivette increasingly litters the mise en scène with anachronistic objects and costumes and with lanky figures pirouetting, lunging, swinging swords and firing rifles as if in some kind of acid jazz remake of Minnelli’s The Pirate. Rivette untidily concludes the film with an eruption of the supernatural that reveals to us just how far we’ve drifted away from reality and toward a disarmingly nightmarish, artificial space, well past the point of safe return. Noroît is perhaps Rivette’s most frightening film, but also the one in which the choreography of bodies within the frame does the most to conjure a film-drunk world where the lightness of fiction clashes with the weight of real madness.

Anocha Suwichakornpong’s By the Time It Gets Dark (Dao Khanong) is a wholly different kind of head movie, though the freak-out it builds up to is similarly methodical in its presentation. By the Time It Gets Dark initially concerns itself with a young director’s friendly rapport with an older woman whom she is interviewing for a film on political activism among students in 1970s Thailand, their time together simmering with intellectualism and a hint of ethereality. Then, at around the film’s halfway point, the seams begin to fray before completely unraveling as we move, always surprisingly, from one new narrative to another: first, there’s a kind of Cliff Notes version of the film so far, albeit with different characters and a pronouncedly distinct tone; then, we follow an actor caught between performing and being, though his existence is ultimately revealed to be not at all what it seems; then, yet another film director, coping with sudden and tragic news; and finally, a waitress whose presence triggers a stylistic crescendo, a boiling-over in which the film’s visual imagination overwhelms its fidelity to narrative per se. By the Time It Gets Dark is a swirl of startling, sensuously rendered transitions, identities sliding among characters, fictions cracking open to reveal still more fictions within. This film marks only Suwichakornpong’s second feature, but it already suggests a heady iconoclast snooping out profound points of exchange between the possibilities of narration through images and the politics of memory.

By the Time It Gets Dark

The relation between images, politics and morality is explored with similar aplomb by Abel Ferrara in King of New York (1990). Beyond good and evil indeed: Ferrara’s film doesn’t necessarily ask us to identify with its irredeemable crooks, but it does make painfully clear how, when God is dead and the almighty dollar rules, the supposed “good guys” are often just as bad as their villainous counterparts. King of New York screened in the context of a tribute to Christopher Walken, and his performance here as fresh-out-the-joint hipster kingpin Frank White lives and dies on Walken’s unparalleled capacity to play low-key menacing and enticingly lively. His sauntering—across the floor of a crowded, expensive restaurant; right past the hood standing guard outside a mafia-run card game; from the living room of his room in the Plaza Hotel to the balcony where he can survey his kingdom-to-come—radiate an infectious, weirdo gracefulness, and Laurence Fishburne chips in a career-best turn as White’s most trusted trigger-man, a swaggering volcano of lewd disses, glimmering gold caps, and remorseless killings.

To see King of New York on celluloid unlocks its startling alternations between warm, honey-gold interior scenes suffused with lavish, late-’80s Manhattan decadence and ice-cold, dark and dank exterior scenes with a vacuum-like atmosphere (the unnerving backdrop for the film’s climactic chase/shootout, with amoral cops David Caruso and Wesley Snipes trying to cover their own asses by rubbing out Walken and Fishburne). A dialectical masterpiece that’s even better and less silly than I remembered, King of New York is anchored by a complex moralism with a dash of fatalistic cynicism that cuts awfully deep in a year of police shootings, dashed political dreams and, of course, more of the same ol’-same ol’.

The Challenge, the first feature by the Italian filmmaker and video artist Yuri Ancarani, addresses our present through the prism of a group portrait of wealthy sheikhs in Qatar with a passion for falconry. With formal rigor and a leisurely sense of pacing, Ancarani leads us through the rituals that comprise their lifestyle—when not on their phones, the men spend their time perilously racing their SUVs up and down the dunes, calling into televised auctions to bid on primo birds, chowing down communally, and lounging with someone’s leashed-up pet cheetah. Ancarani’s film doesn’t so much revel in the sheikh’s comical excesses as it carefully trains its focus on these men for whom money is basically no object, at work (well, if training their falcons counts) and at rest, with hobbies and chores dissolving into a single stream of exactingly chronicled play. Perhaps what’s most striking about The Challenge is how it forwards an image of men committed to being together and individually pursuing their idiosyncratic, gaudy desires, regardless of the price tag—Hawksian, almost!

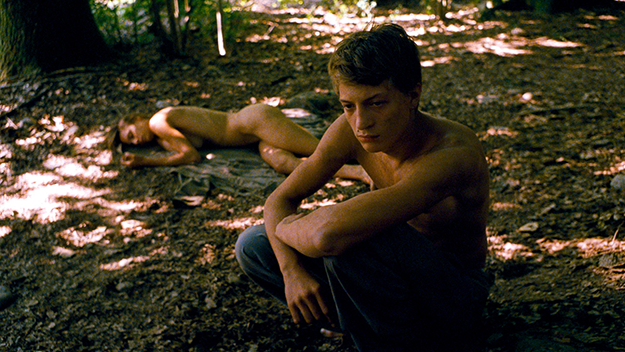

Happy Times Will Come Soon

Another shapeshifter, and one of the year’s most beautiful and beguiling films, is Alessandro Comodin’s Happy Times Will Come Soon. We begin with a handheld camera shadowing two young goofballs of an unspecified historical period as they break out of prison and wander through the northern Italian woods with a dog, roughhousing, foraging for mushrooms, finding and incautiously playing with a rifle. One violent twist later and we now appear to be in the present, as locals at a bar recount a regionally well-known folktale concerning a wolf’s tragic passion for an angelic white doe. Then, we more seamlessly transition to the tale of Ariane, a villager going about her daily routine despite word of hungry wolves on the prowl. What follows is a dark (and naturally lit) descent into the heart of the heart of the woods, with enigmatic liaisons and phantasmagorical events unfurling with the tactility of unadorned reality.

The individual sections of Happy Times Will Come Soon operate under fascinatingly distinctive logics: first, a drifting, free, almost non-narrative mode that privileges play, physicality and homoeroticism; then, a more recognizably documentary mode fueled by discourse, testimony and mythology; finally, an oneiric mode in which desire itself—both conscious and unconscious—serves as our sole flashlight amid the trees, the shadows, the mud-smeared bodies, the ominous ambience and the lingering threat of violence.

Comodin ties it all up (though none too neatly) with a prison-set coda that self-consciously tips the film’s hat to Bresson’s Pickpocket. The homage is spot-on: like Bresson, Happy Times Will Come Soon evidences Comodin’s feeling for moods and ideas that defy verbal expression with a restraint that speaks as much to the means at his disposal as to his aversion to embellishment and the seriousness with which he regards the film’s subjects. Which isn’t to say that Happy Times Will Come Soon is humorless or too tightly-wound—far from it, the film is as open and airy as any I have seen this year, a mysterious object whose form and meaning plainly shift the longer it remains within our field of vision, like an obscure figure glimpsed at a distance in the night.

The Deer Hunter

The late Michael Cimino’s The Deer Hunter (1978) is another work whose qualities change dramatically depending on the spectator’s position relative to it. Often described as fascist for its crude depiction of the Northern Vietnamese as sadistic, psychotic and animal-like, it’s also been exalted for its richly sketched portrayal of a small Pennsylvanian factory town and the people who inhabit it. Indeed, few major American films of the 1970s have so contentious a legacy, which should probably put us on notice that The Deer Hunter merits a closer look today, especially with its beleaguered helmer’s death this past July.

The story has a timeless quality yet is unmistakably rooted in its time: a trio of Russo-American steel workers (Robert De Niro, John Savage and Walken) in Clairton, PA spend time with friends as their enlistment in the military and subsequent deployment to fight in Vietnam draw closer by the day. Savage’s Steven marries his girlfriend Angela; their debaucherous wedding, presented in Renoir-esque longhand, serves as the men’s send-off from the town (not to mention a final chance for De Niro’s Mike to holler at Walken’s sweet, innocent girlfriend, utterly lived-in by Meryl Streep in just her second feature film). The gang undertakes one last hunting trip with their cronies (including John Cazale, whose Stan is a cocktail of self-loathing misogyny and castration anxiety), and then, one notoriously abrupt cut later, we’re in the Paradise Lost of Vietnam at the war’s height as Mike takes a flamethrower to a family-murdering Vietcong grunt.

The physical and spiritual violence of the second act of The Deer Hunter is about as heavy as it gets, but what’s more striking is how Cimino moves from Clairton to Vietnam and, in the third act, back to Clairton and finally to Vietnam once more: in their simplicity and disorienting suddenness, these hard, sharp transitions are affecting and economical in a way that seems fascinatingly at odds with The Deer Hunter’s narrative and emotional maximalism. With the simplest of cinematic devices, Cimino tears away the placidity of proletarian Anywheresville and brusquely resituates us in a numbing world outside common-sense morality, a kill-or-be-killed land with a certain resemblance to Ferrara’s New York. And the return trip is, of course, in no way pacifying; we’ve already been through and seen too much to simply re-acclimate, and it’s not long before Mike gets back on the plane to settle some business in the only way that Cimino’s film can possibly allow.

King of New York

The Deer Hunter was included alongside King of New York in the festival’s Walken mini-retro, and his turn as Nick is a captivating sideshow next to De Niro’s straight-man at the film’s center. By the time that Nick has lost his mind and his woman, entrenching himself in Saigon (rendered as Macao meets the innermost circle of hell) as a pathologically fearless Russian Roulette champion, the stage is set for a re-entrance for the ages: he walks into the crowded room of depraved gamblers in which his reunion with Mike awaits, striking an almost triumphant pose with eyes that now only seem capable of seeing the truth of things behind their appearance. This momentary flourish, wherein mise en scène and performance align effortlessly, says infinitely more than does Cimino’s bravado, grotesque scenes that strain to illustrate war’s boundless horror or the on-the-nose rendition of “God Bless America” with which the film infamously concludes. A perfect yet not at all showy gesture that alludes to so much more than could ever fit within the film frame, utterly shattering and well-worth the wait.

Dan Sullivan is the assistant programmer at the Film Society of Lincoln Center.