Festivals: To Save and Project 2016

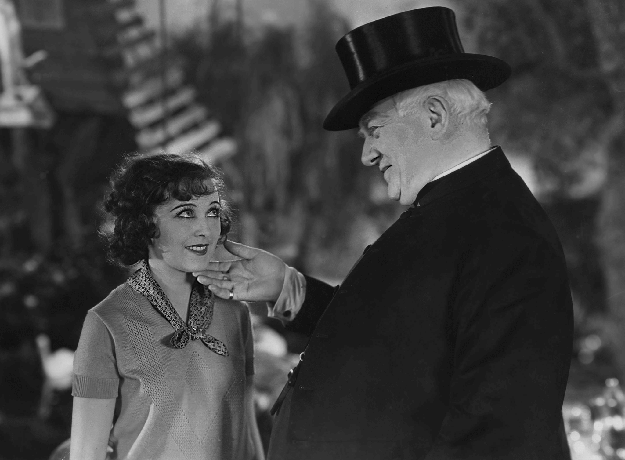

The Brat

This year, the 14th for the Museum of Modern Art’s film preservation series To Save and Project, brings some rarities back to New York audiences. Particularly exciting to me, as a proud example of what film writer Will McKinley likes to call an Old Movie Weirdo, is a trio of early 1930s films that have little in common except freshly restored beauty and a bizarre line in sexual innuendo.

Screening early in the series is The Brat, an atypical John Ford film from 1931 that hasn’t been widely available for years. MoMA itself has restored the film in the nick of time from one iffy nitrate print, and it’s little the worse for wear. The finest scenes are in the opening, outside a fog-bound night court as police officers (including Ward Bond, so young it took me a second to be sure it was him) unload the paddy wagons, and then inside where the prisoners hear from the judge. The lighting, via the great cinematographer Joseph H. August, recalls the German Expressionist stylings the two men created for The Informer four years later. But the somber look is deceptive, as the scenes skate not only from high to low angles, but also from sentimental to near-slapstick. This seems to be the milieu that interested Ford the most; one character, a broken-down alcoholic actress played by Louise Mackintosh, gets a chance to declaim part of Portia’s speech from The Merchant of Venice while posing so she appears to be bathed in footlights. It’s such a perfect bit that you expect her to appear again, but she doesn’t.

No, the story is about a young woman, the brat of the title played by Sally O’Neil, who’s been picked up for ditching the check for a spaghetti dinner. She’s taken under the wing of a pampered society novelist (Alan Dinehart) who is in court to do research. He whisks the Brat off to his Long Island estate, where she runs afoul of his doting mother (Mary Forbes) and the two neighboring sisters, fair (Virginia Cherrill) and dark (June Collyer), who hope to win the novelist’s rather limp hand. Like every spunky orphan from Pollyanna to Annie, the Brat upends the rich household, and nothing very surprising occurs. What’s surprising is how consistently delightful the movie is throughout, aided by lighthearted dialogue one suspects had much to do with co-writer S. N. Behrman. It is based on a play, but seldom looks stagy. You sense Ford amusing himself with a shot that follows the Brat’s showgirl-style leg lifts on a rope swing, and with a catfight between O’Neil and Cherrill. The hair-pulling, dress-ripping, and back-and-forth straddling is obviously unchoreographed, and Ford claimed it was also un-acted, as the two actresses loathed one another.

Deluge

Also on the menu at MoMA is the restoration of Deluge, a spectacular RKO disaster flick from 1933, directed by Felix E. Feist and at one point believed to be lost. Deluge has been missing in action for decades, available only in a dubbed Italian version that was literally retrieved from a basement. In a happy ending quite at odds with Deluge itself, a 35mm nitrate negative with the original English soundtrack was discovered, and has been used for the 2K restoration by Lobster Films in Paris, which MoMA is presenting in its North American premiere. Kino Lorber plans a theatrical release and special edition Blu-ray/DVD in coming months.

The movie is more front-loaded than a lot of later disaster films. There are only a couple of pre-calamity scenes to introduce any characters, and most of the people you see early are in the process of being wiped off the map. There is not a lot of explanation as to just what in blue blazes is going on. Nope, what you are told is that the barometer is plummeting, worried weather forecasters are calling in all the ships at sea, and then, wham, the West Coast has crumbled into the ocean and a tsunami is crushing New York. (Yes, even in the 1930s, filmmakers just loved to destroy New York.)

It’s fantastic miniature work—the disaster looks almost as good as the earthquake in San Francisco, better even than later entries such as the dam bursting in The Rains Came and the earthquake in Green Dolphin Street. Once it’s over, Deluge becomes a postapocalyptic tale, as Sidney Blackmer works to find his lost family, only to encounter lovely distance swimmer Peggy Shannon, who is fleeing the unkempt attentions of Fred Kohler and his pals. Eventually Shannon and Blackmer are being hunted by Kohler and his posse and the plot of Deluge begins to resemble a zombie movie. The pursuers aren’t flesh-eating, but that’s probably only because it hasn’t occurred to them yet. Nevertheless very little about this movie plays to the expected disaster-flick clichés, especially the ending, which mixes survival with despair.

Cock of the Air

Finally we come to Cock of the Air, the lubriciously titled Howard Hughes production from 1932 that has been restored jointly by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences and the Film Foundation. Every part of this movie appears to be a calculated affront to the Hays Office, which had its revenge, cutting nearly 12 minutes out of the film. Even in the so-called pre-Code era, the censors could show their teeth. The film has been reassembled in near-complete fashion, but part of the soundtrack is still missing; talented actors were hired to double the stars’ voices—including Hamish Linklater subbing for Chester Morris and Marin Hinkle for Billie Dove. A little scissor-and-film icon appears in the lower right corner when a censored moment pops onscreen.

Morris, later the star of the Boston Blackie series, plays the title role, a World War I flying ace famed for his sexual conquests. Dove, who plays an equally amorous French actress and improbable star of a Joan of Arc play, was Hughes’s lover at the time. (He proposed marriage, but Dove wound up walking away.) True to Hughes’s enduring fascination with the female décolletage, Dove’s costumes are cut so low that simply reaching up to change a lightbulb could result in disaster.

It is a bizarrely conceived movie, one that recreates the then-greatest bloodbath in modern history as fizzy fun, with nary a German enemy in sight. The script was written by Robert E. Sherwood and by Charles Lederer, whose talent is much in evidence in his adaptation of The Front Page, a meticulously restored version of which is also playing the festival. But the plot and the dialogue play out as an overextended smutty joke, the peak of the film’s wit being Dove in her Joan of Arc armor facing a can-opener-wielding Morris.

Cock of the Air

The main reason to watch Cock of the Air isn’t the innuendo, which doesn’t approach something like Baby Face or Red Headed Woman, nor even the wide-open spaces between Dove’s chin and the end of her breastbone. No, the best reason to see Cock of the Air—and I recommend it highly—is the direction by Tom Buckingham. The movie is one long, delicious moving shot after another. One slow swoop down a banquet table, and then back again, reminded me of a similar shot in Max Ophuls’s La Signora di Tutti. Buckingham soon follows that with a fabulous track down a Carnival-crazed Italian street. Even a relatively simple scene of Dove walking to meet Morris in an ornamental garden provides an excuse for the camera to glide beside her all the way.

Once you’ve read the title you’ve sampled the movie’s biggest double-entendre, but Cock of the Air’s worth is in its gorgeousness. There is not a lot of information immediately available on Tom Buckingham, other than that he died young. Hopefully To Save and Project will revive interest in him, as it has many others.

Farran Smith Nehme writes about classic film on her blog, Self-Styled Siren, and recently published her first novel, Missing Reels. She is a member of the New York Film Critics Circle.