Festivals: Busan

The Master

Celebrating its 20th year, the Busan International Film Festival should scream stability. One of Asia’s biggest film festivals, screening approximately 300 movies from 70 countries, host to the 10-year-old Asian Film Market (1,500 badge-holders and counting), and housed in the brand-new $150 million Busan Cinema Center, the event looks like a temple of permanence from the outside. But inside, the BIFF is a festival in crisis, both logistically and artistically.

In retaliation for the festival’s 2014 screening of muckraking agit-doc The Truth Shall Not Sink with Sewol, which shone a spotlight on the Korean government’s bungling of the Sewol ferry disaster, the mayor of Busan campaigned (unsuccessfully) for the removal of the BIFF chairman. More successful was a surprise audit of the festival’s finances in late 2014, after which KOFIC (Korean Film Council, part of the Korean government’s Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism) slashed Busan’s budget by 45 percent as an act of revenge (while increasing the budgets of two smaller film festivals). The festival weathered that financial gutting thanks to private sector support, but its Asian Film Market had far fewer attendees this year, and with no industry heat it’s starting to stink of gangrene and may be the first limb to get hacked off.

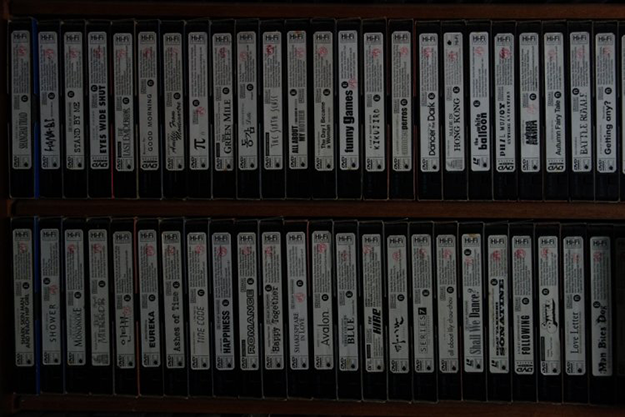

But the bigger problem with the festival wasn’t actually the festival’s fault. Exposed center stage, somewhat unwittingly, by the Thai documentary The Master, it became clear that an artistic rot is creeping across Asian film. Directed by Nawapol Thamrongrattanarit (Mary Is Happy, Mary Is Happy), The Master is a series of talking heads discussing Mr. Van, a mysterious bootlegger whose Bangkok stall offered Thai film-nuts hundreds of pirated art films from the 1990s through the 2000s that lacked distribution in their country. Mr. Van’s piracy pipeline fed the addictions of critics, theater owners, teachers, films fans, and filmmakers (Pen-ek Ratanaruang and Shutter’s Bangjong Pisanthanakun among them) and it reminds Busan audiences that the 1990s and early 2000s witnessed a geyser of Asian talent as directors like Hirokazu Kore-eda, Tsai Ming-liang, Zhang Yimou, Takeshi Kitano, Kiyoshi Kurosawa, and Wong Kar Wai all exploded onto the international scene. Seeing their posters in Mr. Van’s shop makes this year’s BIFF with its 300-plus films feel haunted by the ghosts of past directors. More than ever before, the Asian film scene is like a deserted mansion of shadowy whispers, dusty rooms, and a few ghouls in the basement feeding off the corpses of older, better films.

Chaotic Love Poems

Revered old masters like Hou Hsiao-hsien and Kore-eda premiered their new movies at other festivals, and their inclusion in BIFF feels like due diligence rather than discovery. The newer wave of acclaimed directors offered up one disappointment piled on top of another. Li Yu, for example, is one of the best female directors working in China, and her rock-solid relationship with mega-diva, Fan Bingbing, affords her reliable access to funds for movies like her surrogate-mama drama Lost in Beijing (07) and her compelling coming-of-age movie Buddha Mountain (10). With Mainland Chinese audiences showering money on contemporary romances and comedies it makes sense that Li Yu is cashing in with Ever Since We Love, about students drinking, dissecting, fighting, and fucking their way through med school. Though refreshingly frank about sex, and featuring more empowered female characters and visual imagination than any other five Chinese films this year, the movie is ultimately declawed by adherence to its genre. From frame one, you know these characters are going to learn about life and love with wry bemusement, and every heartbreak will be redeemed by a happy ending.

Also selling out to commercial forces is Garin Nugroho whose Opera Jawa (06) stunned festival audiences by rooting its contemporary romance in the Ramayana and transforming it into a classical Javanese performance full of gamelans, installation art, and dynamic visuals lifted from Legong and Kecak. With Chaotic Love Poems, he’s traded that conceptual audacity for banal mediocrity, stretching out a Romeo-and-Juliet story over three decades of middlebrow clichés and poop jokes. Royston Tan promises audacity in 3688, a Singaporean musical about parking meter maids powered by Fong Fei-fei Mandopop tunes from the Seventies and Eighties. In a clever bit of narrative punning, Tan has taken the nickname for Singapore’s meter maids, called “Fong Fei-fei” because of their sun hats, and used it to justify the Fong Fei-fei tunes in this nostalgia-fest. But by the time he’s also crammed in a dad with Alzheimer’s, an American Idol-esque singing competition, a rivalry with a transgendered diva, workplace warfare, a Love Story love triangle complete with leukemia, a parking-diva-versus-automatic-parking-meter struggle, and bouts of random hip-hop-rhyming, his film ends up feeling like the work of a hyperactive 3-year-old on meth.

By contrast, Sion Sono’s The Virgin Psychics has a laser-like focus on its themes—which are wanking and boobs. Sono has five other features out this year so it feels grumpy to pick on any one in particular because another will be along in a minute, but Virgin Psychics is boring, which is not what you want from a softcore jumble about psychics, nude teleporters, and cleavage. As innocent as a Bloomingdale’s underwear catalogue, it feels like something Sono tossed off in the bathroom stall while taking a coffee break. I don’t particularly object to screenings of Sono’s soiled celluloid tissues, but even the biggest fan would have to admit that it’s a far cry from his magisterial Love Exposure (08) or even his great sex film, Guilty of Romance (11).

A Copy of My Mind

One of the few name-brand Asian directors to successfully navigate the border between art-house filmmaking and commercial cinema at Busan this year was Joko Anwar, Indonesia’s visually flamboyant purveyor of genre thrills (Janji Joni, 05; Kala, 07; Forbidden Door, 09) who births his second political thriller with A Copy of My Mind. Ditching his usual slick production values for a handheld, shot-on-the-fly aesthetic, Anwar hooks eyeballs with the dynamic chemistry between his leads, Tara Basro, a salon slave who wears herself out giving facials to pampered housewives, and Chicco Jerikho, a shaggy-haired slum-dweller with rock-hard abs who makes his living subtitling pirate DVDs by cutting and pasting their dialogue into Google Translate. Shot in 10 days for $10,000, and produced by Korean mega-studio CJ Entertainment, it’s 75 percent verite love story and 25 percent ballot-box noir. A hair too elliptical for its own good, A Copy of My Mind still felt like Three Days of the Condor compared to other films at BIFF, even though it’s really just a beautifully acted love story with some paranoia politics on the side.

Already limping along for a while, Korea’s one-time bad boy of cinema Kim Ki-duk demonstrates total aesthetic exhaustion with Stop. Filmed in the still-radioactive forbidden zone around Fukushima, and shot with a Japanese crew and actors, the result is as unloved and unwanted as the pregnancy at the heart of his abortion drama. In a telling sign, Kim’s next movie is a $30 million Korean-Chinese co-production called War Is God, because China is where Korean filmmakers go when they die. Mainland mega-hit director Feng Xiaogang has teamed up with Korean director Kang Je-Gyu (who hasn’t had a hit since 2004) to produce the tepid BIFF entry, Bad Guys Always Die, the directorial debut of Feng’s longtime AD, Sun Hao. A weak attempt to make a manic Coen Brothers clone about vacationing Chinese tourists running afoul of evil kidnappers on Korea’s scenic Jeju Island, nothing on-screen even remotely resembles actual human behavior. A painful collection of shopworn setpieces, recycled jokes, and stock comic characters, the “ain’t I wacky?” grin plastered across the film’s big dumb face makes you feel like you’re being tortured to death by a clown.

But with Korean and Chinese audiences delivering big bucks for blockbuster hits, you can understand why young directors are copying crass commercial hits wholesale in hopes of winning the boffo box-office lottery. What’s less forgivable are the young directors copying festival award winners as they try to titillate French sales agents and prestigious international film festival programmers into championing their fake philosophical enquiries into human existence. Leopard Do Not Bite from Sri Lanka may feature BIFF’s only close-up of a giant Sri Lankan boner being nibbled by fish, but by the midway mark half the audience around me was dozing, and five minutes later I joined them. It was a demolition derby of thrills, however, compared to Korean art film Eyelids, which opens with a five-minute shot of waves lapping against the shore, or Sri Lanka’s Dark in the White Light, which promises serial killers, rapist doctors, and organ harvesters but doesn’t take long to reveal itself as just another collection of empty artsploitation gestures mostly borrowed from Michael Haneke.

Girl on the Edge

Generally, the Korean line-up was the most consistently disappointing at BIFF. The selection boasted not one but two horror(-ish) movies about tubercular children (The Silenced and The Piper), and while both looked good on paper (a Suspiria-inflected boarding school ghost story and a rat-horror retelling of The Pied Piper of Hamelin, respectively), neither offered any compelling justification for their existence. Korean comedy-dramas like Ordinary People and One Way Trip were supposed to be madcap, anti-authoritarian romps, but it’s hard to deliver anarchy when your stories are bogged down with sick mamas, devoted grandmas, and slapstick fat cops.

Amidst all this dumb fumbling, it was a welcome surprise that the most satisfying moviegoing experiences came from the least commercial segments of the Korean film industry. Like the burst of talent that came out of American film schools in the Sixties and Seventies, graduates of Korea’s KAFA (Korean Academy of Film Arts) proved the most adept at bringing a tough-minded artistic sensibility to genre filmmaking, demonstrating that they were capable of connecting with an actual audience. KAFA produces three feature films a year, written and directed by its students, and budgeted at about $169,000 each. They’re often artsy to the point of perversity, but hit a historic high with last year’s Socialphobia (14), a taut thriller about social media, bullying, and suicide that became a modest box office hit, and this year’s Alice in Earnestland, a widely praised black comedy starring veteran actress Lee Jung-Hyun (A Petal, 96; Roaring Currents, 14) which was also a box-office success.

Kong Ye-Ji’s performance as the titular Girl on the Edge is all narrow-eyed suspicion and snarling, sneering menace, and it’s what carries the movie across the finish line even as it runs out of conviction halfway. Kong plays a teen street punk who teams up with a good-girl classmate to locate her missing mother, and after starting as a street-life drama, the movie turns into a Dickensian gothic melodrama about missing mommies, dying daddies, lost wills, lunatic asylums, and gold-digging home health care attendants. But Kong’s adrenalized performance and the film’s first 45 minutes of kitchen-sink realism are a beacon of hope in the festival’s vast wasteland.

The Boys Who Cried Wolf

Far more successful is another KAFA project, The Boys Who Cried Wolf, a neo-noir as accomplished as Night Moves or Cutter’s Way, shot on crowded Seoul streets in gray, smog-clogged light. Park Jong-Hwan plays a struggling actor who makes his rent as a body for hire, pretending to be a boyfriend, or a friend for people who have neither. When a woman asks him to pretend he witnessed a crime, he’s willing to take the money (because of a sick mother—one of the terse screenplay’s few contrivances), but then things get complicated, as they tend to do in noir. Park’s previous roles as “Attendee at Information Meeting” and “Employee on Roof” don’t hint at the relentlessly interior performance he delivers in Boys, and even more impressive is the admirable economy of the streamlined screenplay whose oblique scenes all wind up snapping into place with the satisfying click of a puzzle coming together. Of a piece with Joko Anwar’s A Copy of My Mind, it’s another grounded movie about the secret forces that run the world, and how ordinary human decency is the only hope to defeat them.

In the Eighties and very early Nineties, filmmaking grants fueled the American independent scene, and thankfully this tradition hasn’t yet been stomped to death in Korea. One of Busan’s Asian Cinema Fund recipients is the digital Escher puzzle Alone, which goes full art-house but is still the most technically original movie of the fest. A filmmaker (Lee Ju-Won) snapping photos from his rooftop in a clotted Seoul neighborhood of winding alleys and narrow stairwells accidentally shoots a trio of masked thugs beating a woman to death on a nearby rooftop. Within seconds they’re banging on his apartment door and murdering him. Then he wakes up naked in the middle of the night in another part of the same neighborhood, menaced spookily by a weeping, incoherent woman and a little boy holding a sharp kitchen knife.

Anchored by stage actor Lee’s frantic performance and with only 37 cuts in its hour-and-a-half running time, Alone loves violating its own rules as it attempts to keep the audience off-balance, but unfortunately it winds up breaking so many of them that the weighty matters it wants to discuss wind up feeling weightless. However it’s so relentlessly creative—carrying over a repeated ringtone onto the swelling orchestral soundtrack, and positing a neighborhood with its familiar nooks and crannies as the swirls and loops of the human brain—that by the time the dying neighborhood shuts out all its streetlights one at a time, like the neurons in a human brain going dark, it’s more than earned its place as one of the most narratively bogus, but stylistically inventive, movies at BIFF.

4th Place

But it’s Jung Ji-Woo, one of Korea’s lesser-known new wave directors, who takes government funding and delivers the only masterpiece at this year’s BIFF with 4th Place. Conceived with and funded in part by the Korean Human Rights Commission, that imprimatur gives it the unfortunate stink of an ABC Afterschool Special, but this movie is not fucking around. Gwang-Su (Park Hae-Joon) is a one-time Korean swimming star who quit the Olympic team when his coach beat him one too many times and now, decades later, he’s a drunk, chain-smoking coach for Tiger Moms who want their elementary school kids bashed into swim-meet champions.

Jin-Ho (Yoo Jae-sang, scouted from an actual school swim team) is Gwang-Su’s latest victim, a 12-year-old space case whose mom is deranged by her fear that he’ll continue to come in fourth in swim meets and be doomed to a fourth-rate life. Jin-Ho has some natural talent, but his competitive edge only emerges when Gwang-Su beats him black and blue. The more he’s beaten, the better he swims, and Mom’s not about to question the results. Nor is Jin-Ho, who likes being a winner for once. But before it turns into 50 Shades of Swimming, Jung’s sharp eye for human self-deception and the unexpected beauty of commercial architecture give it a transcendental edge. It’s a movie about second chances and unfulfilled potential, made painfully poignant by the direction of Jung (whom many feel never lived up to the promise of his first film, Happy End, 99) and the performance of actor Park Hae-Joon (a respected stage actor who’s almost 40 and didn’t get his first leading role until this movie). Never didactic, this poisonous flower of a film says more about drive, ambition, and winning than anything else in Busan this year, but without a big name star in the lead or a famous director at the helm, it was largely lost in the shuffle—its failure to reach an audience a direct result of Busan’s overwhelming success at becoming an international festival.