Fear + Ana Mendieta

Sweating Blood

In 1997, security expert Gavin de Becker wrote The Gift of Fear: Survival Signals That Protect Us from Violence. Based on years of studying domestic abuse situations and threats to public figures, de Becker’s book advocates for trusting intuition: we have the ability to pick up on certain warning signs better than animals do, for we have the gift of foresight, but all too often they get rationalized away. To avoid being rude, we enter into a conversation with a creepy stranger we’d rather not talk to, or get onto an empty elevator with someone we don’t really want to be alone with. Michael Almereyda’s Experimenter, on Stanley Milgram and his obedience experiments, shows how natural initial responses can be repeatedly overridden by such irrational rationalizations.

The usefulness of fear came to mind recently while reading “Why Do We Teach Girls That It’s Cute to Be Scared?,” an article written by Caroline Paul, a former San Francisco firefighter. Mostly predicated on anecdote but peppered with a few social psychology studies, Paul’s piece argues that girls are socialized to be more afraid of hurting themselves (and of the world at large) than boys, which makes them “timid decision makers” when they grow up. At no point does she mention the threat of sexual violence or partner abuse, two pervasive problems that, consciously or not, very likely underpin a parent’s warning her daughter to be aware of her surroundings or cautious in certain situations. If we lived in a world where the only physical harm we could do to ourselves came from activities we elected to participate in—presumably a world where all men had successfully been taught not to rape and without any war—then this would hold more water. Unfortunately, there are still limits to treating girls the same way as boys.

Anima, Silueta de Cohetes

Paul’s argument sounds appealing, because it takes a stand against norms of female modesty that stop women from being decisive, and it reinforces a widely accepted understanding of gender equality. Yet the notion of women taking risks has obviously gone beyond well-intentioned cultural commentary and think pieces, in earlier social contexts when the stakes were much higher. Attending an exhibition of the works of Ana Mendieta, I was reminded of the especially subversive engagement with fear and physical harm running through much 1970s feminist performance art. Body art, an outgrowth of the loosely connected Viennese Actionist movement as well as happenings in the ’60s created by artists like Carolee Schneemann, used nudity and violence to critique war, objectification, and rape culture. Performances like Marina Abramović’s seminal Rhythm 0—in which the audience was invited to do to her whatever they wanted using a selection of 72 objects (which included a scalpel and a loaded gun)—revealed the extreme, grotesque treatment the audience would enact upon a female body unchecked.

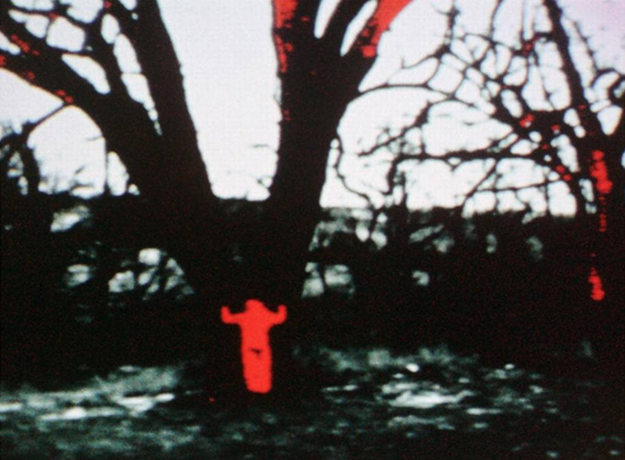

Mendieta, whose short films are now on display at Galerie Lelong through March 26, began developing her work during the same period. Known best for her performance art, Mendieta made over 100 shorts during her time at the University of Iowa, where she received two MFAs. More than simply documenting the performance pieces, Mendieta’s films are very much conceived as films, displaying an interest in camera placement, mise en scène, and editing that simply doesn’t exist in other recordings of performances from the era. Her early performances, such as Chicken Movie, Chicken Piece (72) in which she stands naked in front of an audience holding a slaughtered chicken as the blood drains out, were aggressive and confrontational, often referencing santeria religious practice of her native Cuba as well as menstruation. As this phase of her work progressed, her “action paintings” came to meditate on violence’s aftermath more than the act itself. Untitled (Blood Writing) “She Got Love” (74) shows Mendieta slowly painting a white wall with the words “she got love” in blood (or, more likely, red paint), lingering as they slowly drip down the wall. In Sweating Blood (73), in which blood slowly drips from her scalp, and Blood Sign (74), in which blood pours out of holes in a wall, the red fluid is separated from its automatic, vital function in circulation and instead becomes something arduous and effortful. Similarly, Untitled (Blood Sign #2/Body Tracks) (74) shows Mendieta standing in a yonic “Y” position, slowly smearing the walls with her outstretched arms, resulting in an outline of a labia. This “Y” pose would recur throughout her work, including her “siluetas,” outlines of her body formed from mounds of earth, traced into sand or dirt, or created from other objects—video effects in 1975’s Energy Charge, fireworks for 1976’s Anima, Silueta de Cohetes, and gunpowder in 1981’s Birth (Gunpowder Works). Energy Charge, like Butterfly (75), distorts and transforms her body into something unreal, yet ontologically present: using a 16-channel video processor to distort and color the image, her arms are obscured from the rest of her body, removing the boundaries between her and her surroundings. (In 1974’s Grass Breathing, she literally fuses her body with the earth by burying herself underneath a rectangle of sod, and the film documents her slowly heaving it up and down.)

Energy Charge

One of Mendieta’s most important cycles of work combines an investigation of violence, complicity, and voyeurism. In response to the rape and murder of University of Iowa nursing student Sara Otten, she created three pieces: with the first, Untitled (Rape Scene), Mendieta invited friends over to her apartment one night, and when they arrived the door was slightly ajar, and she laid naked and covered in blood across a chair, unresponsive; in Clinton Piece, Dead on Street, she laid in a pool of blood while another student photographed her; for Moffitt Building Piece (73), Mendieta poured animal blood and meat on a sidewalk and shot pedestrians’ reactions from within a parked car. While most people look away, a few stop to stare, one elderly woman even impaling a piece of meat on the tip of her umbrella. Her camera leers even if her subjects don’t, completely unaware of her presence. This pre-Mulvey exploration of the gaze is also evident in Door Piece (73). Shot through a keyhole, Mendieta’s body is broken up and abstracted; at times, you can make out various features (lips, cheek) when she sticks her tongue in. This provocative but playful move turns the keyhole into an orifice, taking control of it and making it about her own pleasure rather than the viewer’s.

In discussions of Mendieta’s work, three biographical details always come up, typically in the following order: her falling out of her Greenwich Village apartment window to her death in 1985 after a fight with her husband (who was acquitted of her murder); her family’s relocation to rural Iowa following Castro’s revolution in Cuba; and her affair and collaborations with Hans Breder, co-founder of the Intermedia Program at the University of Iowa. (It’s unfortunate that her untimely death, the most salacious tidbit, gets mentioned the most, but such tragic/romantic stories are beloved by the art market.) Her status as outsider—displaced by violence, a woman of color in a predominantly white state—is often used to explain her interest in observing extremes from a remove. Yet visiting the Galerie Lelong show and seeing several of her films that had not previously been exhibited, I saw clearly that they are also about confronting a certain type of feminine fear of the world. By incorporating her form into wild landscapes, by staging (or restaging) violent acts, by watching others watch, by using blood, her art challenges and triumphs over threats to physical safety, claiming the world as her own.